Dwight M. Morrow (R-NJ).

The Morrow Board’s final report is transcribed here in its entirety. These papers have been reproduced as originally written, with spelling corrections and editorial additions highlighted and bracketed in blue. If you find any errors in my transcription, please do not hesitate to contact me.

Report of President’s Aircraft Board

NOVEMBER 30, 1925

GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE

WASHINGTON

1925

The PRESIDENT :

We have the honor to submit the following report :

THE APPOINTMENT OF THE BOARD

Your letter addressed to Hon. Curtis D. Wilbur, Secretary of the Navy, and Hon. Dwight F . Davis, then Acting Secretary of War, indicates the purpose of the appointment of the board:

THE WHITE HOUSE ,

Washington, September 12, 1925.

GENTLEMEN: Your joint letter stating that “For the purpose of making a study of the best means of developing and applying aircraft in national defense and to supplement the studies already made by the War and Navy Departments on that subject, we respectfully suggest that you as commander of chief of both Army and Navy appoint a board to further study and advise on this subject” has just been received. Your suggestion is one which already had my approval so far that last spring I had conferred with parties as to the desirability of taking such action, so that a report might be laid before me for my information and also for the use of the incoming Congress. I am therefore asking the following-named gentlemen to meet me at the White House on Thursday next at 11 o’clock in the forenoon, when I shall suggest to them that they organize by selecting their own chairman and proceed immediately to a consideration of the problem involved, so that they can report by the latter part of November:

Maj. Gen. James G. Harbord, retired, of New York City.

Rear Admiral Frank F . Fletcher, retired, of Washington, D. C.

Mr. Dwight W. Morrow, of Englewood, N. J., lawyer and banker.

Mr. Howard E. Coffin, of Detroit, consulting engineer and expert in aeronautics.

Col. Hiram Bingham, of New Haven, Conn., Senator, formerly in the Air Service and member of the Senate Committee on Military Affairs.

Hon. Carl Vinson, of Milledgeville, Ga., member of the House Committee on Naval Affairs.

Hon. James S. Parker, of Salem, N.Y., chairman of the House Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce.

Hon. Arthur C. Denison, of Grand Rapids, Mich., judge of the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals.

Mr. William F. Durand, of Stanford University, California, president of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers, member of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics.

Very truly yours,

CALVIN COOLIDGE.

Hon. CURTIS D. WILBUR,

Secretary of the Navy.

Hon. DWIGHT F. DAVIS,

Acting Secretary of War. 71066 — 2541

-1-

The letter of appointment addressed to each of the nine members of the board, [enclosing] copy of the foregoing communication, is as follows:

THE WHITE HOUSE,

Washington, September 12, 1925.

MY DEAR MR. ______: [Enclosed] is a copy of a communication which you may have seen in the press. I request that you serve in the capacity indicated, and I would like you to meet me at the White House on Thursday, September 17, at 11 o’clock in the forenoon, and lunch with me at 1 o’clock. I feel that your efforts will result in bringing out the good qualities of the Air Service and in suggesting what action can be taken for their improvement.

Very truly yours ,

CALVIN COOLIDGE.

We held our first meeting Thursday, September 17, and organized by the election of Dwight W. Morrow as chairman, Arthur C. Denison as vice chairman, and William F. Durand as secretary.

THE EVIDENCE AVAILABLE TO THE BOARD

Thereafter we held public hearings for four weeks, having before us in person 99 witnesses, of whom more than half were actual flying men. We designedly [sic] gave the greater portion of the time to hearing those men who had actual air experience. This seemed desirable because there has been a widespread impression among flying men that their point of view and professional opinions have not been enough considered, that large matters of policy have been determined by men without flying experience. Through the hearty cooperation of the War and Navy Departments we were able to make clear to the flying men that the opinions desired of them were their personal opinions, whether or no those opinions coincided with the opinions of the departments.

In addition to the flying men, we have heard from the Secretary of War, the Secretary of the Navy, the Postmaster General, and the Secretary of Commerce, as well as from their technical advisers and the heads of their bureaus and departments. We have heard representatives of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics. We have heard the chairman of the Appropriations Committee of the House of Representatives. We have heard the leaders of the aircraft industry. Further, we have had the advantage of the testimony heard by the Committee on Military Affairs of the House of Representatives on H. R. 10147 known as the Curry Bill and the testimony taken by the select committee of the House of Representatives, Sixty-eighth Congress, known as the Lampert Committee. At the time of preparing this report this last-named committee has not yet reported. Through the courtesy of the committee, however, the printed record of its testimony has been made fully available to us. We have also had the opportunity of examin-

-2-

ing the testimony taken in various other hearings before congressional committees, and likewise the published reports of other governments upon their aircraft problems and the numerous studies that have been made by private organizations in this and other countries.

We have kept steadily in mind the mission which you gave us. We are not primarily concerned with questions of Army discipline. These are problems with which armies always have had to deal and always will have to deal. They must be dealt with through the ordinary channels. They do not fundamentally affect the problem upon which you have asked us to report.

THE CONFLICT IN THE TESTIMONY

The one thing that stands out clearly at the very outset of a consideration of the problem is the great conflict in the testimony. This conflict extends not only to matters of opinion, where it is necessarily to be expected — indeed, where to some extent it is to be desired — but also to what seem to be differences in statement of fact. There are some real conflicts on questions of fact. In most cases, however, the apparent differences in fact are merely different conclusions resulting from partial statements of fact.

There is apparently a wide divergence of opinion as to the number of usable airplanes under the control of the United States Army and Navy; as to the number of airplanes in use by other first class powers; as to the effect of bombing and of antiaircraft fire; as to the physical possibilities of aircraft in carrying bombs and the distance they can be carried; as to the extent of the civilian use of aircraft here and abroad; as to the extent of industrial preparedness here and abroad. We are told that the United States Army has available for use 1,396 good airplanes, and that it has available for use only 34 good airplanes; that America stands far behind Japan in number of airplanes, and that Japan stands far behind America in number of airplanes; that anti-aircraft fire has no effect upon air attack, and that anti-aircraft fire is one of the greatest menaces to air attack; that the United States is at the present time open to air attack from overseas from all sides, and that the distance from which an effective air attack can be launched is not more than 200 miles; that the air mail service between Chicago and New York does not yet commercially pay, and that an air service between New York and Peking should be established and that the saving in the transportation of commercial paper alone would pay its expenses from the beginning.

AVIATION BEFORE THE WAR

In all this confusion of opinion one fact stands out clearly. During the past generation a great new factor has come into men’s lives. Men have learned to fly. They are still subject, of course, to

-3-

the laws of gravity; but they have learned to rise from the ground in heavier-than-air machines, to propel themselves above the ground, to control with skill their speed and direction, and to carry substantial weights with them. This has all happened within a little more than 20 years. On December 17, 1903, Orville Wright flew a power-driven airplane at Kitty Hawk, N.C. The world did not appreciate what had happened. During the next few years, until the outbreak of the World War, there was steady progress in aircraft accomplishment, based largely on the development of the light gasoline engine. Progress in Europe was greater than in America despite the fact that the airplane had come from this country. This may be attributed in part at least to the greater pressure upon European countries during those years to prepare for war. Apart from the possible war use, however, airplanes were largely the playthings of inventors or of sportsmen.

THE IMPETUS THAT THE WAR GAVE TO FLYING

With the outbreak of the World War there was removed from aircraft development one of the great limiting factors, to wit, the question of expense. No cost was too great for anything that might contribute to the winning of the war. In all the European nations the governments turned their attention to the use of aircraft. When the United States entered the war in 1917 a great deal of this European development was unknown to us. All of it had to be assimilated rapidly. Like the other countries of the world, the primary purpose of the United States, of course, was to develop as quickly as possible such air power as might contribute to the shortening of the war. A colossal effort was made, and a colossal industrial machine created from practically nothing. More than 16,000 airplanes, with motors, were delivered by American manufacturers. In addition approximately 25,000 motors were produced and at the time of the armistice were being provided at the rate of 4,000 per month. Competent authorities believe that by March, 1919, the country could have been producing 10,000 Liberty motors a month. In aircraft, as in many other lines of America’s endeavor, things that were gotten ready for possible campaigns in 1919 and 1920 were fortunately not needed. How much that unused preparation contributed to the shortening of the war no one can tell.

THE CONTROVERSY THAT HAS GONE ON SINCE THE WAR

With the coming of the armistice, the United States began to liquidate a vast war machine, at the same time endeavoring to retain and further extend the scientific and technical knowledge which the war experience had brought. The severe liquidation brought a violent

-4-

wrench to all industries, including those furnishing aircraft. More over, the reduced army of peace meant reduction in rank and curtailment of opportunity for all officers in the Army. It is not unnatural that the controversy, which arose between the newer and the older arms of that service should have raged with some bitterness. Various causes have been assigned for that controversy — the prejudice of the older arms of the service against the new arm, the lack of discipline of the new arm, the fact that the casualties in the new arm are much greater than in any other arm of the service, the sensational character of the airman’ s work even without exaggeration, the readiness with which that work may be exploited by those seeking sensation, the violent propaganda of interested parties. Any and all of these causes have been put forward. It is impossible to attribute the controversy to any single cause, particularly in view of the fact that it has gone on in much the same terms in every country that participated in the war. The conflict is one between the old and the new, emphasized by the sharp adjustments required in a period immediately following a great war. Such conflicts of thought have gone on from the beginning. They will go on until the end. It is in many ways desirable that they should go on, even in armies, subject always, of course, to that essential discipline without which an army becomes a mob. What is needed is a more generous appreciation by each side of the difficulties of the other side. On each side there is need of patience with what seems the unreasonableness of the other side. The fundamental problem may not be settled. It may, however, be understood if men will approach it with less feeling and more intelligence.

METHOD OF APPROACH

In taking up the actual problems with which our study has been concerned it has seemed to us useful to divide our report into two parts. In Part One we put forward a series of questions covering some matters in controversy, which, despite the conflict in testimony, admit of answers. Having answered such questions as the evidence before us requires, we then consider in Part Two some positive action that we think should be taken to improve the Air Services — I, with reference to the Army; II, with reference to the Navy; and III, with reference to industry as the source of supply for aeronautic materiel.

In suggesting remedies we rest upon the sound principle that no solution proposed at this time can be lasting. It is, therefore, of the first importance to lay the emphasis upon the best method of achieving the desired result. To that end we rely chiefly upon the appointment of an additional Assistant Secretary of War, Assistant

-5-

Secretary of the Navy, and Assistant Secretary of Commerce, to devote themselves under the direction of their respective heads, primarily to aviation and jointly to coordinate so far as may be practicable the activities of their three departments with respect to aviation.

PART ONE

The questions to which we attempt answers are as follows:

First. In determining an aviation policy for the United States Government, what should be the relation between the military and civilian services ?

Our answer to this question is that they should remain distinctly separate.

The historic tradition of the United States is to maintain military forces only for defense and to keep those forces subordinate to the civilian government. This policy has been amply justified by our experience. It has been proposed that we should establish a Department of Aeronautics, which should control all or a portion of our military air power as well as our civilian air activities. Such a departure would be quite contrary to the principles under which this country has attained its present moral and material power. If the civilian air development should have anything like the wide ramifications that are predicted for it, such a new policy might have a profound effect upon the historic attitude of our Nation toward military and civilian activities. The peace-time activities of the United States have never been governed by military considerations. To organize its peace-time activities, or what it is thought may ultimately be one large branch of them, under military control or on a military basis would be to make the same mistake which, properly or improperly, the world believes Prussia to have made in the last generation. The union of civil and military air activities would breed distrust in every region to which our commercial aviation sought extension.

Nor do we see any force in the argument that the building up of a large air power — partly military and partly civilian — would be a peace movement. In the Conference on the Limitation of Naval Armaments [Washington Naval Treaty] the nations which took part made a real sacrifice of weapons which they believed to be effective. There was a real effort to secure peace by relying upon mutual agreements and good faith. Those who believe in the preponderating effect of air power, however, are not talking of disarmament when they suggest the sacrifice of battleships. They are talking of discarding the weapon which they think is becoming useless and substituting therefore what they believe to be a more deadly one. Whole cities are to be quickly demolished and their inhabitants destroyed by high explosives and

-6-

poisonous gases. The argument is thus stated: “The influence of air power on the ability of one nation to impress its will on another in an armed contest will be decisive. ” Wars against high-spirited peoples never will be ended by sudden attacks upon important nerve centers such as manufacturing plants, depots, lighting and power plants, and railway centers. The last war taught us again that man can not make a machine stronger than the spirit of man. The real road to peace rests not upon more elaborate preparations to impress wills but rather upon a more earnest disposition to accommodate wills.

By our fortunate geographical position we have heretofore been freed from the heavy burden of armament which necessity seems to have imposed upon the nations on the Continent of Europe. If one thing has stood out sharply in the past century it has been the great danger of the defensive movements of a nation being interpreted by their neighbors as offensive movements. This has naturally, perhaps inevitably, thrown most of the countries within the European orbit into the vicious circle of competitive armaments. We are all in accord that the United States must at all times maintain an adequate defensive system, whether it be surface ships, submarines, land armies, or air power. But let us not deceive ourselves. This new weapon, with its long range of power not only for defense but also for offense, is subject to the psychological rules which govern all armament. Armaments beget armaments. It has been our national policy heretofore to oppose competitive armaments. The coming of a new and deadlier weapon must not result in any change in this policy. The belief that new and deadlier weapons will shorten future wars and prevent vast expenditures of lives and resources is a dangerous one which, if accepted, might well lead to a readier acceptance of war as the solution of international difficulties. The arrival of new weapons operating in an element hitherto unavailable to mankind will not necessarily change the ultimate character of war. The next war may well start in the air but in all probability will wind up, as the last war did, in the mud.

Second. How can the civilian use of aircraft be promoted?

This brings us directly to the part of our inquiry which has perhaps attracted the least popular attention but which may well be the most important question which aviation presents in its far reaching consequences to our people.

The rapid development of aircraft under the impetus of the war has not unnaturally led to the strange assumption in many people’s minds that this new conquest of science is to be dedicated mainly to war purposes. No witness who appeared before your board made a more striking impression than the modest gentleman from Dayton,

-7-

Ohio, who, with his brother, more than 20 years ago, started men flying. We can not refrain from quoting to you the words with which Orville Wright began his testimony:

Not being a student of naval or military affairs, I shall not presume to make any suggestions as to the use of aircraft in warfare. I offer only a few suggestions, and none of them new, along the lines of civil aviation, in which I believe the National Government can and should take part immediately.

A great opportunity lies before the United States. We have natural resources, industrial organizations, and long distances free from customs barriers. We may, if we will, take the lead in the world in extending civil aviation. In this field international competition is to be desired by all.

Progress in civil aviation is to be desired of and for itself. Moreover, aside from the direct benefits which such progress may be expected to bring us in our peace-time life, commercial aeronautic activity can be of real importance in its effect on national defense. It creates a reservoir of highly skilled pilots and ground personnel. Whatever is done to increase the use of aircraft, to spread familiarity with aircraft among the people, and in general to develop “air mindedness” will make it easier rapidly to build up an expanded air power if an emergency arises.

Both here and abroad, great strides have been made in the commercial use of the airplane in the last four years. In the United States, during the fiscal year 1925, the air mail flew a total distance of 2,501,555 miles, and it is unique among the world’s air lines that much of its regular flying is done at night. While no single European country shows as large a total as that for civilian operation, the total for all of Europe during 1924 is almost exactly 6,000,000 miles, with 64,000 passengers and 2,500 tons of mail and express carried.

There has been no more inspiring chapter in American enterprise and courage than the establishment and conduct of the United States air mail. As early as 1918 the Post Office Department initiated the air mail with a route from New York to Washington. The saving in time was not sufficient to justify the continuance of this route. Other short routes were tried and abandoned for the same reason. Since July 1, 1924 , the air mail has been operating a through service from New York to San Francisco. Since July 1, 1925, there has been in operation an additional service by night between New York and Chicago. There is now a lighted airway from New York to Rock Springs, [Wyoming]. The Post Office Department owns 96 airplanes, of which 61 are equipped for night flying. Beacon lights guide the night pilot along the routes. In addition to the regular landing fields there are emergency landing fields and a system of

-8-

revolving lights with red danger signals which enable the ground operator to signal to the pilot regarding weather conditions. The Post Office Air Mail Service has grown from 21,389 miles flown in the fiscal year ending June 30, 1918, to 2,501,555 miles flown in the fiscal year ending June 30, 1925. The total miles flown since the establishment of the air mail amounts, to the end of the last fiscal year, to 10,526,532 miles. The service is not free from danger, but owing to the regularity of the route and the rigid inspection of the airplanes there has been a gratifying decrease in accidents.

In addition to the Air Mail Service there has been in this country some further development in the use of aircraft for civil purposes, such as crop dusting, aerial photography, forest patrol, timber cruising, and private operation for personal transport.

As common carriers, however, aircraft have not been used as much in this country as in Europe. In this respect they should stand on a general parity with vehicles of transportation by sea. For waterborne transport the Federal Government has provided a body of marine law. It lights the coasts, harbors, and rivers; it studies the currents and marks the channels; it surveys all navigable waters and publishes charts, sailing directions, and the Nautical Almanac; it maintains the Life Saving Service, regulates anchorages, issues weather maps and storm warnings, and spends millions yearly on river and harbor improvements; it inspects and certifies vessels for seaworthiness and examines and licenses all officers. If these aids were withdrawn waterborne transport would be difficult, if not impossible, under modern economic conditions. Unless some similar aid be given to air transport development in that line will be seriously retarded.

The principal conditions standing in the way of progress and acting in restraint of the more rapid investment of private capital in the field of air transport are :

(1) The excessive burden placed upon private capital if it is to be required to pioneer in the development of flying equipment best suited to air transport and at the same time supply all the collateral requirements including airways and air navigation facilities, especially as such facilities are, by their very nature, open to the use of all, and no proprietary rights can be retained by the parties undertaking the original investment and the expense of maintenance. The parallel with maritime transport in this particular is exact.

(2) A fear of the hazards of the air which makes it difficult to secure passengers, and a general idea of the airplane as a military or sport vehicle, unreliable for other use.

(3) A general uncertainty on the part of potential operators regarding the extent of the traffic available.

-9-

(4) The lack of a definite legal status and of a body of basic air laws.

(5) The absence of Government inspection and certification of flying equipment and licensing of pilots, and the lack of control over methods of maintenance and operation in so far as they have a direct bearing on safety.

(6) The slowness of the development of insurance facilities.

To the end that this important field should receive the attention that it deserves, we recommend that provision be made for a Bureau of Air Navigation under an additional Assistant Secretary of Commerce. We recommend the progressive extension of the air mail service, preferably by contract, and also that steps be taken to meet the manifest need for airways and air-navigation facilities, including an adequate weather service maintained by public authority and planned with special reference to the needs of air commerce.

Beyond these general recommendations, we do not presume to suggest the definite legislation which should be passed upon this subject. Congress has already considered it at length. The Department of Commerce has made elaborate studies. We trust that the necessary legislation and appropriations can be made effective in the very near future and a start made in this vitally important field.

Third. What should be the military air policy of the United States?

Any consideration of the air policy of the United States, especially as regards the military air strength which we should develop, with its influence on the National Budget, should be based on a careful consideration of

(1) The general military policy of the United States,

(2) The air strength of those foreign States which, having in view our geographical position, could menace our security.

Our naval strength is now determined by international agreement. So far as naval warfare is concerned, the strengths of the air arms of the naval forces of world powers will presumably be in close relation to the naval strengths authorized under the convention regarding the limitation of armaments. Here our obvious general policy should be to maintain our naval aviation in due relation to the fleet.

Our national policy calls for the establishment of the air strength of our Army primarily as an agency of defense. Protected, as the United States is, by broad oceans from possible enemies, the evidence submitted in our hearings gives complete ground for the conclusion that there is no present reason for apprehension of any invasion from overseas directly by way of the air; nor indeed is there any apparent probability of such an invasion in any future which can be foreseen.

It furthermore appears that in order to place any considerable enemy air force in a position for effective operation against our

-10-

cities, ground armies, or military positions, it would be necessary to transport such force by waterborne shipping — airplane carriers and cargo ships — and establish a land base from which such operations could be carried on. This could not be effected so long as our fleet is undefeated on the sea.

A careful study by the Army and Navy high commands of the factors entering into the question of the air strength, should indicate the total strength needed in order to insure the proper measure of national security, while at the same time holding a consistent relation to our traditional policy of maintaining armed forces for defense rather than for aggression, and to the need of wise economy in all demands on the public purse.

Due to the special prominence which it has received through news paper publicity and otherwise, it seems well to supplement the reference in the preceding question regarding our danger from overseas attack by way of the air, by some more specific discussion of the following question:

Fourth. Is the United States in danger by air attack from any potential enemy of menacing strength?

Our answer to this question is no.

This conclusion is based on the facts as they now are. No airplane capable of making a transoceanic flight to our country with a useful military load and of returning to safety is now in existence. Airplanes of special construction and in special circumstances have made nonstop flights over land of 2,520 [LT John A. Macready and LT Oakley G. Kelly, piloting a Fokker T-2 over Dayton, OH, 17 April 1923] and 2,730 miles [Maurice Drouhin and Jules Landry, piloting a Farman F.62 over Chartes, France, 9 August 1925]. Neither of the airplanes which made these flights carried any military load. Both flights were made under as nearly ideal weather conditions as possible, the purpose being record-breaking performances. The mere fact of the distance covered in these flights is, therefore, no criterion of the ability of airplanes to make transoceanic flights of equal distance under war conditions and with an effective military load. Although there is some variance in the testimony on this point it seems to be the consensus of expert opinion that the effective radius of flight for bombing operations is at present between 200 and 300 miles. By effective radius of flight of a bombing airplane is meant the distance from point of departure to an objective which this airplane could bomb and then return to its starting point. This distance, for large bombing operations, includes allowance for possible adverse weather conditions, for the capacity of personnel as contrasted with the capacity of the airplane itself, for some reduction in speed and range in the case of a squadron as compared with a single plane, and for time lost over the objective. All of this results in a very considerable reduction in radius for effective operation as compared with that which might be based on a single trial flight under favorable conditions. With the advance in the art it is

-11-

to be expected that there will be substantial advance in the range and capacity of bombing airplanes; but, having in view present practical limitations, it does not appear that there is any ground for anticipation of such development to a point which would constitute a direct menace to the United States in any future which scientific thought can now foresee.

Commander Rodgers, in command of the PN 9 on the recent flight to Hawaii [CDR John Rogers, whose flight was lost for nine days after ditching on 1 September 1925], states that there is no airplane in existence which would be able to come to this country across either ocean carrying a heavy military load, nor is the construction of one to be expected with known materials and known motive power. Commander Towers, one of the oldest flyers in the Navy, who participated in the flight in 1919 from Newfoundland to the Azores [CDR John H. Towers participated in the 1919 transAtlantic flight piloting one of the two aircraft (NC-3) which failed to complete the crossing], expresses the opinion that for either of our coasts to be bombarded from overseas would involve transporting airplanes by surface craft across the ocean. He adds that “with opposition it would be entirely ridiculous.”

The fear of such an attack is without reason.

In the foregoing we are speaking of an attack upon the continental United States, and are ignoring an attack from Mexico or Canada. To create a defense system based upon a hypothetical air attack from Canada, Mexico, or any other of our near neighbors would be wholly unreasonable. For a century we have, under treaty [Rush-Bagot Treaty, 28 April 1818], left the Great Lakes unguarded by a naval force; by mutual consent the long Canadian frontier is free from armament on either side. The result has justified such a course.

Fifth. Should there be a department of national defense under which should be grouped all the military defensive organizations of the Government?

We have, at an earlier point, considered a separate department of the air under which it has been proposed there should be grouped both military and civilian aviation activities. Such a proposition we have disapproved for the reason that civilian and military activities should, in our opinion, be kept separate. The present question involves different considerations. It is, in fact, largely a question of administrative machinery. Entirely apart from the problems that have been raised by the new and enlarged uses of military aviation, the question has been often before considered of uniting the Army and the Navy under a Secretary of National Defense. President Harding [Pres. Warren G. Harding (R-OH)] made such a proposal to Congress, but so far as we have been able to discover, this proposal did not meet with favor either in Congress or in the Army and the Navy.

The argument in favor of such a course has been and is that there is now overlapping of the Army and Navy. There is some strength in the argument. Such consolidation might secure more cooperative training in times of peace and perhaps some economies in buy-

-12-

ing. The amount of overlapping is, however, less than is generally assumed. Moreover, an element of competition in certain matters has its advantages.

The argument against such a course is the added complexity in organization which would inevitably result. The Army and Navy organizations urge with force that each of them is entitled to a member of the Cabinet in order that its special views may be properly presented to the President and to the Congress. If the two present service organizations were consolidated under a single secretary it would at once become necessary to create a super general staff. No secretary of national defense could operate the two organizations without subsecretaries and technical advisers. This supergeneral staff, which would be in addition to the present service staffs, would necessarily comprise Army and Navy advisers who had been educated not only in their own particular schools but who would be required to have taken courses in the schools of the service to which they did not belong. It is difficult to see how any such super-organization would make for economy in time of peace or efficiency in time of war.

During a war period the President as the Commander in Chief of both services must act as the director of national defense. President Lincoln [Pres. Abraham Lincoln (R-IL)] in the Civil War [American Civil War (1861-1865)] and President Wilson [Pres. T. Woodrow Wilson (D-NJ)] in the World War [The Great War (1914-1918)] had to assume such a position. Moreover, when the President assumes such a position the necessity of linking the defensive agencies of the Government does not stop with the Army and the Navy. The Council of National Defense, which during the World War was organized to coordinate our industries and resources, included the Secretaries of War, Navy, Interior, Agriculture, Commerce, and Labor. There are thus swept into the actual department of national defense, acting under the President many other organizations whose activities during peace time have nothing directly to do with defense. The memory of the Great War is so recent that we hardly need call attention to the fact that rail roads, coal supply, agricultural activities, important war industries, dealings with labor, all by special legislation had to be brought into coordination with the work of the Army and the Navy.

We do not recommend a Department of National Defense, either as comprising the Army and the Navy or as comprising three coordinate departments of Army, Navy, and Air. The disadvantages outweigh the advantages.

Sixth. Should there be formed a separate department for air, coordinate with the present Departments of War and Navy?

Our answer is no.

The quoted opinion of General Pershing [GAS John J. Pershing, former CG AEF] and the direct testimony of General Summerall [CG US II Corps MG Charles P. Summerall], General Hines [CSA MG John L. Hines], and General Ely [Commandant US Army War College MG Hason E. Ely], of Admiral

-13-

Sims [RADM William S. Sims, former CO US Naval Forces Operating in European Waters], Admiral Eberle [CNO ADM Edward W. Eberle], Admiral Robison [CO US Fleet ADM Samuel S. Robison], Admiral Coontz [CO Fifth Naval District RADM Robert E. Coontz], and Admiral Hughes [CO US Battle Fleet ADM Charles F. Hughes] stressed the need of the Army and of the Navy for their own air services. Modern military and naval operations can not be effectively conducted without such services acting as integral parts of a single command. Moreover, the training of these air services that are to act with the Army and with the Navy must be under the continuous direction and control of the command which is ultimately to use them. In these conclusions and principles we concur. The question left to consider is whether the country has need of a separate independent air force in addition to the air power required for use with the Army and the Navy. We do not consider that air power, as an arm of the national defense, has yet demonstrated its value — certainly not in a country situated as ours — for independent operations of such a character as to justify the organization of a separate department. We believe that such independent missions as it is capable of can be better carried out under the high command of the Army or Navy, as the case may be.

The example of the British Air Ministry, in complete control of all of Britain’s aeronautic activities, is frequently cited by those who urge the organization of an air department in our Government. Because of our different geographical position we attach no weight to this precedent. In this connection we desire to draw attention to the fact that in Great Britain itself there is no unanimity of expert opinion as to the ultimate value of the Air Ministry from the viewpoint of national defense. We pass over the British newspaper comment that has been submitted to us. Statements both for and against can be found. The fact remains that between the close of the war and the beginning of 1923 Britain was agitated by an almost continuous discussion of the merits and demerits of the Air Ministry. The result was the appointment by the Prime Minister [PM the Rt. Hon. Stanley Baldwin (CP)], in March, 1923, of a subcommittee of the Committee on Imperial Defense to inquire into the cooperation and correlation of the Army, Navy, and Air Force in matters of national and imperial defense [Salisbury Committee (Lord James E. H. Gascoyne-Cecil, chair)]. This subcommittee reported on November 15, 1923. Incorporated in the main report was a special report dealing particularly with the relations of the Navy and the Air Force. The committee heard “a great deal of evidence from witnesses from both departments” [Navy and Air Force]. None of this evidence, however, has been made available to us. The report refers to the controversy between these two services as “somewhat acute.” The Air Ministry “strongly objected to being partially dismembered so soon after it had been brought into existence.” To the Admiralty, on the other hand, it seemed “intolerable” that they should be responsible for the success of the Battle Fleet and not have control of their own air arm. The result was to continue the separate Air

-14-

Ministry but to give the Admiralty a greater measure of control of the fleet air arm. Those who assert that Great Britain is about to repudiate her independent Air Ministry go beyond the known facts. Those who say that the matter is finally settled by this report likewise go beyond the known facts.

PART TWO

Having answered the foregoing questions as the evidence before us requires , we shall now consider some positive action that we think should be taken to improve the air services, (I) with reference to the Army, (II) with reference to the Navy, and (III) with reference to the industry as the source of supply for aeronautic matériel.

I. THE ARMY

Our consideration of the Army Air Service can be conveniently treated under three headings, first, its strength; second, its condition in respect of personnel and matériel and the criticisms thereof; third, recommendations for its improvement .

The Army Air Service is a branch of the Army — which in its general status is similar to other major branches of the Army, such as Artillery, Infantry, and Cavalry. It has in general the same degree of independence and is subject to the same degree of supervision and control under the Secretary of War and the War Department General Staff as the other branches. It has two major functions — one to render service in an auxiliary role in time of war to other combatant branches of the Army and the other that of an air force acting alone on a separate mission.

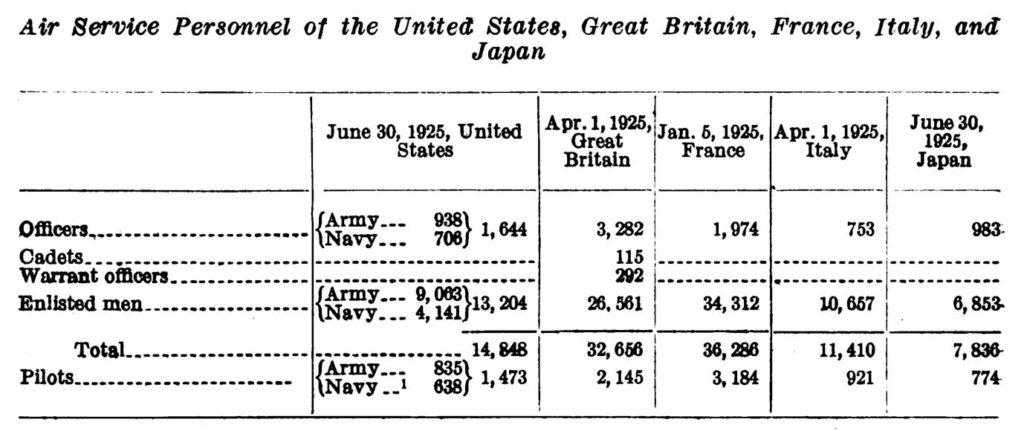

Its present authorized strength is 1,247 officers and 8,760 enlisted men out of a total authorized strength for the entire Military Establishment of 12,000 officers and 124,988 men. The actual strength on June 30, the close of the last fiscal year, was 912 officers and 8,722 men, at which time the actual strength of the whole Army, including the Air Service, was 11,647 officers and 115,130 men.

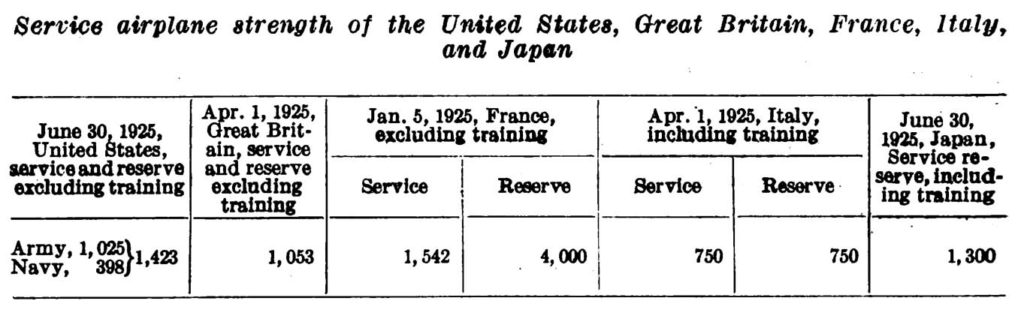

In assessing the matériel strength of the Air Service the board has encountered much difficulty, particularly in attempting to compare this strength with that of the other principal military powers.

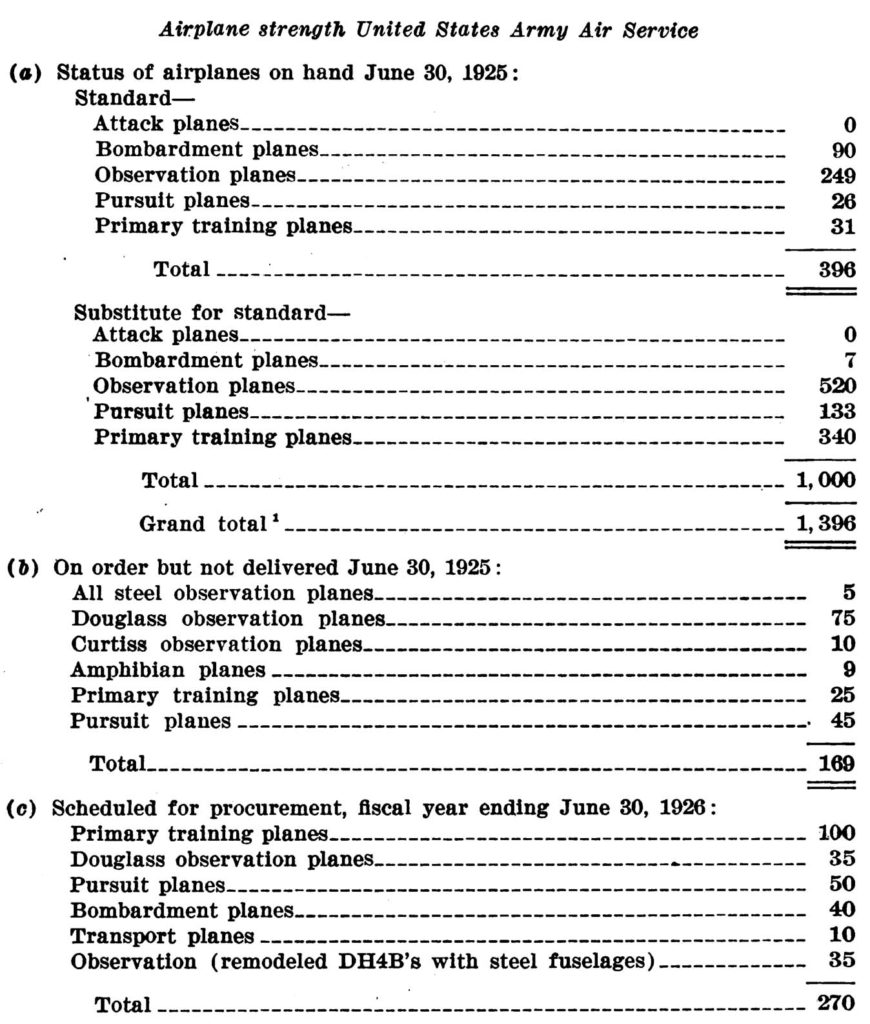

Regarding the strength of our own service, the most authoritative figures placed before us are those of General Patrick, the Chief of the Army Air Service [CG USAAS MG Mason M. Patrick], in which he defined “standard” planes as those “that could be used in emergency or if we suddenly went to war.” Under this definition he places our strength on June 30 last, at 396 standard planes. He also states that there were on June 30 last in commission or in reserve an additional 1,000 “of a similar type but of less value — but planes that might be used in war times.”

-15-

He further has stated that since June 30 last there have been received or are on order or are covered by present purchase plans for the Air Service 439 additional standard planes. The details of these figures by types and also a comparison of numbers of airplanes with foreign powers is given in Appendix A.

The air strength of any particular power should be considered in relation to its anticipated value in the scheme of national defense of that power and in relation, likewise, to the remainder of the military establishment. France, for example, has an army more than five times as large as our own, while the army of the British Empire is more than twice our own. Our strength of air arm in proportion to general military establishment compares favorably with that of any other power. Geographical position with reference to other nations is bound to affect necessary air strength as it affects the rest of the Army.

We turn to the second consideration that is, the condition of personnel and matériel in the Air Service and the criticisms thereof.

We have found cause for nothing but praise of the skill, daring, and individual accomplishments of our Army air pilots. They may challenge comparison with any in the world. Evidence before us has shown that much time and attention have been devoted to the study of air strategy, the development of air tactics, the design and construction of the very latest types of planes, and of all auxiliaries such as bombs, bomb sights, aircraft armament, photographic and other special equipment, and to the system of inspection to insure safety.

If we have found difficulty in arriving at fair bases of comparison in dealing with figures of strength, it is even more difficult to assess our exact place in comparison with other powers in the more intangible fields of military and technical development. It must be recognized, however, that our military and naval Air Services hold a major share of the world’s air records. The round- the-world flight was made by American Army pilots [Four Douglas DTs commanded by MAJ Frederick Martin and LT Lowell H. Smith, 6 April 1924 – 28 September 1924]. Other notable feats have been at least as numerous in our services as in those of other powers. The quality of our personnel and of our equipment in general can safely face comparison with that of any other power.

It must be recognized that our Army Air Service personnel has been subjected in the years since the war to an extremely difficult and trying ordeal. The general effects of the reduction of the Army after the world-wide war endeavor have been traced in an earlier section of this report. The effect of the violent change from war to peace conditions, involving as it did great reductions in rank, was a difficult ordeal for all branches of the service, and particularly so for the newest branch, which as an arm had little experience of peace conditions.

-16-

One effect of these readjustments has been to create a feeling of unrest and dissatisfaction and of impatience against the control of the War Department General Staff. These feelings have been aggravated by questions of rank and promotion, resentment of control by non-flying officers, shortage of officers of flying experience in the higher grades, apprehension of wholesale transfers to the Air Service of senior officers from other branches of the Army, and dissatisfaction with the single promotion list.

We do not believe that the release of the Air Service from the same degree of control by the General Staff as that imposed on other coordinate branches of the Army is justified. Such a move would strike at the basic principle of unity of command and would depart from the organization of the Army created by Congress in 1903 [the Militia Act of 1903, an act which placed state militias under federal control – i.e., the National Guard], developed and perfected through 17 years of peace and war, and again revised by Congress in the national defense act of 1920. These changes in organization first established and then strengthened the General Staff, whose business is to exercise supervision over training, discipline, and inspections, to formulate policies, and to advise the Secretary of War. It does not administer. Its chief duties are concerned with preparation for war.

There will be found at the end of this section of the report recommendations regarding changes in the handling of Air Service personnel, which we believe should go far to allay many of the causes of criticism briefly reviewed above.

Turning now from personnel to matériel, there is found among the criticisms adduced in evidence before us the recurrence of the terms “obsolete,” “obsolescent,” and “unsafe.”

The question of when an airplane for military purposes becomes “obsolete” is entirely a matter of judgment. In appraising the judgment exercised on this question two points must be kept in mind. First, that in a national emergency until the industry has been mobilized on a large production basis, every existing airplane which is safe, regardless of age and type, will probably be used for some military purpose; and second, that the useful life of a plane in active military service even in time of peace is very limited.

The term “obsolescent” may be applied to any type of plane as well as to any type of automobile as soon as it has been put in service. By such time a new and better model is likely to be in the stage of design or development. This is a condition of progress and is especially notable in a new and fast developing science or art such as aviation.

The rapidity of development in the new science must of necessity in any country result in there being but a small proportion of

-17-

absolutely new and up- to-date planes out of the total possessed by any service.

The fact that any plane is “obsolete” or “obsolescent” does not necessarily mean that it is “unsafe.” Lack of safety may result from faulty aerodynamic or general design, from structural weakness, from unreliability of power plant, or from deterioration through use or age. We find no evidence tending to show basically faulty aerodynamic design, or lack of structural strength as dependent upon design or construction. Nor unreliability of American airplane engines as compared with those of foreign design and manufacture.

The safety of planes, in so far as their deterioration through use or age is concerned, is dependent on rules and regulations for inspection and operation, and their strict enforcement. General Patrick stated before us on October 13 that “the planes we have in service are inspected most rigidly before they are taken into the air. No man is allowed to take into the air a plane that is regarded in any way as unsafe.” Casualties have occurred. Moreover, with the art of military flying depending as it does, so largely on elements of physical condition, training, skill, and judgment on the part of the pilot, casualties will occur, no matter what the equipment or how careful the inspection. The records show that the accident rate per number of miles flown has been steadily decreasing and that it compares favorably with the accident rate in other air services.

In particular, much criticism has been directed against the DH plane [Airco DH.4, which entered service in 1916], of which a large number were on hand at the close of the war. Our policy for the continued use of this plane is paralleled by that of the British Air Service, in which at the close of the war great numbers of this type were on hand and are still in use. A late report shows that the British Royal Air Force in their trans-Africa flight, recently completed, used DH planes substantially like ours and equipped with American-built Liberty engines [This is misleading. The RAF attempt to win the £10,000 prize offered by the Times was composed of four flights, only two of which made any real progress. Both of these used Vickers Vimys which were later destroyed in bad weather. The successful team, composed of Lt Col H. A. “Pierre” van Ryneveld and Lt C. J. Quintin Brand, flew the 1406 mi between Bulawayo, Zimbabwe to Cape Town, South Africa in a borrowed Airco DH.9A. The total flight from Surrey, England to Cape Town lasted from 4 February to 20 March 1920.]. Our DH planes now in service have been modified in design or have been reconditioned, and the same is true of war-built Liberty engines before being placed in use. This particular type of plane, though referred to by some critics as “flaming coffins,” has in the last three years been flown approximately 1,000,000 miles “cross country” on the Army airways without a casualty.

While the charge has been made in the public press that flyers have been compelled to fly in unsafe planes, no evidence of any such case has been submitted to us. It is clearly the duty of anyone [having any] such evidence to submit it to the proper authorities in order that those guilty of such a violation of rules shall be severely punished. Particularly is this the duty of any Army officer who has such knowledge. In the Army the channels of protest are as well known

-18-

as the channels of command and both are as old as the Army itself. Any member of the air service who has knowledge that his brother flyers are being forced into the air in unsafe planes and who fails to make direct and immediate report of the concrete case and facts to his chief is at fault to the extent that his knowledge is accurate.

Sums spent on research and development have been criticized. The justification for such expenditures is found in the rapidly changing character of the art. The outstanding contributions to our credit are evidence that sums spent for research and development have produced substantial results. In every art of civilization much of value is learned from failures, which indicate the closure of particular lines of research and the greater promise of others. Expenditures for research and development are the price of progress. Broadly viewed, we find no fair ground for criticism of such expenditures.

After careful consideration of the foregoing facts and criticisms as adduced in evidence we come to the third heading; -recommendations for legislative and administrative changes in the Army Air Service. We submit the following recommendations:

(1) To avoid confusion of nomenclature between the name of the Air Service and certain phases of its duties, we recommend that the name be changed to Air Corps. The distinction between service rendered by air troops in their auxiliary role and that of an air force acting alone on a separate mission is important.

(2) In order that the Air Corps (Air Service) should receive constant sympathetic supervision and counsel, we recommend that Congress be asked to create an additional Assistant Secretary of War who shall perform such duties with reference to aviation as may be assigned to him by the Secretary of War.

We foresee that such an official, properly used, could be the means of promoting close cooperation between aviation and the other parts of the Army. In the matter of procurement he could be especially useful. If the expenditures not only for new planes but for experimentation and operation were under the scrutiny of a civilian head, much of the feeling on the part of Congress that there was extravagance, and on the part of the Air Service that there was parsimony, might be avoided.

We feel, further, that such an assistant secretary, acting in con junction with the Assistant Secretary of the Navy and Assistant Secretary of Commerce, for whose appointment recommendations elsewhere provide, could perform in a continuous way from year to year, by investigation and recommendation, a substantial service to aviation.

(3) It seems desirable to give to aviation some special representation on the General Staff. There has not as yet been opportunity

-19-

for many aviation officers of suitable rank to be qualified for membership on the General Staff. We therefore recommend that the Secretary of War create, administratively, in each of the five divisions of the War Department General Staff, an air section, to be headed by a General Staff or acting General Staff officer detailed from the Air Corps (Air Service) ; such section, under the same supervision as other sections of its division, to consider and recommend proper action on such air matters as are referred to the division.

To accomplish this it may be necessary to waive in these instances some present qualifications for membership on the General Staff. This plan may seem inconsistent with one of the fundamental principles of the General Staff – namely, that no member represent any particular service. We think the good to be gained, however, justifies departure from the general rule. Obviously, the men designated for such staff positions must be of a temper of mind to appreciate not only the special needs of aviation but the needs of the Army as a whole.

(4) We recommend that Congress be asked to provide two more places for brigadier generals in the Air Corps (Air Service), to be detailed by the Secretary of War for the usual four-year period, upon recommendation by the Chief of the Air Corps; one such officer to be placed in charge of procurement, with a view to its eventual separation from operation, if later found desirable; another preferably to head the group of air-training schools near San Antonio, Texas.

(5) To provide rank commensurate with command during the present shortage of field officers in the Air Corps (Air Service), we recommend that Congress be asked to provide that the assignment by the Secretary of War of Air Corps officers to flying commands, such as wings, groups, squadrons, and schools, and not to exceed 12 important air stations, shall, when the Chief of the Air Corps certifies that no officers of permanent suitable rank are available for such assignment, carry with it the temporary rank appropriate to such command, for the period of such assignment. An officer enjoying temporary rank under this plan should not be eligible to command outside his own corps except by seniority under his permanent commission.

The award of such temporary rank to active flying officers will serve to fill a portion of the vacancies in field ranks now existing in the Air Corps (Air Service). This in our judgment should make it possible for the Chief of the Air Corps to approve transfers of suitable and physically qualified field officers from other branches of the Army to other vacancies in field ranks in the Air Corps without detriment to the morale of this branch. Such officers, of course,

-20-

should qualify in flying . All must concede the justice and propriety of putting only experienced flying men in the immediate command of flying activities.

(6) Considering the extra hazardous nature of flying, we believe that the principle of extra pay for flying should be recognized as permanent in time of peace. The administration of the provision for flying pay should be such that it will be paid only where the duties on which an officer is engaged may reasonably require flying or where necessary to keep him in training for future flying. We further recommend that a suitable study be made of the subject of insurance with a view to its provision if economically practicable and in order to furnish at least partial support for the family in case of death or for the flyer himself in case of physical disability resulting from flying.

We further recommend that there be instituted a special aviation medal and ribbon for extraordinary heroism in either peace or war.

(7) We find that there is a serious shortage of flying cadets and of Air Corps reserve officers. We recommend that suitable appropriations be requested in order to provide proper training of reserve officers and in order to provide necessary training planes and subsidiary flying fields for the use of the reserve.

(8) We recommend a very considerable increase in the number of institutions where ground instruction is given to Reserve Officers’ Training Corps units in the fundamentals of military aeronautics. Further adequate provision should be made at the Air Service training schools for annual summer training in flying, so that members of the Air Corps Reserve Officers’ Training Corps may qualify as military aviators and be able to receive their commissions in the same manner and at the same time as other members of the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps.

(9) We recommend that a careful study be made of the desirability of increasing the use of enlisted men as pilots in the Air Corps.

(10) The present is a transition period in the development of the Air Corps. New and approved types of airplanes to take the place of former models are now ready for production in quantity. For the next few years, therefore, special appropriations from the Congress are worthy of consideration. We do not consider it wise, however, to make definite plans for such an extended period as 10 years; we consider a plan looking forward over a period of not to exceed 5 years as more prudent. We therefore do not recommend the full realization of the plan of the Lassiter Board, but rather that the matter be made the subject of further study under competent authority.

-21-

II. THE NAVY

In a manner similar to that made use of in the instance of the Army, we may conveniently consider naval aviation under three headings: First, its strength and accomplishments; second, its condition in respect of personnel and matériel and the criticisms thereof; third, recommendations for its improvement.

Naval aviation is not a separate branch of the Navy, as the Air Service is of the Army. Its personnel and equipment are distributed throughout and form an integral part of the fleet. It is administered through the Bureau of Aeronautics in the Navy Department, which in turn is subject to the general supervision of the Chief of Naval Operations in much the same manner that the Army Air Service is supervised by the General Staff. On matters of personnel it is subsidiary to the Bureau of Navigation.

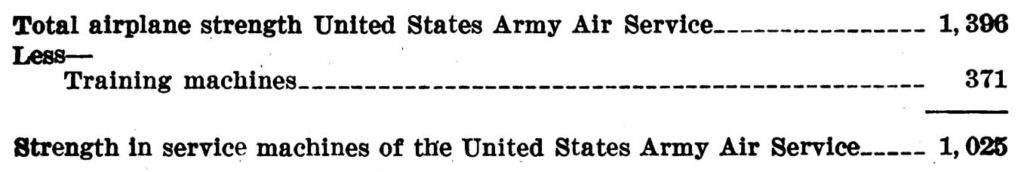

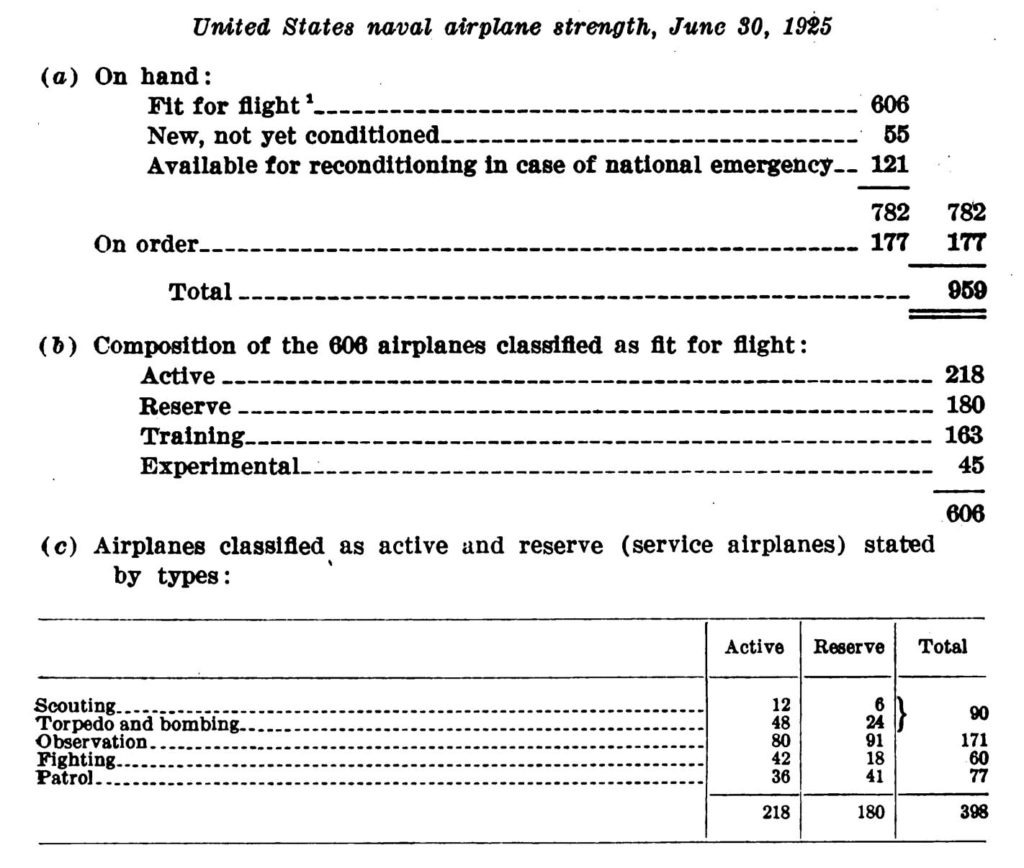

On June 30 last there were 398 service airplanes in naval aviation. Of this total 218 were with the fleet. The remainder were in reserve. In addition there were about 200 airplanes used for training or experimental purposes. In personnel there were 623 officers and 3, 330 men whose major duties were concerned with aviation. Of these officers, 377 were qualified pilots. These numbers are included in the total naval strength of 8,389 officers and 84,332 men. Appendix A, attached, gives a full statement of the strength of our naval air arm, together with some comparison with foreign countries.

In estimating naval air strength the following two factors must further be considered: First, the ability of the ships of the Navy other than aircraft carriers to utilize airplanes. To further this end catapults for the launching of airplanes are now installed on 25 to 30 combatant ships and are being provided for on others. Each of these ships carries from two to four airplanes. No foreign navy has accomplished anything substantial in this direction. Second, our strength in airplane carriers. We now have only one airplane carrier, the Langley [CV-1, converted in 1920 from the Proteus-class collier USS Jupiter (AV-3), itself first laid in 1912], which is a converted collier and has been used chiefly for experimental purposes. The Lexington and the Saratoga [CV-2 and CV-3, respectively; both were originally laid as battlecruisers in 1920/1921] which will be the largest and fastest airplane carriers in the world, will be commissioned in 1927. The treaty for the limitation of naval armaments governs our ultimate comparative strength in this class of vessel.

Our Navy was the first among those of the world to adapt the airplane to use on and over the sea. This was accomplished through the development of seaplanes and flying boats. In these types of airplanes we have continued to hold our lead. The Navy early developed the catapult for the launching of planes from ships. No

-22-

other navy has as yet produced a successful counterpart. We have done more extended cruising with large seaplanes than any other navy. Our naval aviators hold at least their share of world’s records and have to their credit many outstanding accomplishments, such as the first trans-Atlantic flight.

We find nothing but praise of the personnel engaged in naval aviation. The matériel at its disposal is likewise generally of high grade, as is shown by the almost total absence of criticism of matériel by the naval witnesses who appeared before us. From these facts and from considerations similar to those outlined in the in stance of the Army we believe that the quality of our naval personnel and of its equipment is at least the equal of and in certain directions undoubtedly superior to that of any other power.

There is a controversy in regard to the ability of airplanes under war conditions to sink the largest naval vessel. In our records will be found a complete summary of naval experimentation on this subject over the past 15 years. This is a highly technical question, and, in our opinion, any present answer must partake more of prophecy than of fact.

There is unrest and dissatisfaction among the aviation personnel in the Navy. They all agree in desiring to remain a part of the Navy. They feel that their devotion to aviation has prejudiced their chances for promotion and their opportunity for high command. They feel that the requirements for all officers to qualify in all branches ought not to be applied to aviators in its full rigor, as constant practice is essential to continued successful flying. These are among the most difficult questions we have been called upon to consider. There is justification, of course, for the contention of the higher officers that to be competent to command ships or fleets an officer must have sea experience. On the other hand, we feel that there should be a recognition of the principle that an officer with both air and sea experience should, other things being equal, be better fitted for command than an officer who has had sea experience only. We believe the solution lies in a broad and generous recognition of Admiral Mahan’s maxim [RDML Alfred Thayer Mahan (Ret.), author of the naval warfare treatise The Influence of Sea Power Upon History, 1660-1783 (1890)] that a naval officer should have a general knowledge of all branches of his profession and a specialized knowledge of one. Beyond this, however, it must be clearly recognized that special provision for promotion must be made for those officers who, through no fault of their own, have been confined solely to aviation duty.

As in the Army, we find the direct command of flying men by non-flying officers is objected to. This difficulty has arisen partly through the operation of causes discussed in the preceding paragraph, but more largely through the fact that there are no officers in the higher ranks of the Navy with long experience in aviation.

-23-

There appears to us justice in this contention, and we are recommending temporary advanced rank, following therein the same principle as in the case of the Army.

We find the criticism of deficiency in provision for reserve training in aviation to be justified.

Some apprehension has been expressed that special flight pay might be withdrawn and that the special insignia for officers qualified for aviation might be discontinued. These matters are covered in our recommendations.

There has been criticism of extravagance in naval expenditures on aviation. We do not find that this claim is established in any substantial degree. We find specific criticism of the continued operation of the naval aircraft factory. We believe that this factory should not be used on a production basis in competition with private industry, but that its maintenance for certain repair and experimental purposes is justified.

Another complaint is of insufficient officer personnel to provide for what are claimed to be reasonable plans for aviation expansion. One solution of this difficulty would be a larger Naval Establishment. With the present limited personnel, which is based on our national policy, the problem of the proper distribution of this personnel is a difficult one. There will naturally be differences of opinion until modern navies equipped with aviation have been subjected to the supreme test of actual warfare. We do, however, consider that every effort should be made to provide adequate aviation personnel to develop the possibilities of this new arm. Increased use of enlisted pilots would greatly assist in solving this personnel problem and should render unnecessary the increase of the Naval Academy.

It is thought by the technical staff officers who have been responsible for the development of our efficient naval aviation matériel that the present organization provides no posts of authority commensurate with their responsibilities; that the future promises little but continuation in subordinate positions. We have been able to find no immediate specific remedy for this situation, but are of the opinion that the claims of these officers deserve careful consideration by the Navy Department.

After careful consideration of the foregoing, we recommend as follows:

First. The appointment of an additional Assistant Secretary of the Navy under the conditions and for the purposes discussed else where in this report.

Second. The carrying as extra numbers, and at their own request, of officers (line or staff) of the grade of captain, commander, and

-24-

lieutenant commander, who have specialized in aviation so long as to jeopardize their selection for the next higher grade and thus insure such promotion as would be otherwise due.

Third. The giving of temporary rank as captain, commander, or lieutenant commander to any officer of a junior grade when he is detailed to duty requiring specialization in aviation and for which the higher rank is proper.

Fourth. The maintenance of flight pay as at present, but with the conditions and in connection with the insurance study recommended for the Army.

Fifth. Additional plans for, and suitable provisions for, the training of reserves.

Sixth. To the end that naval aviators should have the opportunity to present naval aviation problems to those responsible for the shaping of the policies and for the handling of the personnel of the Navy, we recommend that representation should be given naval aviators in details in both the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations and the Bureau of Navigation. We recognize that there are fundamental distinctions between the organization of the high command in the Army and the Navy. With a proper spirit of cooperation, however, we feel that the naval high command will find real opportunity to utilize the special knowledge and counsel of the naval aviator. This is analogous to the infiltration of Air Corps officers into the General Staff of the Army. Here, as in the Army, the particular men chosen must be of the temper of mind to appreciate not only the special needs of aviation but the needs of the Navy as a whole.

Seventh. Selections for command or for general line duty on aircraft carriers and tenders, or for command of flying schools, or for other important duties requiring immediate command of flying activities should be confined to those officers, who, while otherwise qualified, are also naval aviators; and such a policy should be followed as will provide a sufficient body of officers thus doubly qualified from which to select.

Eighth. An aviator assigned to general line duty for purposes of qualification in command should be disassociated from aviation to the minimum extent.

Ninth. Junior officers in aviation who, for any reason, have not had the required sea duty should have that duty before being examined for promotion.

Tenth. Special insignia for aviators should be retained and a special decoration for extraordinary heroism or achievement in aviation should be provided, as in the case of the Army .

Eleventh. A study should be made to secure a method through which sufficiently attractive careers may be provided in order to

-25-

retain qualified technical officers in naval aeronautic design and construction.

Twelfth. A study should be made of the desirability of increasing the use of enlisted men as pilots in naval aviation duty.

III. THE AIRCRAFT INDUSTRY

The importance of the aircraft industry in relation to national defense is obvious. The size of the air force needed in the event of a great war will always be far beyond anything that it is economically feasible to keep up in any country in times of peace. The rapidity of the development of the art of airplane design, rendering flying equipment inferior for service use against a major power within a few years after design, prohibits the gradual manufacture and accumulation of matériel and its storage for use in any future emergency. The airplanes to equip the expanded force in case of war must therefore be built when war is actually at hand, and the speed of their manufacture is a vital factor in military effectiveness. The relative wastage of equipment in war, too, is beyond anything known in peace, and production must be kept continuously at the highest pitch in order to supply the demands of the forces in the field.

The experience of the late war gives concrete illustration of the war-time and postwar problems of an aircraft industry and shows that in respect of the production of airplanes an international conflict coming without appreciable warning divides roughly into three successive parts. The first, lasting but a few weeks, is that in which dependence has to be placed on factory equipment and factory personnel actually in the service, before there has been time to get any program of expansion under way. It is succeeded by a somewhat longer period, during which the aircraft industry, using its existing facilities to the utmost and expanding them as rapidly as possible, delivers new airplanes to the service at a moderate but steadily increasing rate. In the third and final period the production of the aircraft industry proper is augmented by the incursion into the airplane field of a wide variety of plants normally engaged in manufacturing such things as pianos, furniture, automobile bodies, fancy hardware, and other articles not vitally necessary in the prosecution of war. When that stage is reached the rate at which airplanes can be produced in a highly industrialized country like the United States is very great.

The permanent aircraft industry is most important during the first and second stages and as a source of engineering development and supervisory talent at all times. For a few months, and they

-26-

would be among the most important months of any war, it would have to carry the full burden of supplying equipment. After others had begun to take a share of that burden the industry would still have the responsibility for the design of improved machines. The furniture manufacturer can not be expected to start experimental work or to do anything more than build from complete sets of drawings furnished to him. Anything that strengthens the industry as a whole, and especially anything that conduces to the strengthening of the design and engineering departments of the companies building aircraft, must be considered as a contribution toward the national defense.

There are certain obvious difficulties which preclude accurate appraisal of the capacities of the airplane industries of the United States and of the principal powers. Even in respect of many of the airplane-manufacturing plants in the United States data as to existing capacity submitted to us were found unreliable, data as to potential capacity were even more so, and corresponding data in respect of the aircraft industries of the principal powers were in most cases pure speculation.

We have taken into consideration (1) data obtained by the Industrial War Plans Division of the office of the Chief of Air Service, United States Army, as a result of the survey of the aircraft industry which was made during 1925 in conjunction with the Aeronautical Chamber of Commerce; (2) the data submitted by individual companies of the industry in response to requests from us; (3) the data as to World War production of airplanes compiled in the office of the Chief of Air Service; (4) the data obtained by personal visits to various plants by representatives of the Industrial War Plans Division. Upon the basis of this data, we estimate that the aircraft industry of the United States can be counted upon to contribute to the air strength of the United States during the first 12 months of a major emergency calling for the mobilization of the entire industrial resources and man power of the country, approximately 15,000 airplanes. This production would, of course, come in gradually, starting at a moderate figure and increasing steadily throughout the year. While the first year’s requirement of our military and naval services might not be met by this production (dependent upon the rapidity with which the other phases of our military and naval programs go forward), it is not apparent that any other power could make appreciably greater progress toward meeting its aggregate requirements within the first 12 months of a war. During the second year of the war new plants constructed or converted for mass production during the first year should be capable of bearing an increasingly greater proportion of the total war load, and it is probable that, at the end of 18 months, if not

-27-

sooner, our aggregate monthly production would be measurably greater than that of any other nation. In this connection it should be borne in mind that our geographic situation makes dire urgency of aircraft at the beginning of the war far less important for us than for European countries.

If a certain amount of business is needed to keep an essential industry in a sound condition, the amount of support that the Government must, directly or indirectly, provide decreases as the business coming from other sources is increased. It is, therefore, in the interests of economy and of efficient national defense that these other sources should be developed. Civilian operation of aircraft furnishes an obvious nonmilitary market for equipment. The sale of small airplanes to private owners affords another market and one which may be more important as time goes on. Outlets for American aircraft may also be found abroad. In this connection we are advised that other powers have sent official missions to foreign countries and that sales have resulted there from. American manufacturers should be encouraged in their efforts to develop an export trade.

It seems to us probable, however, that for some time to come the strength of the aircraft industry in the United States will depend primarily on the number of new airplanes ordered by the services. The determination of new policies will be of no avail to the manufacturers without orders for work to be done in the factories. This does not mean that the size of a government’s air force should be determined by the need of industry. On the contrary, the size of the air force must be determined solely on the basis of the large policy of national defense.

The gradual depletion of the war stock requires increase in the amount of new equipment ordered annually. In that respect the industry’s situation is assured of improvement. Whatever the size of the orders placed, however, they can be made to yield the best result both for the services and for the manufacturers if there is some continuity of policy and some clear aim.

It appears impracticable to make definite plans for the size of the air force at some period 10 years or more distant, and for the amount and type of equipment to be bought each year to reach that goal. Conditions change too rapidly. It does, however, seem feasible to lay down a general policy.