Carl A. Spaatz shortly after first arriving in Europe in 1942. By war’s end, Spaatz commanded more bomber aircraft than any field commander in history as CG USSTAF.

Special thanks to Michelle Kopfer of the Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library for providing scans of this document.

United States Strategic Air Forces in Europe, “Plan for Completion of Combined Bomber Offensive,” 5 March 1944, Walter Beddell Smith: Collection of World War II Documents, 1941-1945, Series VI: Air Force Operational Unit, Box 48 (Abilene, KS: Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library).

These papers have been reproduced as originally written, with spelling corrections and editorial additions highlighted and bracketed in blue. If you find any errors in my transcription, please do not hesitate to contact me. There were many spelling errors in this document, so it is quite probable that I missed a few.

Plan for Completion of Combined Bomber Offensive

SUPPLEMENT

REEXAMINATION OF PREVIOUSLY RECOMMENDED TARGET SYSTEMS

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

Parts 1 to 10 examine in abbreviated fashion the current target potentialities of seven industries, other than fighter aircraft, anti-friction bearings and rubber, which the C.A.S. [CAS MRAF Sir Charles F. A. Portal] and Casablanca directives [“The Bomber Offensive From The United Kingdom, CCS 166,” 24 January 1943] have specifically mentioned, together with grinding wheels (for which special consideration has been asked), tanks and tank engines, and the target system offered by German morale. The relevant conclusions of that examination may be summarized as follows:

i) Morale – This not a useful target system. Panic, war weariness and fear of impoverishment of Germans in general or particular, achieved through daylight bombardment of towns in general is not likely to speed disintegration of Nazi controls (Part 1).

ii) Railroad transport – Axis railroad motive power is not a useful target system. The interdiction of railroad communication, judged as a tactical objective, is not considered. Strategic attack on railroads, however, is judged to present too many targets, have too great a cushion of civilian and long-term industrial use, and stand too deep in time to offer a chance of achieving significant military effects (Part 2).

iii) Submarines – This is no longer a useful system. The strategic importance of submarines has declined with the full use of effective means of defeating them at sea. German U-boat construction is slacking off. No effects on enemy capabilities could be achieved in time to affect OVERLORD (Part 3).

iv) Aircraft engines – This is not a useful system. Heavy German losses in fighter assembly capacity have created an engine surplus. Destruction of engine capacity would rebalance the German industry but achieve long-run attritional rather than short-term military effects (Part 4).

v) Military motor transport – This is not a useful system. Low rates of turnover in civilian and military trucks protect military holdings from rapid reflection of the current level of output. Complete cessation of production would probably reduce military holdings only by 20 per cent in a year’s time (Part 5).

vi) Grinding wheels – This is probably not a currently useful system. In depth, it lies somewhat behind ball bearings with which it overlaps, and like rubber, it consists of another cut through the entire German economy. Seven plants produce 90 percent of European controlled-structure wheels, or 60 percent of grinding wheels of all types (Part 6).

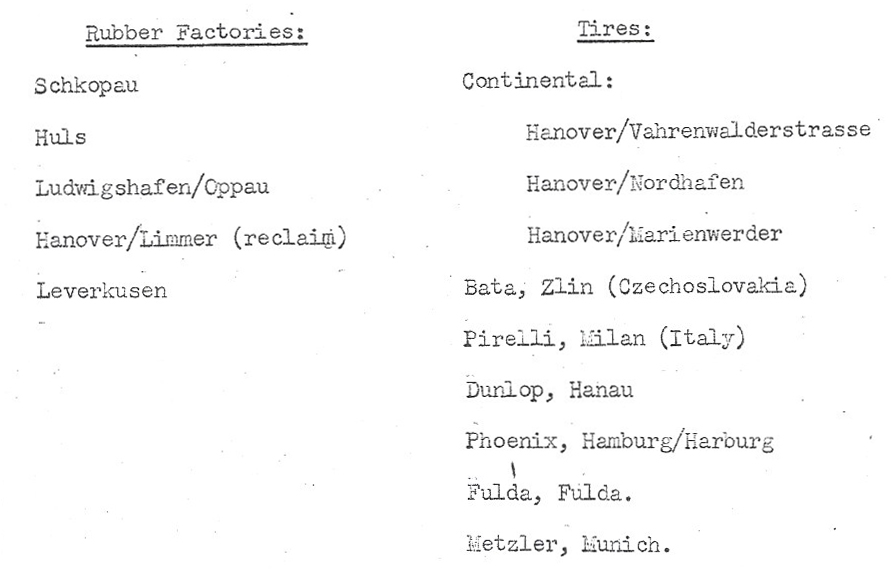

vii) Tires – Six targets in the field of tires constitute not a tire system, but a useful opportunity of destroying half-a-month’s supply of rubber and somewhat advancing the time at which the latter system will catch hold (Part 7).

-1-

viii) Tank engines and gearboxes – Three targets, two of them closely adjoining, offer a means of depriving Axis armies of 1000 tanks and assault guns within a six-month period beginning two to three months after successful attack (Part 8).

ix) Bomber Aircraft – Five bomber assembly factories merit early attack to reduce the weight of unsupported bomber night assault which the Luftwaffe can mount against OVERLORD. Since bomber turnover is slow, 5 months instead of 2-1/2 months for fighters, strength cannot be much reduced by D-day. Components, moreover, are not deserving of attack (Part 9).

x) Oil – 23 synthetic plants and 31 refineries currently account for over 90 per cent of total Axis refinery and synthetic oil output. 14 synthetic plants and 13 refineries account for over 8O% of synthetic production and over 60% of readily usable refining capacity. The effect of attack on these plants would fall more heavily on motor fuel than upon lubricant production. A special problem exists with respect to the refineries. If refineries in use are successfully attacked on a substantial scale, major refineries elsewhere, including idle refineries in Western Europe, must be watched and attacked when active. Petroleum stocks are believed to be of the order of three months consumption, including stocks in transit and at refineries and synthetic plants. These would be heavily drawn down to cushion the first effects of attack. With present air force capabilities, oil offers the most promising system of attack, after fighter aircraft and ball-bearings, to bring the German armies to the point where their defeat in the field will be assured (Part 10).

-2-

PART 1

PROSPECT FOR ENDING WAR BY AIR ATTACK AGAINST GERMAN MORALE

CONCLUSION

Day raids by American heavy bombers against German towns as such are considered to have little merit as a means of exploiting air supremacy over Germany. Neither fear, war weariness, nor the prospect of impoverishment is likely to be sufficient to enable impotent political and social groups to overthrow the efficient, terroristic Nazi social controls and bring about RANKIN [A set of contingency plans should Germany (a) suffer a catastrophic implosion of morale/capability before D-Day, (b) abandon its occupied territories, or (c) attempt to surrender following a political coup]. It is believed the German armies will have to be defeated in the field. At best, the prospect of such defeat as inevitable might induce the Army to purge itself of Nazis and assume power. The likelihood of this, prior to OVERLORD, is believed slim.

German towns, therefore, constitute targets for daylight bombardment only during prolonged periods of bad weather when precision objectives of direct military importance cannot be attacked. In these conditions, industrial towns are preferable to towns in general; and the industrial areas of towns, if selection is possible, are more advantageous targets than residential zones. It is not believed that administrative or commercial portions of the major cities like Berlin, Munich, or Vienna constitute exceptions to these targeting principles.

1. MORALE BOMBING

Attacks on German morale may be considered in terms of (a) terror; (b) war weariness and disgust; (c) concern for German post-war prosperity in general or particular. The methods usually considered as possible means of producing one or more of these effects consist in the daylight bombardment of:

a) German towns in general

b) large German cities

c) industrial targets chosen for their symbolic value

d) industrial targets chosen for possible political effects on specific key business or Nazi interests (aside from direct military target systems).

2. GERMAN WILL TO RESIST

The morale of the German people is already widely believed to be bad. To the extent that this means that the German civil population has little hope of victory and is anxious for defeat, this is probably correct. It is gravely doubted, however, whether the German people can take overt steps to hasten the acceptance of defeat by the German nation; or that further deterioration of morale will lead significantly closer to a position from which such steps can be taken by them.

Morale in a totalitarian society is irrelevant so long as the control patterns function effectively. The Nazi party controls have functioned well. Air raids have produced temporary local outbreaks, but opposition has had little opportunity to take overt advantage of the breakdown of communications, transport, and services in these periods. Social control is required to reestablish the conditions where life is possible. This the Nazi party has been sufficiently adaptable to provide.

3. THE MORALE OF THE NAZI PARTY

The will of the Nazi party to resist Allied military pressure springs from strong, simple urges. It is generally agreed, and is doubtless clear to the party’s leading members, that their changes for survival after RANKIN are slight. Their motivation in resistance is clear.

-1-

The Nazi party’s ability to organize recuperation is a possible point of attack. If the administrative problems thrust upon them by destruction of major cities were too large to be coped with, administrative breakdown might leave the party powerless. This is fact occurred for a short period with the failure of the evacuation scheme [likely a reference to the Kinderlandverschickung (Relocation of Children to Countryside) or KLV, a participatory welfare program created by Führer Adolf Hitler on 24 September 1940 that, by mid-1943, was incredibly unpopular]. But the impotence of other social and political groups is such that the war continues until gradually the party reassumes an adequate measure of control. Short of military defeat and occupation by United Nations’ forces, no group in Germany has shown itself sufficiently strong to contest the party’s position even in moments of administrative breakdown.

4. POTENTIAL OPPOSITION GROUPS

It is not believed that industry is likely to become a center of opposition to the Nazi party. Exerting its power through other social groups, it has never played an open political role. Moreover, in the last ten years it has been infused with Nazi leaders in key positions of management, and tied closely to governmental administrative institutions.

Banking and finance have no national leaders. The judiciary and the civil service are Nazi in complexion. The Church has no independent role or means of expression. The middle class has long been eliminated as a political factor.

The working class, from which effective opposition to the Nazi party might be expected to come, is profoundly war weary, but in no real sense organized to impose its will upon the nation. Its impotence in the face of Nazi controls, moreover, is a reflection not only of the ineffectual role it played in the ’20s and ’30s, but also of the negative character of its assumption of power in 1918. The monarchy was not overthrown by the working class. Power fell from its grasp, and the working class was sucked into the vacuum created by the absence of political control.

Finally, the Army. This has for some months been infused with reliable Nazis, both in the High Command and in the younger officers taken in directly from the Hitler Youth. Yet it alone has the chance of providing opposition to the Nazis. Its interest is so doing would be based upon desire to disassociate itself in defeat from guilty Nazi political leadership, and preserve some semblance of dignity for German military tradition. Its capacity for so doing lies in the possibility of forcibly removing outstanding Nazis from power in the Army, then seizing political control by force or threats of ceasing resistance.

5. RELEVANCE OF DAYLIGHT BOMBARDMENT OF TOWNS TO POLITICAL POWER

If the Army is the only social or political group in Germany capable of wresting control from the Nazi party, it follows that neither aerial bombardment of towns calculated to terrorize, nor destruction of wealth in the control of influential individuals will avail much in producing German defeat on grounds of morale. A breakdown of Nazi party control is not excluded. The circumstances under which any group other than the Army can restore control, however, is minimal. And the Army is likely to oppose the party on such an occasion only when it has judged inevitable its defeat in the field.

Army calculations of advantage are not in the least likely to be affected by the fears of the people or their weariness. Their refusal to work or of soldiers to fight would be, another matter. Mass refusal is unlikely since the first several thousand, at least, would be shot. Of far more importance to the Army are factories in which German people may work, and weapons with which the Wehrmacht may fight. Attacks on industries of direct military importance, therefore, are far more capable of producing significant effects on Army political moves than attacks on non-industrial areas.

-2-

PART 2

TARGET POTENTIALITIES OF AXIS EUROPEAN TRANSPORT – MARCH 1944

CONCLUSION

Axis European transportation cannot be recommended as a target system for strategic attack. Military traffic forms a small proportion of total traffic; at its maximum it will not be more than about one-fifth of total traffic. A reduction of at least 30% could be made in European rail traffic (the most important part of the traffic system, and the part which is relatively vulnerable to air attack) without affecting enemy military potential for a year. To effect a reduction of this order would demand attack on more than 500 targets. At least 250 of these targets are major workshop areas of heavy construction, requiring a large weight of bombs. Attritional strategic attack on Axis transport is therefore considered undesirable. The present report does not treat the merits of interdiction of lines, which constitutes mainly a tactical problem.

1. THE TRAFFIC SYSTEM

Total freight traffic in Axis Europe is currently estimated at about 2 billion tons, or 400 billion ton kilometers. Of this, about three-quarters (both in terms of tons and ton kilometers) is carried on the railways, and nearly a quarters on the inland waterways. The contribution of coastal shipping, while important for certain specific hauls, is small in overall terms, and highway traffic is negligible.

Attritional attack on transport in general (which is the only type considered in this note; as contrasted with attacks on specific movements at specific times) must be directed chiefly at the railways. The waterways carry a quarter of the total freight traffic, which consists of coal, building materials, timber, and grain, while practically none of it consists of military supplies. Further, most water-borne traffic is on natural river waterways relatively invulnerable to attack. At present, direct military traffic – munitions and other supplies shipped to field units – constitutes about one-sixth or less of total rail traffic. Most Of this is on the Eastern Front. In the period of heavy fighting and maximum troop movements in France, the average proportion of military traffic over any period of time will not rise over about one-fifth of the total, and may not rise at all if the retreat in the East continues.

2. DEPTH

More than two-thirds of the total railway freight traffic consists of coal and coke, construction materials, iron ore and other minerals, unprocessed bulk foodstuffs, fertilizers, and iron and steel mill products. A reduction in the supply of these items would not make itself felt on the fighting fronts for a considerable time. None of the classes is, on the average, less than six months away from finished armaments in the production cycle, and the existence of stocks and pipelines means that they are seven or eight months from the front line. Some items, like fertilizers, and construction materials, may be as much as twenty months deep. The average depth of the whole rail transport system is certainly as great as the average depth of the whole production cycle; this is at least nine months, and may be as much as a year.

3. STRATEGIC RELATION TO OVERLORD AND AFTER

The fact that direct military traffic is not expected to constitute more than one-fifth of total rail traffic even during the period of intensive fighting and high reinforcement rate which will follow the invasion of Western Europe means that a 30% cut in traffic will have no effect on OVERLORD.

The great depth of the transport system means large reductions could be made in rail transport without affecting military capabilities for some times. It is estimated that a 30% reduction in railway traffic, falling largely on coal, iron ore, fertilizers, construction materials, and agricultural products could be sustained for at least a year without affecting the strength of the Wehrmacht in the field. Thus the military position of the enemy would

not be affected within, a relevant period by any attack on transport in general which could be mounted. (See below, paragraph 4.)

4. TARGETS

A sustained reduction in the carrying capacity of the railway system in general can best be achieved by an attack on serviceable locomotives. Attack on other possible sub systems such as rolling stock or permanent way facilities would each require a much larger effort to achieve the same effect. Locomotives are in relatively shorter supply than freight cars on the continent today. Moreover, the destruction of a similar proportion of the total stock would demand attack on a greater number of targets. The railway network of Germany and Western Europe is so dense, and repairs to most permanent way facilities so quickly effected, that no considerable sustained reduction in traffic can be achieved by feasible effort against the rail network.

In order to achieve a reduction of 30% in railway freight traffic, enough locomotives would have to be put out of action to eliminate all passenger traffic above the absolute minimum possible (estimated at 50% of the present passenger train mileage) as well as to cut down freight service. There are a total of about 54,000 serviceable mainline steam locomotives in Axis Europe today, and about 10,000 more being overhauled in major repair shops. The reduction of freight traffic by 30% would require a reduction of this number by nearly 20,000 locomotives, in addition to normal wastage and sabotage.

At any one time serviceable locomotives would be found more or less equally distributed between open railway lines and locomotive sheds. There are about 3000 locomotive sheds in Axis Europe. The 20 largest would at any one time contain at most 1400 locomotives; the next 40 might contain another 1400. Heavy attack on these 60 targets might thus result in the destruction of about 2500 locomotives. It is doubtful that heavy attack on the next 100 sheds would contribute more than another 2500 locomotives.

During a six-month period, the 36 producers of main line steam locomotives will produce about 1500 locomotives. Destruction of these 36 plants would mean the reduction of the total by 1500 locomotives. In the same period, about 13,000 locomotives will go to major repair shops for overhauls. There are about 200 major repair shops in Axis Europe; the 50 largest do about one-third of the total repair work. Destruction of these 50 would result at most in an increase in unserviceable locomotives and a destruction of locomotives of 5000 in this six month period.

An additional burden on the railroads equivalent to the loss of about 3000 locomotives could be achieved by stopping traffic on the Mittelland Canal in Germany. Successful attack on 16 targets – 2 ship elevators, 5 aqueducts, 7 locks, and 2 embankments, would render the whole canal unusable.

Thus successful attacks on 262 targets would result in a reduction of the locomotive supply by about 14,500 units. The reduction of efficiency in handling the locomotives in the neighborhood of the larger sheds which have been destroyed might be equivalent to another 500 locomotives, bringing the total up to 15,000. Thus the destruction of 5000 locomotives by other means is required to fulfill the program. This could be done in part by strafing and bombing individual locomotives – which has up to now achieved a maximum rate of destruction of considerably less than 1000 in six months, and in part by further attack on locomotive sheds containing fewer than 20 locomotives each.

5. VULNERABILITY

Except for the 16 waterway targets, all the targets discussed above require heavy attack to produce major damage. The buildings of locomotive sheds, repair shops, and producers are all large and strongly built, with gantry cranes and generally with steel framing. Minor damage to these buildings will have little effect on activity, since equipment and contents are very heavy.

The average locomotive shed and surrounding track area on which locomotives are parked consists of about 10 acres, of which the shed comprises 3. A major repair shop or factory may have a plant area of 100 acres or more, of which 50% is covered by buildings.

6. POSSIBLE DAMAGE AND EFFECTS

It is doubted that any scale of attack can be mounted which will achieve destruction of the listed targets in six months or even a year. If this were achieved, no military effect would be felt for more than a 9 months following the completion of the program. Therefore no significant military effect can be expected from attack on this system in any relevant time period.

PART 3

TARGET POTENTIALITIES OF SUBMARINES – MARCH 1944

CONCLUSION

The self-imposed German decrease in submarine production supports the conclusion that anti-submarine techniques have diminished the effectiveness of this weapon to the point where increasing the already large fleet is deemed unimportant. This fact plus the known slight vulnerability of building installations and the long period between construction and operational use justifies the conclusion that attack upon submarine yards is no longer warranted.

1. PRODUCTION, NUMBERS AVAILABLE, DEPTH

Germany had 271 submarines under construction in June 1942, 270 in June 1943, but only 200 as of February 1944. Completions have fallen from over 22 to less than 18 per month.

Since a minimum of 1 to 11 years elapses between the laying of a submarine keel and the day it joins the fleet, only a small addition (perhaps 50 submarines) to the present number is likely before OVERLORD.

450 units make up the German submarine fleet. Completions and destruction keep the number of U-boats in the operational fleet roughly constant.

2. STRATEGIC RELATION OF SUBMARINES TO FUTURE OPERATIONS

U-boats are used chiefly against trans-oceanic supply routes. They may be used, but to an even less effective extent, against actual invasion shipping. Ships already in existence represent almost the entire potential for operations of either type. A slight increase in numbers will hardly affect the effectiveness of this weapon.

Furthermore, present anti-submarine techniques are believed to have diminished the effectiveness of submarines in either use to an extent justifying the conclusion that they will have only the most indirect effect on future military operations in the European theatre.

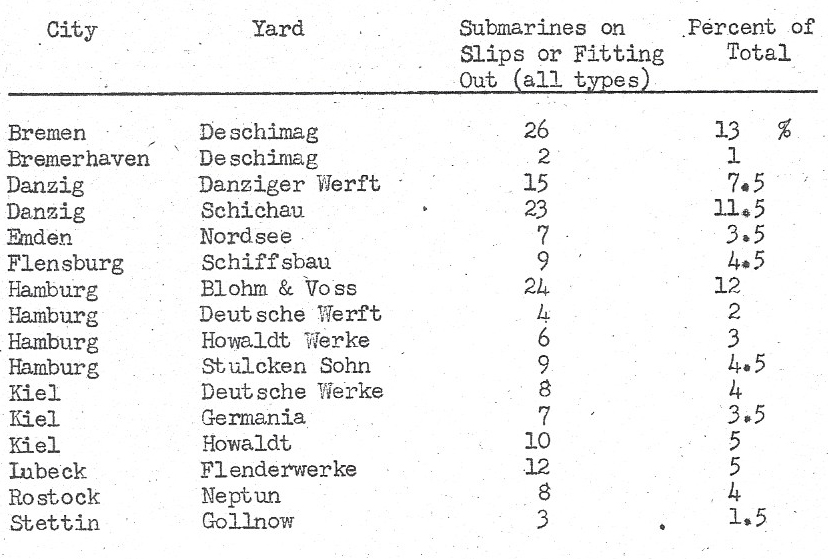

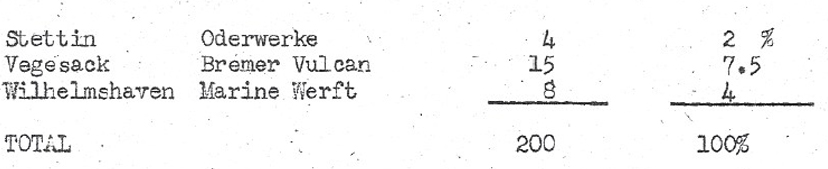

3. TARGETS

Submarines are produced in 19 yards in 12 German cities. Essentially these yards are assembly shops producing submarines from components manufactured all over Occupied Europe.

4. VULNERABILITY

Damage assessment demonstrates that submarines under construction are virtually invulnerable to ‘anything but a direct hit. With fewer submarines being produced the relatively higher percentage which may be built on covered slips makes this possibility of even lesser interest. Complete destruction of yard facilities such as power plants, metal working shops, slips, and the like has proved difficult, and the comparative resilience of the industry through ready replacement or repair has resulted in only minor delay from even the most successful raids.

5. STRATEGIC EFFECTS OF PROSPECTIVE DAMAGE

Perhaps the best evaluation of the expected future importance of submarine warfare is found in Germany’s apparently self-imposed decrease in production after Allied anti-submarine techniques had proved effective, as opposed to increased production during the period of heaviest attacks upon yards. This fact plus the small contribution to total strength possible during the next six months and the proven invulnerability of installations to attack renders the possibility of further yard damage of little probable strategic effect.

PART 4

TARGET POTENTIALITIES OF AIRCRAFT ENGINES – MARCH 1944

CONCLUSION

Allied attack against airframe factories and assembly plants has already created a sizeable engine surplus. The shortage of ball bearings impedes engine production. Under these circumstances, attack on engine manufacture and assembly is not considered warranted. This conclusion is not subject to modification for special types. Attack should rather be pressed further against aircraft themselves.

1. PRODUCTION, STRENGTH AND DEPTH

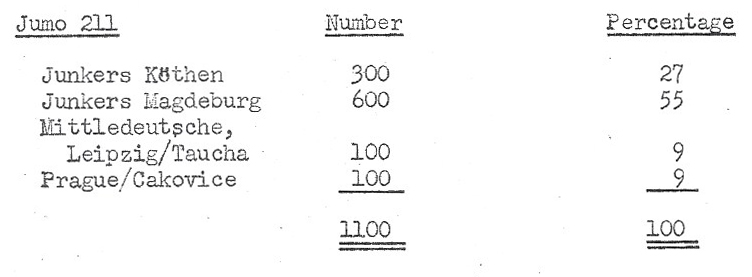

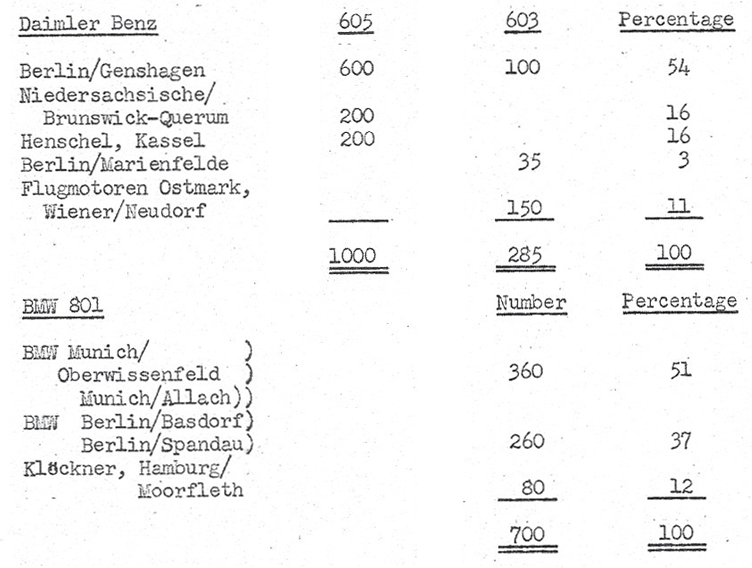

Production of engines for operational aircraft before the February raids on airframe factories was believed to be roughly 1100 Jumo 211s [The Junkers Jumo 211 was primarily used by the Junkers Ju 87, Ju 88, and Heinkel He 111] per month, 1000 DB 603s and 605s [The Daimler-Benz DB 603 and 605 were primarily used by the Messerschmitt Bf 109 and Me 410], and 700 BMW 801s [The Bayerische Motoren Werke (Bavarian Motor Works) BMW 801 was primarily used by the Focke-Wulf FW 190]. Repair output of the three major types was around 1000, 1000, and 600 respectively. The rate at which engine manufacturers will operate, following the recent destruction of aircraft plants, is difficult to estimate: first, because of the lowered requirements; and second, because of the unknown effects of ball bearing shortages. Undoubtedly all engine plants will be cut back substantially. The following table shows the probable excess of previous production rates over the present requirements for engines to go into new aircraft:

In addition, the decreased scale of operations forced on the GAF [word obscured] the reduction in supply of new aircraft will reduce the demands on engine plants for production of spare engines and spare parts.

In addition, the decreased scale of operations forced on the GAF [word obscured] the reduction in supply of new aircraft will reduce the demands on engine plants for production of spare engines and spare parts.

2. TARGETS AND PERCENTAGE CONTRIBUTION

Following is a table of the producers of the three major operational engines, showing their rates of production before February. In some cases, such as Wiener Neudorf, this does not present full capacity, but illustrates only the reduced level of operations following earlier attacks on airframe makers.

3. VULNERABILITY

Engine manufacturing is fairly well concentrated. A large proportion of the casting and forging processes are subcontracted but remaining work is largely done at the main plants. These are largely typical of light engineering plants. The machines themselves are largely of conventional types, except a few special installations for gear cutting and cylinder grinding, and are moderately vulnerable to fire.

4. PROSPECTIVE DAMAGE POSSIBLE AND STRATEGIC EFFECTS

Because of the large excess of engine capacity over requirements, a disproportionate amount of damage would have to be inflicted on the entire engine industry before any strategic effect would be gained against final aircraft output. Even the production of the DB 603, which seems to be well concentrated, could be shifted to any of the other Daimler Benz plants. Attack against it would have to be directed against the whole Daimler Benz system. Direct results on the strength of the GAF in operational aircraft at D-Day and thereafter may much more effectively be gained by continuing to confine attacks to aircraft plants.

PART 5

TARGET POTENTIALITIES OF MOTOR TRANSPORT VEHICLES – MARCH 1944

CONCLUSION

Attack on motor vehicle factories cannot significantly affect German military mobility within a short period of time. As a long run target system the impairment which such attacks would impose on the Wehrmacht and industry in a year would be useful but of disappointing magnitude: perhaps of the order of a 20 percent reduction in present holdings. Wastage is a small proportion of holdings.

1. PRODUCTION, MILITARY USE, AND RATE OF TURNOVER

Production of trucks in Axis Europe is estimated at 100,000 per year. At least 90 percent of this output is for military use. The remainder is for essential industrial use. Truck holdings are roughly estimated to total slightly over 1 million, of which about 500,000 are military holdings. Perhaps 200,000 civilian vehicles are suitable for military use. Wastage is estimated at 200,000 per year, of which 165,000 is military truck wastage. The rate of military truck wastage is thus about 35 percent per year, while civilian truck wastage is 10 percent or less per year.

2. DEPTH

On the average, completed trucks at assembly factories are one to two months behind military use in theaters of operation, or alternatively several weeks behind use in Germany and Western Europe.

3. STRATEGIC RELATION TO OVERLORD AND AFTER

Adequate numbers of trucks are, of course, essential to German resistance to OVERLORD. Since the number of trucks which will be produced in the next six months is but 10 percent of the military holdings available to the Germans (and a somewhat smaller percentage of military holdings plus useful civilian motor transport), the significance of truck production to OVERLORD is negligible. Supplemental attacks on motor vehicle parks could likewise not be expected substantially to affect OVERLORD opposition, unless undertaken immediately prior to D-day.

If truck wastage over the next year were not replaced, probable requisitioning of 50,000 to 100,000 vehicles from the civilian economy would hold shrinkage in net military holdings to about 20 percent. The result would be a useful impairment of military mobility and a greater impact upon economic productivity.

4. TARGETS

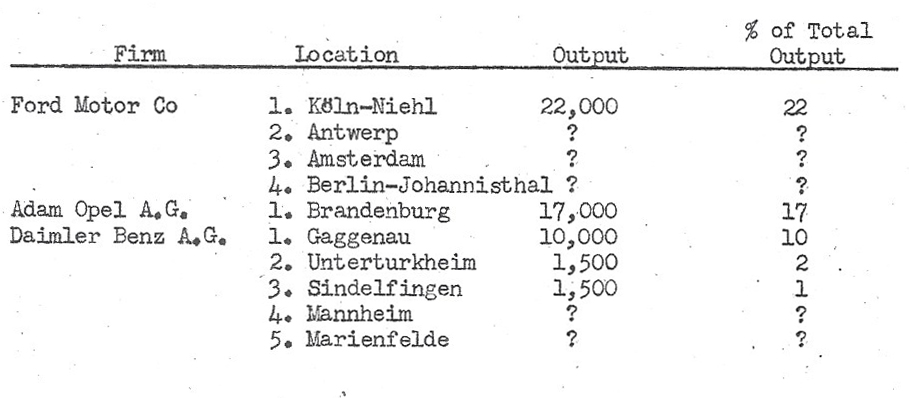

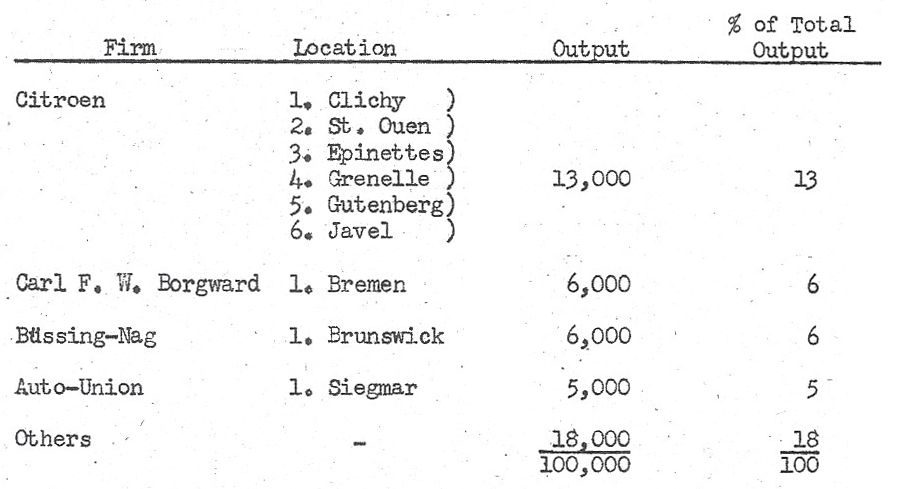

The major truck producers and their estimated output are presented in the following table. Plants without output figures con-tribute in unknown amounts to the. other plants of the same company.

5. VULNERABILITY

Truck factories have the same moderate order of vulnerability as other light and medium engineering plants. Most German plants have only the conventional machine tools which could be replaced after bombing.

6. PROSPECTIVE DAMAGE POSSIBLE AND STRATEGIC EFFECTS

Successful attack of this target system would not have significant military effect for at least a year. This is due to the low ratio of truck production to military holdings and to the possibility of requisitioning civilian trucks. The magnitude of effect which would then take place would be less than that which can be expected from successful attack against the rubber target system, to which it is an alternative.

PART 6

TARGET POTENTIALITIES OF GRINDING WHEELS – MARCH 1944

CONCLUSIONS

A concerted series of attacks upon seven grinding wheel plants will have a useful effect in decreasing the productivity of a wide, if unpredictable, range of armament and engineering industries. Such effect will begin to make itself felt upon German industry within 3-4 months and upon military capabilities within 5-7 months of completion of the attacks.

1. PRODUCTION, CONSUMPTION AND STOCKS

German European production and consumption of grinding wheels were both recently estimated to be of the order of 36,000 tons per annum. Stocks were believed equal to two months requirements. Since grinding wheel requirements have presumably decreased as a result of recent attacks on ball bearing, aircraft and other machining plants without any significant parallel decline in production, present stocks may be roughly estimated equal to 3-4 months requirements.

2. STRATEGIC RELATION TO OVERLORD AND AFTER

Available stocks render unlikely effects from even immediate attacks on grinding wheel plants before OVERLORD. However, within 3-4 months of simultaneous or nearly simultaneous destruction of key grinding wheel plants, production of all types of engines and components, crank-shafts, piston rings, ordnance components, gears, machine tools and all other products requiring close tolerances would be seriously, if perhaps unpredictably impaired.

3. TARGETS

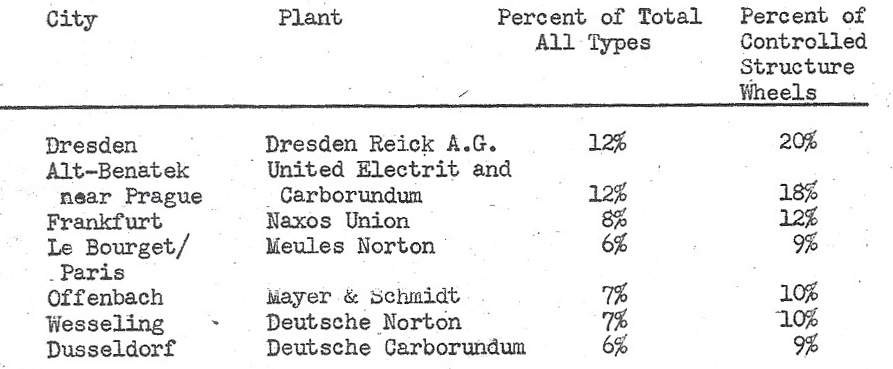

Nearly 60% of all German European grinding wheels are produced in seven plants. These plants account for 90% of all controlled structure wheels (reputedly of higher precision):

4. VULNERABILITY

The kilns in which grinding wheels are fired are highly vulnerable to H.E. and are probably quite vulnerable to blast. Replacement times vary from six weeks to six months depending on the size and type of kiln. It must be particularly noted, however, that the limited number of experienced repair and construction personnel would impose serious delays if several plants were attacked at the same time.

5. STRATEGIC EFFECTS OF POSSIBLE DAMAGE

Concerted attacks against the seven leading producers will have an important overall effect upon production of a great but unpredictable variety of military equipment and machine tools. Because many consumers employ semi-skilled help, variations in the specifications of grinding wheels produced by smaller firms and presumably to be made available to high priority consumers who are deprived of their normal source of supply, will offer a significant bonus in the form of decreased productivity.

PART 7

TARGET POTENTIALITIES OF TIRES – MARCH 1944

CONCLUSION

Tires do not constitute an important primary target system. The six major factories, however, have some value as secondary targets for filling out missions planned about more significant targets. The destruction of their contents by successful incendiary attack would liquidate stocks of rubber in bulk and in process, and thus reduce by half a month the time required for the main impact of the attack on rubber output.

It is not likely that the destruction of tire factories of tire stocks in military [depots] in Western Europe could affect enemy capabilities of resisting OVERLORD.

1. PRODUCTION, DEPTH, AND TURNOVER

(i) Axis tire production is estimated to be about 200,000 per year of which perhaps 150,000 covers are required for motor vehicles. The remainder are chiefly airplane tires. To a considerable extent, capacity is interchangeable among various types of tire output. A large volume of excess plant capacity exists. Shortage of rubber is the limiting factor on production.

(ii) Stocks of tires on military vehicles, in depots, and on civilian vehicles are probably sufficient so that no immediate effect could be gained by the loss of tire making capacity. Between five and ten percent of the tires in service must be replaced each month. Loss of synthetic and reclaim rubber capacity will produce effects on the serviceability of German military equipment in perhaps 6 months. The loss of rubber at tire plants is a moderately useful reinforcement of successful attack against rubber production.

2. STRATEGIC SIGNIFICANCE

(i) Most newly produced tires are used as replacements on motor vehicles in service. New motor vehicles absorb 10 to 15 percent of monthly output. Since tire replacement and retreading are to some degree postponable, the immediate effect of loss of both synthetic rubber and of tire output would only be to require still further economies in German usage. After three months, however, tire stringencies would begin to impinge gradually and cumulatively on military mobility and industrial activity.

(ii) It may be seriously doubted that the loss of tire output now would affect German ability to resist OVERLORD. Even if the tire depots in Western Europe could be located, their destruction by fire, superimposed on the loss of new output, would have attritional effects rather than impair tactical mobility.

3. TARGETS

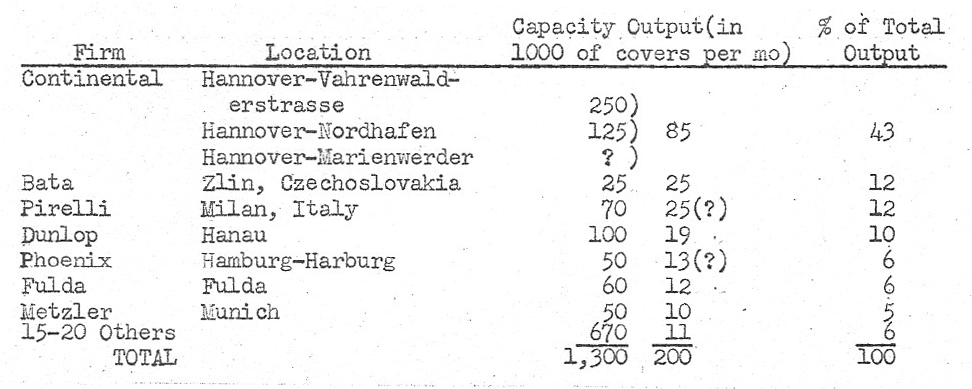

The following list presents output figures for the six major targets, as well as for some of the smaller operating plants:

4. VULNERABILITY

Tire plants have the characteristic of high vulnerability to fire. They are also relatively small and compact in layout.

5. PROSPECTIVE DAMAGE POSSIBLE AND STRATEGIC EFFECTS

About one-half month’s loss of rubber supplies would result from successful attack upon the six largest targets listed above. This would hasten the impairment of military mobility and industrial activity which would result from destruction of the rubber target system.

PART 8

TARGET POTENTIALITIES OF TANKS, TANK ENGINES, TANK GEARBOXES – MARCH 1944

CONCLUSION

Three significant targets exist in the field of tank engines and gearboxes. Their destruction would produce a material loss of tank output in the third to sixth months following attack. This result would not affect early enemy resistance to OVERLORD, except perhaps by inducing him to employ his tanks more conservatively (a qualitative benefit to our landing), and through slowing down tank allocations to the Eastern Front. Once our landing had been assured, however, the lack of tank replacements would gradually be felt quantitatively.

1. PRODUCTION, STRENGTH AND DEPTH

Ground evidence of German efforts to increase tank production appears to justify increasing estimates from 400 (based on analysis of serial numbers) to 500-600 units per month. First line strength is believed to be of the order of 4000 tanks. The normal intervals from completion of engines and completion of tank assembly to delivery to first line units are four and two months respectively.

2. STRATEGIC RELATION TO OVERLORD AND AFTER

Destruction of tank assembly or tank engine plants will not affect first line strength before D-day. Thereafter, within the relatively limited defensive importance of tanks, inability to replace tanks should detract from German defensive capabilities by imposing limitations upon the mobility of overall available weapons. The prospective loss of replacements may, moreover, result in the conservative employment of tanks in first line units, except in the enemy’s exploitation of major opportunities.

3. TARGETS

There are eleven or more tank assembly plants; in the absence of evidence of relative size, these are assumed to be of approximately equal importance. Because of the possibility of using other heavy industry plant, the relative invulnerability of such factories and lack of evidence of a higher degree of importance of any of the plants, attack on assembly plants is not recommended. Several of them have suffered varying degrees of damage.

Serial number analysis indicates that two plants, Maybach Motorenbau [Maybach Engine Construction] at Friedrichshafen and Norddeutsche Motorenbau [North German Engine Construction] at Berlin produce all or nearly all tank engines. Maybach designs all and produces approximately twice as many engines as Nordbau. Maybach also may be important as an engine repair center and gear box producer. The Zahnradfabrik [Cogwheel Factory] in Friedrichshafen supplies a majority of all tank gears.

4. VULNERABILITY

Tank engine and gear plants contain some specialized but, for the most part, general purpose machinery. The three plants named under paragraph 3 are fairly typical light engineering plants of a type believed vulnerable to HE attack.

5. STRATEGIC EFFECTS OF POSSIBLE DAMAGE

Assembly plant stocks of engines and gear boxes are sufficient to prevent any decline in final assembly for approximately two months following severe damage to Maybach, Nordbau and Zahnradfabrik. The

six months following such damage, however, would result in an overall loss of approximately 1000 tanks, with consequent impairment of enemy military capabilities.

1. Fully tracked self propelled guns are treated as tanks in this report.

PART 9

TARGET POTENTIALITIES OF BOMBER AIRCRAFT – MARCH 1944

CONCLUSION

The destruction of the German fighter aircraft industry deprives bombers of their most significant possible relevance to D-day, i.e. daylight attack on Allied beaches, shipping and [ports] of embarkation. Potentialities of night attack, however, are such as to merit some consideration to the target system.

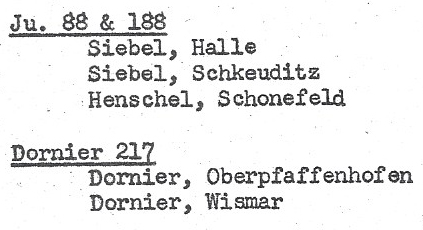

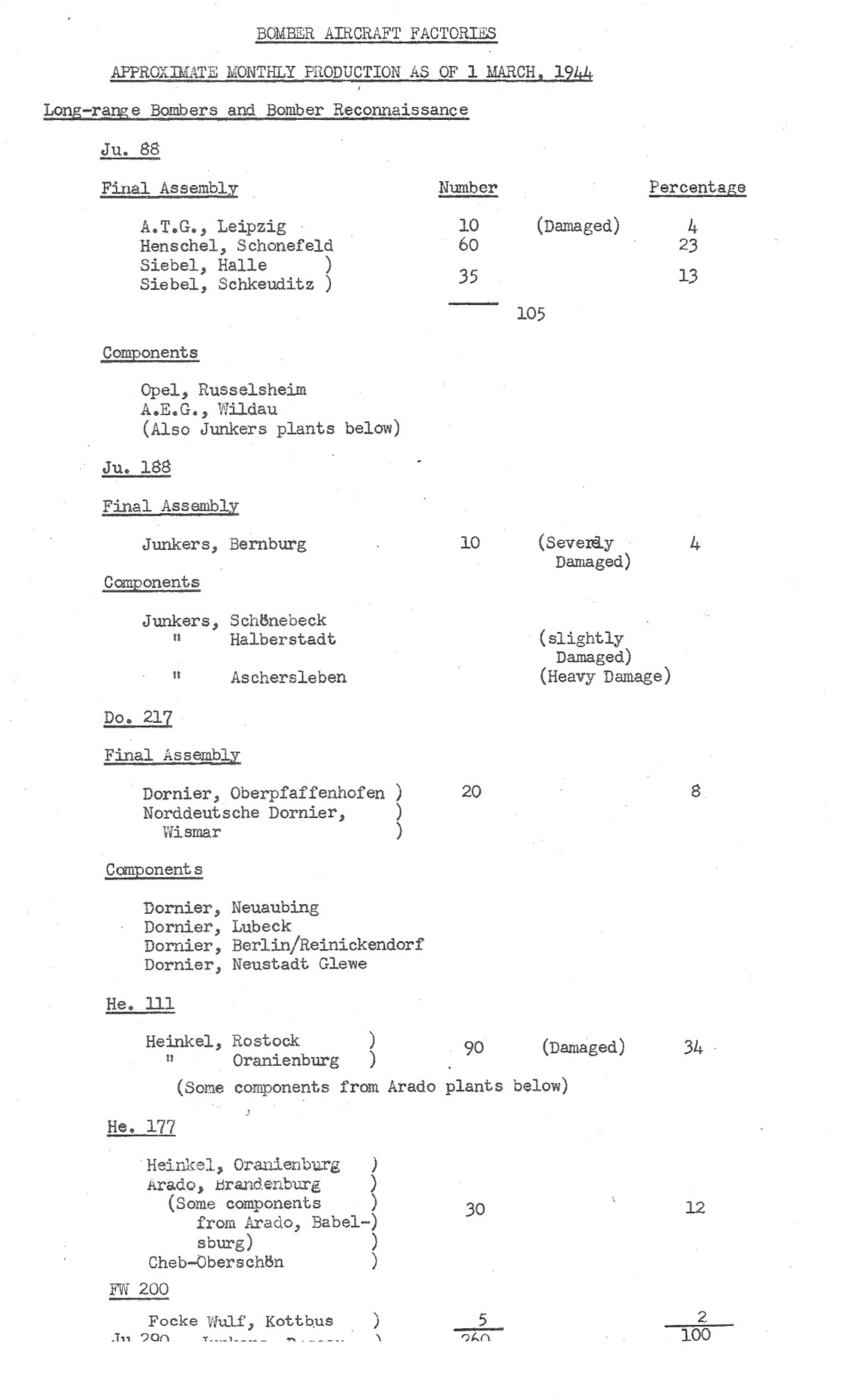

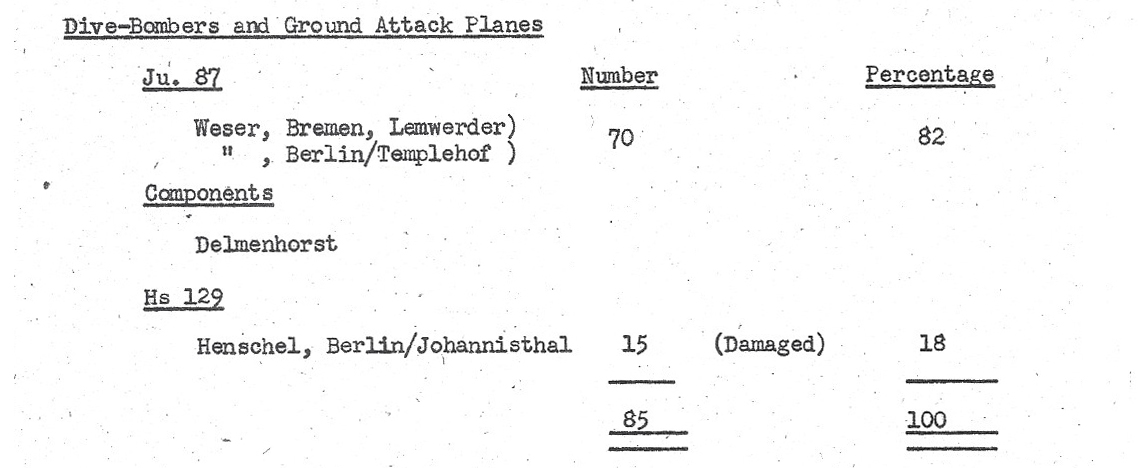

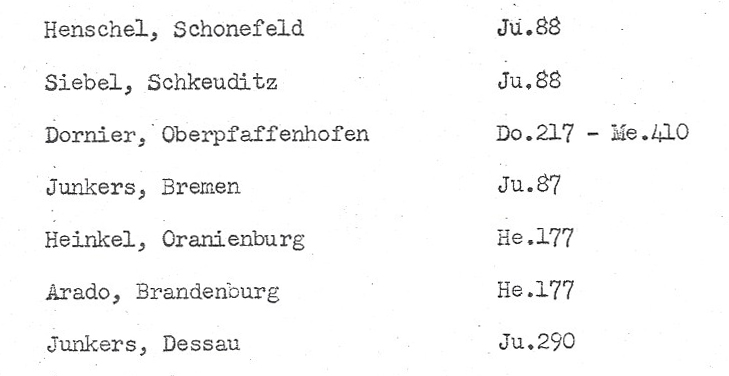

Bomber aircraft production and repair now constitute 25 percent of total strength. Attack on final assembly factories for Ju. 88s and Do. 217s would have some effect on the forces available to the GAF on D-day. Deeper attack, felt later, would not be warranted. On qualitative grounds, attack on other types than those mentioned would be wasted.

1. PRODUCTION, STRENGTH, AND DEPTH

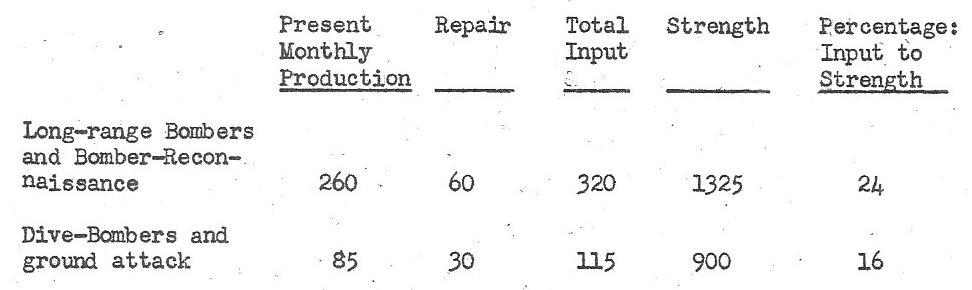

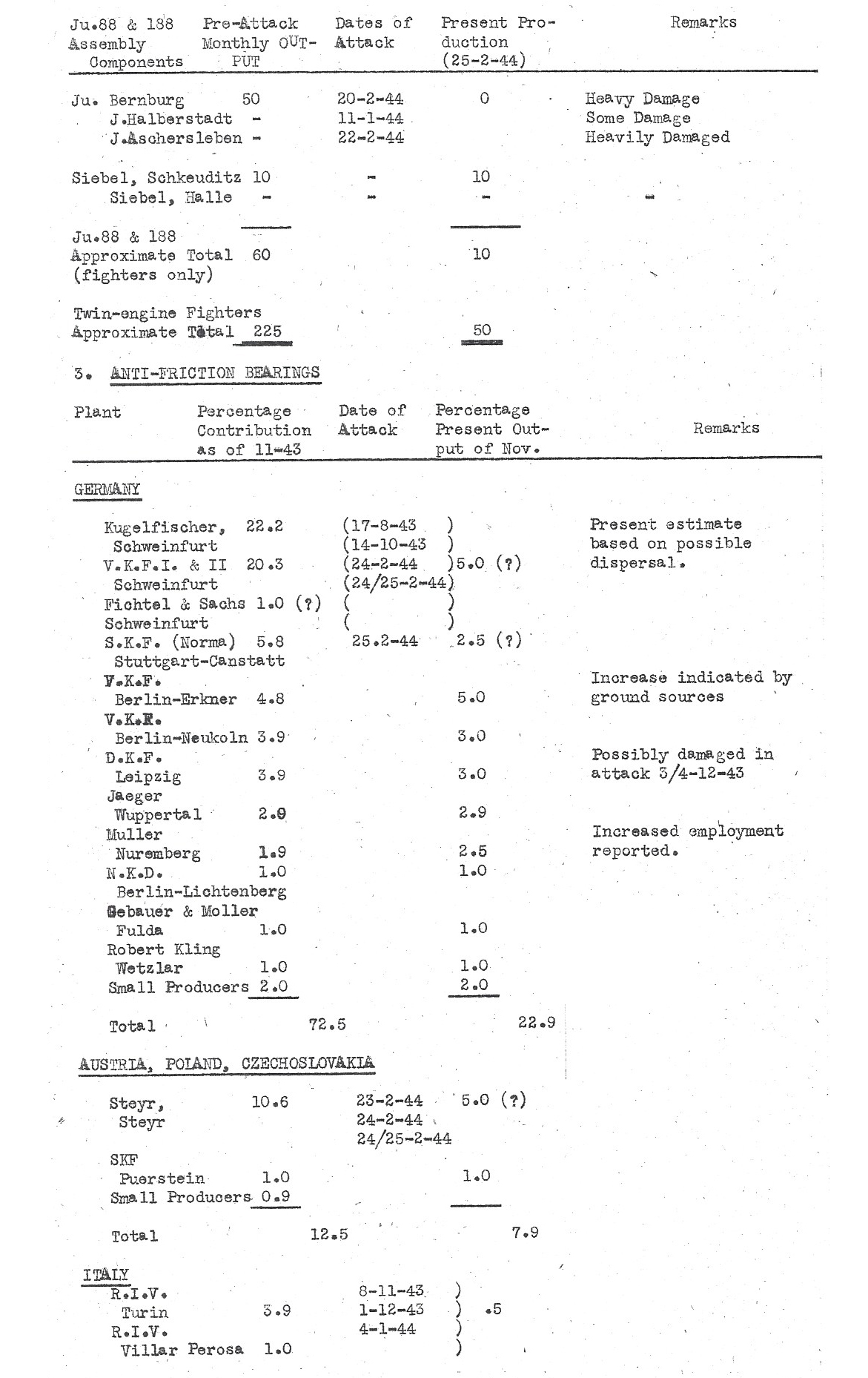

German output of bombers declined in December and January and suffered a further small reduction by the bombing of Rostock, Bernburg and A.T.G. [Allgemeine Transportanlagen-Gesellschaft (General Transportation-Equipment) in Leipzig] in February. A summary of production and repair and their relationship to total strength follows:

These figures are fairly typical of the past months during which monthly bomber production and repair together have represented about 20% of total strength. In other words, the turnover of the bomber force has occurred about once every four or five months. In contrast, before the February raids [Operation ARGUMENT (20 February 1944 – 25 February 1944)] fighters turned over every two and one half to three months.

The part played by repair in the maintenance of the bomber force is more important than for fighters. Monthly input from repairs is about 23% of total new bomber accessions against only 8% in the case of fighters.

2. STRATEGIC RELATION TO OVERLORD AND AFTER

An attack on bomber factories will have some effect on the first-line bomber force before D-Day, but not as great proportionally as the impact of attack on fighters. For one thing, the interval is longer between acceptance of bombers by the GAF and their arrival at first-line units; for another, as outlined above, the rate of turnover is slower and the contribution of repair plants larger.

The strategic importance of reducing the bomber force, has been lessened. The numbers and effectiveness of the bomber force has declined during the past year as the GAF has gone on the defensive; and its effectiveness has declined even more as a result of the attacks against fighter factories [i.e., since the POINTBLANK directive (14 June 1943)]. If fighter support can be cut down by at least 70% with the completion of the campaign against fighter factories, the tactical operations of the GAF bomber force in anticipation of D-Day and thereafter will be limited in the main to night attacks of relatively low efficiency.

-1-

3. TARGETS

The full range of bomber aircraft factories is set forth on the following page, with a rough estimate of current monthly output. Final assembly factories of value as targets consist primarily of:

4. VULNERABILITY

Subassembly and component erection plants containing machine tools, presses, heat treating apparatus, specialized jigs, etc., are highly vulnerable, but as shown in paragraph 3, they are well scattered. Final assembly plants are more concentrated but their recuperation period is little more than one month in contrast to three to six months for sub-assembly and component erection. Neither represents a particularly attractive target. Final assembly plants would probably be preferable because of the consequent more immediate effects on strength at D -Day.

5. PROSPECTIVE DAMAGE AND STRATEGIC EFFECTS

In view of the dispersal of the German bomber industry, the possibilities of recuperation between raids, and the large role played by repairs, it is doubtful whether bomber production and repair could be beaten down to much below 150 from the present 420 per month. This achievement does not seem of sufficient importance, assuming that fighters have been properly dealt with, to warrant diversion from other target systems. With the possible exception of the Do 217, the Ju 88 is the only aircraft that would justify any effort. Ju 88 producers might be included in a system of policing the POINTBLANK list [Due to its relatively high speed, the Ju 88 was often pressed into the fighter role]. Occasional attacks might be made on them by bombers detached from divisions pursuing other systems. Both Dornier and Junkers, however, should be watched for any signs that they are starting to produce fighters, and attacked as soon as such production is under way.

-2-

PART 10

TARGET POTENTIALITIES OF OIL – MARCH 1944

CONCLUSION

The major question regarding oil refineries and synthetic plants as a target system has been whether the number of targets and their depth in Germany permitted attack on the requisite scale. Until the present, it appeared that it was a target system beyond Air Force capabilities. In view of the substantial destruction of German fighter production and the consequent lesser fighter opposition, this job may now be within USSTAF and RAF capabilities. If this be the case, no other target system holds such great promise for hastening German defeat.

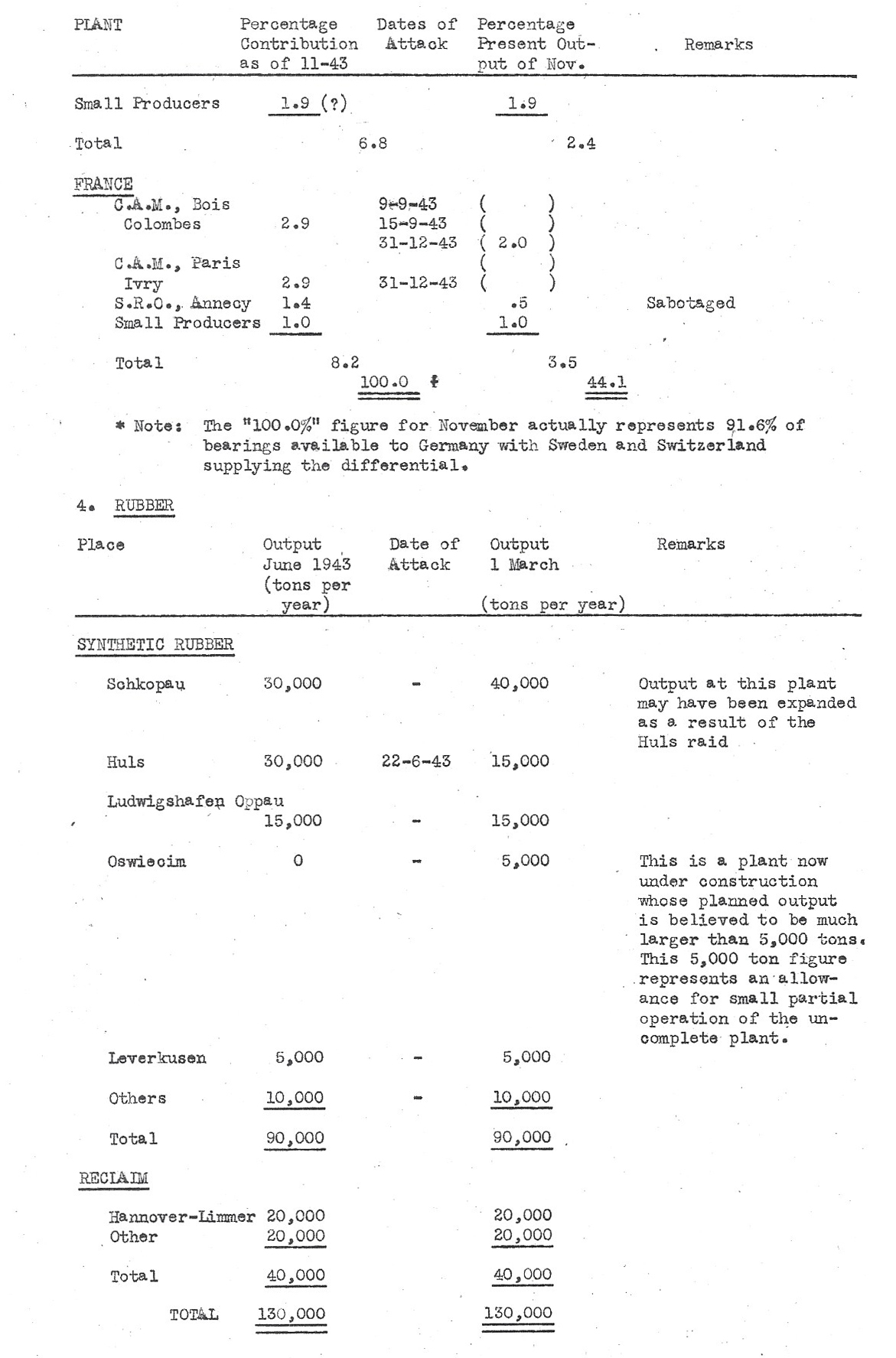

Twenty-three synthetic plants and 31 refineries currently account for over 90 per cent of total Axis refinery and synthetic oil output. 14 synthetic plants and 13 refineries account for over 80% of synthetic production and over 60% of readily usable refining capacity. The effect of attack on these plants would fall more heavily on motor fuel than upon lubricant production, and it would reduce the total current supply of fuel by an estimated 50%.

The loss of approximately 50% of Axis output would directly and materially reduce German military capabilities through reducing tactical and strategic mobility and front-line delivery of supplies, and industrial ability to produce weapons and supplies. The impact in time of these attacks would be hastened by German policy decisions, based on anticipations of their effects.

The extension of attacks to storage facilities in Western Europe might directly impair German mobility in deploying to meet OVERLORD. Indirect benefit to OVERLORD would in any case result from the lessened mobility of German divisions in Finland and Norway, Russia, the Balkans, and Italy.

1. PRODUCTION AND STOCKS

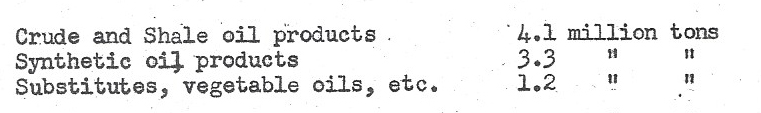

If refineries and synthetic plants are not attacked, it is esti-mated that Axis production of liquid fuels and lubricants during the six months following 1 March 1944 will be 8.6 million tons, comprised as follows:

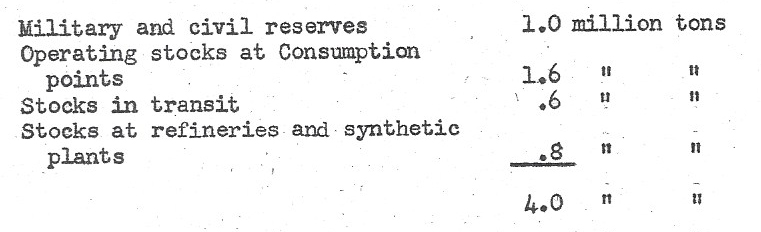

Estimated stocks of finished products at 1 March 1944 aggregate about four million tons, equivalent to about three months output and consumption. These stocks include reserves and the entire distributional pipeline, approximately as follows:

Not all of these stocks could be consumed by the military if output ceased. Some of the stocks at refineries and synthetic plants would be destroyed in bombing. And some of the reserves, operating stocks, and in transit stocks would not be the particular types of products needed (e.g., industrial fuel oil would not satisfy a need for petrol or lubricants.)

Note: Figures on output, consumption, and stocks are taken or interpolated from papers by U.S. Enemy Oil [Committee] and British Hartley Committee

-1-

2. STRATEGIC SIGNIFICANCE OF OIL PRODUCTION

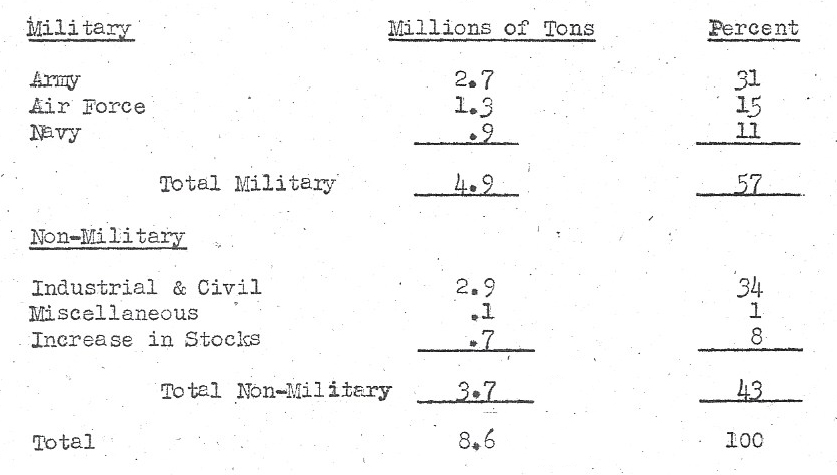

The consumption pattern for the six month period following 1 March 1944, assuming an output of 8.6 million tons, is estimated as follows:

The relevance of oil production for Army, Air Force and Navy operations is clear; as indicated, stocks suitable for military consumption are sufficient for only several months military operations.

Denial of oil supplies to the Axis industry and agriculture would impose very severe economic restriction of an attritional character on the economy. This is not immediately or directly relevant.

The political and morale effects of destroying Germany’s ability to produce oil would be substantial. The will to resist of the German High Command and Wehrmacht, the German political leaders, and the German industrial leaders would be weakened. The will to resist of the German people would be less seriously although they would no doubt regret the disappearance of oil for transportation, food production, power, heat, and industrial requirements.

3. VULNERABILITY

Oil refineries and synthetic oil plants are moderately vulnerable to bomb damage in terms of structure, industrial process, and plant layout. They are large in size, relative to other targets, and would probably require a larger scale of attack than is necessary for, say, aircraft plants. Recuperation time for a severely damaged plant is relatively slow, six months and more.

4. TARGETS

To reduce output in synthetic plants and refineries to virtually zero in the six months following 1 March requires the destruction of 23 synthetic plants (about 3.3 million tons) and 31 refineries (about 3.7 million tons). The capacity of the 31 designated refineries is about 1-1/2 times as large as their output; it is necessary to destroy this excess capacity as well as the capacity in operation. Additional excess capacity in France, Holland and Italy, inconveniently located, might be resorted to by the Germans as an extreme measure. Many are coastal refineries which formerly handled crude oil from ocean tankage. They are located within easy bombing range. A list of the 54 targets involved is attached.

5. EFFECTS

The impairment to German military and industrial capabilities and German morale which would be achieved from actually putting the 23 synthetic plants and the 31 refineries out of action, is very great. If military oil supplies could be totally denied, their resistance to Russian offensives would collapse when stocks. were used up; resistance to OVERLORD

-2-

could be maintained only as long as stocks endured; and GAF air opposition to USAAF and RAF activity would cease with the disappearance of stocks. Destruction of over half as much output, that is, about more than 3.5 million tons in the six months following 1 march would (a) deny to the Axis military forces one-quarter to one-third of their military requirements of about 5 million tons; and (b) reduce industrial and civilian supplies by one half. These effects would be militarily significant, directly through impairing military mobility and front line delivery of supplies, and through affecting industrial ability to produce weapons. The impact in time of these attacks would be hastened by German policy decisions based upon anticipations of their effects. Achievement of much less than half the program, however, would permit the decrease in output to be absorbed by charges in stocks, some decrease in non-military consumption, and insubstantial reductions in military consumption. It would not necessarily have significant direct or indirect military effects.

The destruction of oil production might not affect materially the opening stages of OVERLORD if the Germans choose to allocate stocks to the Western Front. Although if production facilities were destroyed these stocks could probably be profitably attacked as tactical targets, the small volume of oil required for initial OVERLORD operations could not confidently be expected to be denied the Germans.

6. TARGET LISTS

The following tables require a word of explanation.

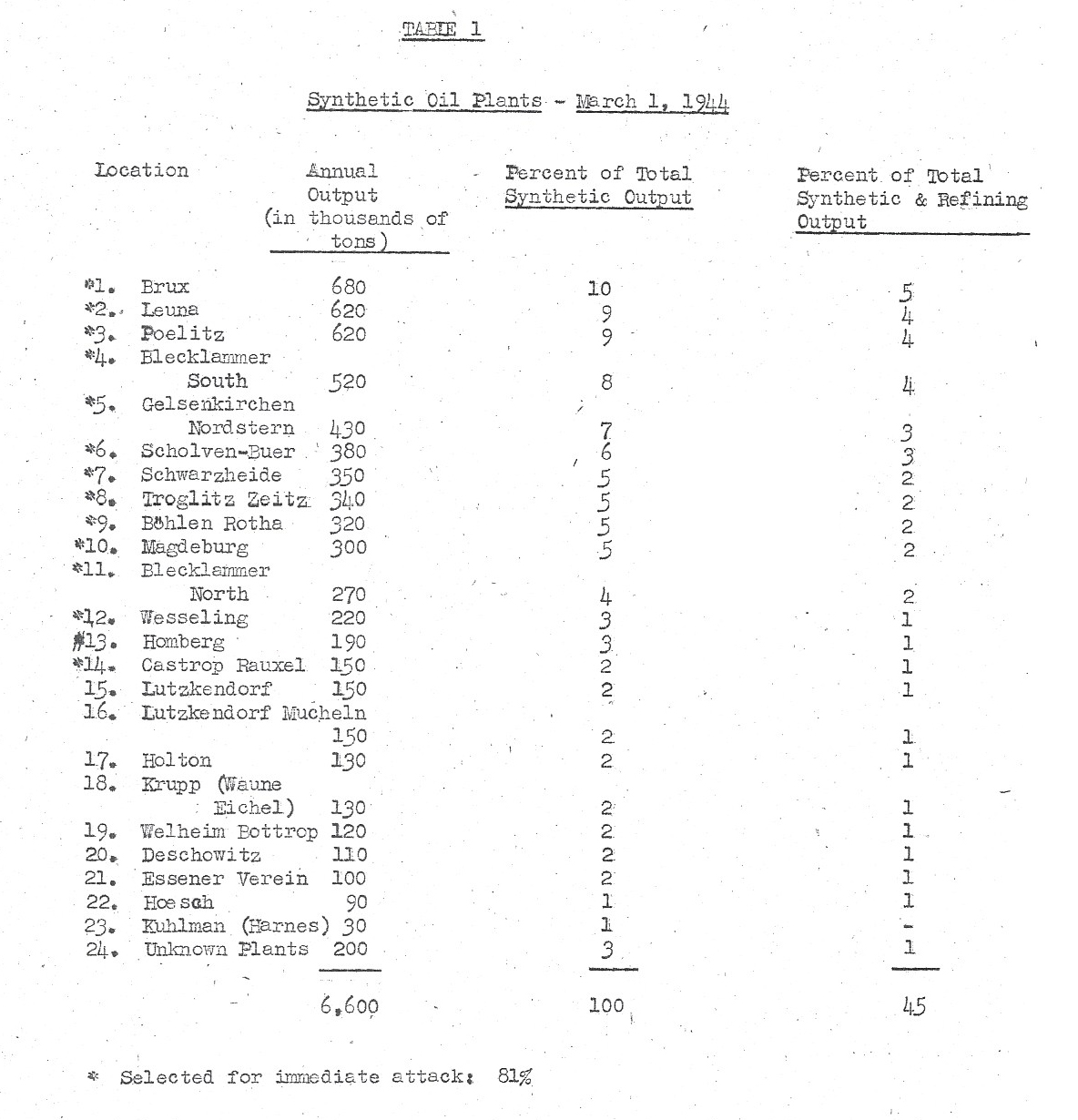

Table 1 presents synthetic oil plants and their output.

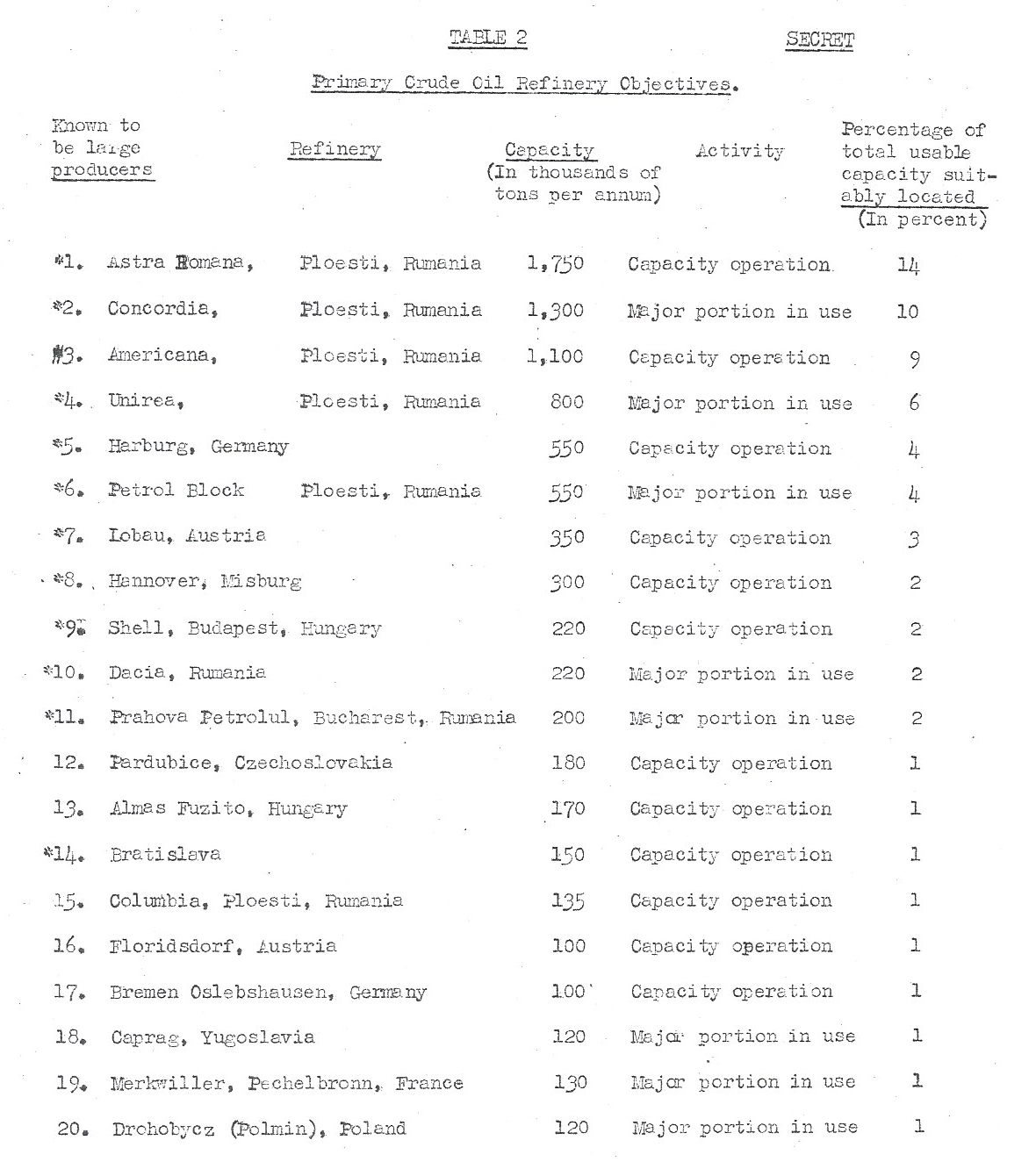

Table 2 includes all Axis refineries capable of handling crude oil which are believed to be operating at more than 60,000 tons per annum. It also includes five large refineries of unknown activity which represent convenient alternative capacity. Table 2, in short, is the list of primary oil objectives in the refining field.

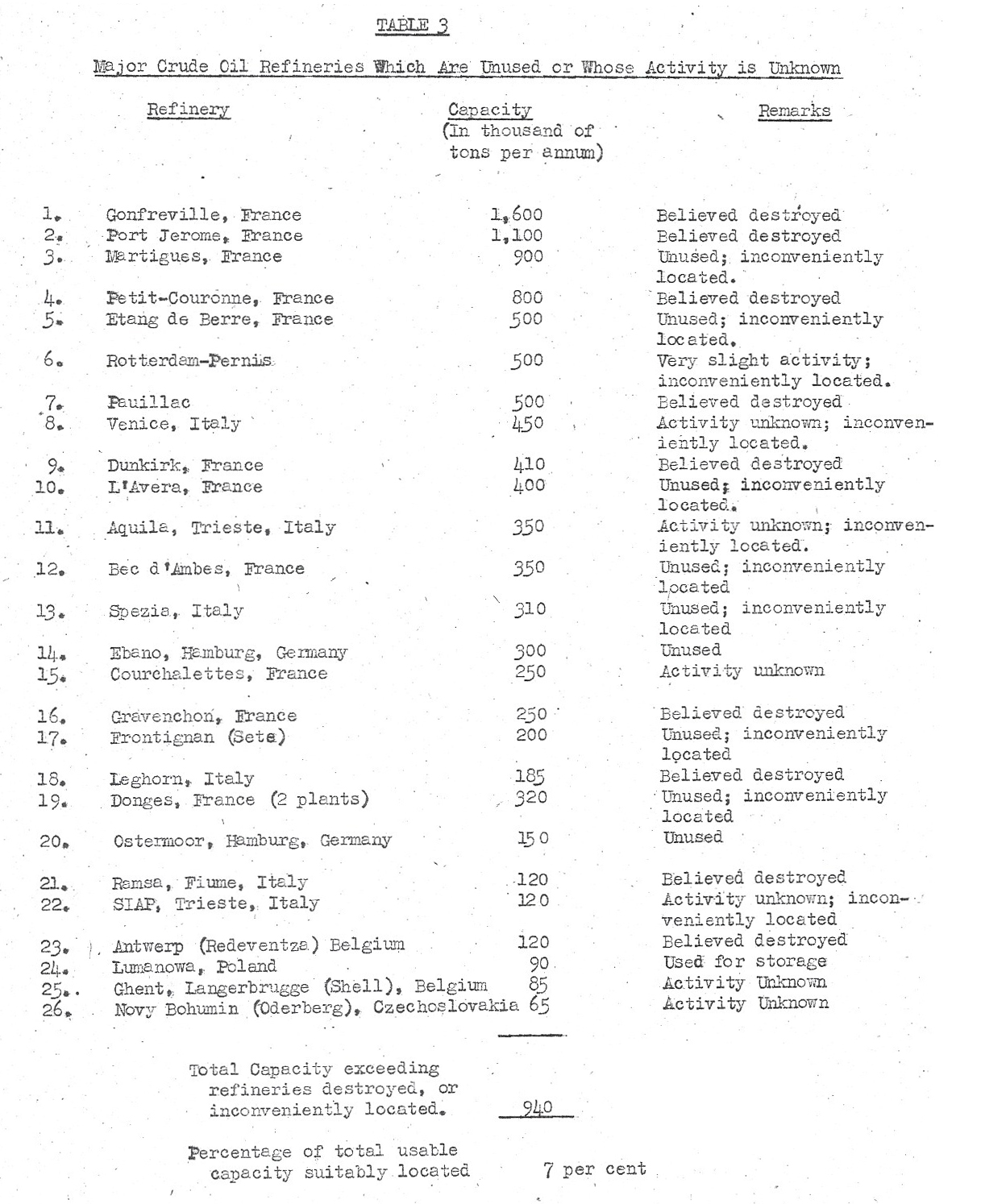

Table 3 lists major refineries not now believed to be engaged in crude oil refining. Some are definitely known to be inoperative and some are believed destroyed or dismantled. The great majority are inconveniently located; German efforts to use them would be an extreme measure. Aerial reconnaissance of these, particularly those for which inactivity is not certain, is essential to prevent major loopholes from arising in the target systems.

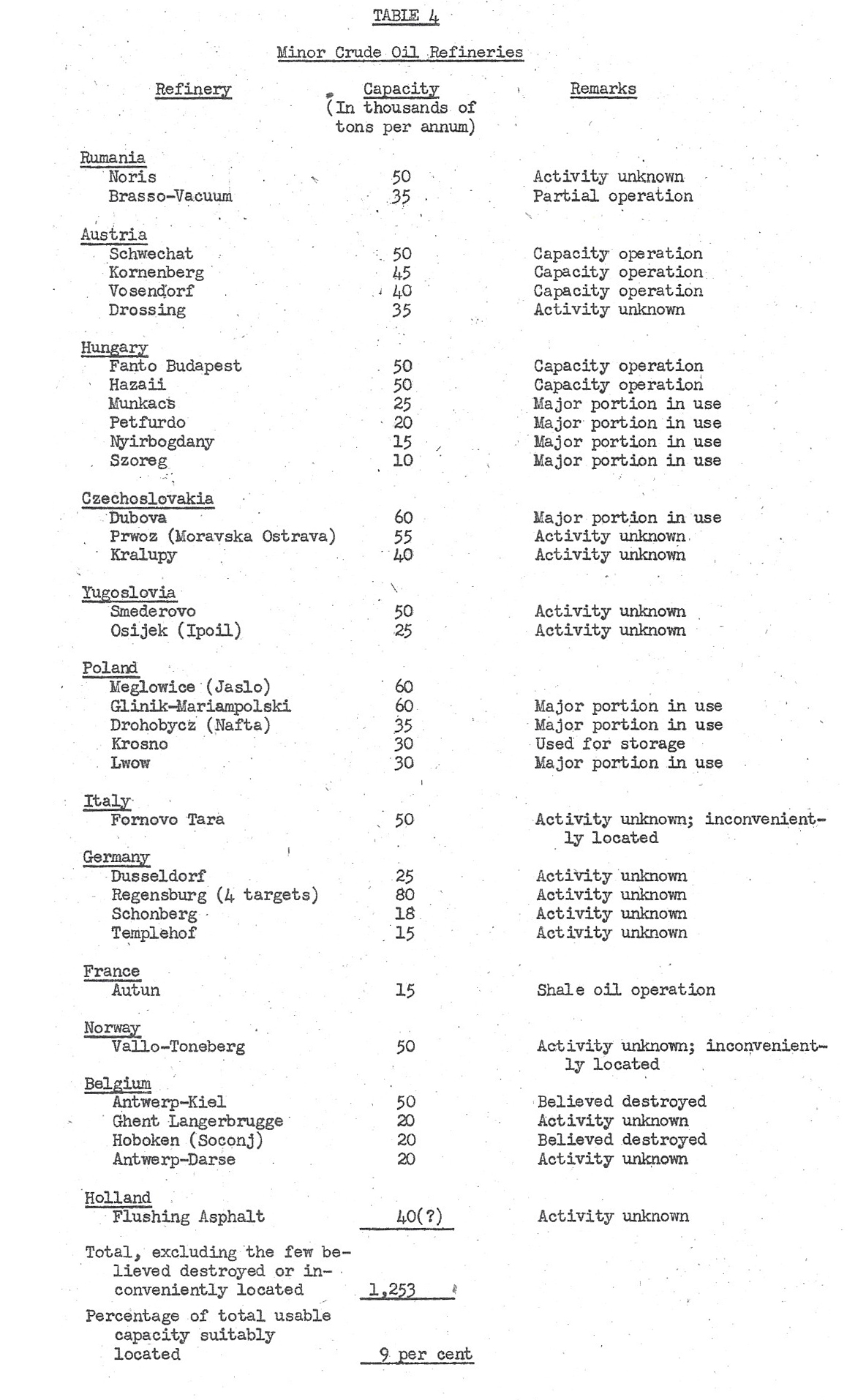

Table 4 lists all other European refineries capable of operating on crude oil. Current information on their activity, which could be improved by aerial reconnaissance, is indicated. Operating plants represent useful secondary objectives or targets of opportunity. The aggregate capacity of these plants is sufficient to refine 14 percent of crude oil output and could represent 8 percent of total oil output. Their attack therefore, is not an essential ingredient of the oil target system.

-3-

-4-

APPENDIX A.

Fighter and Ball Bearing Production.

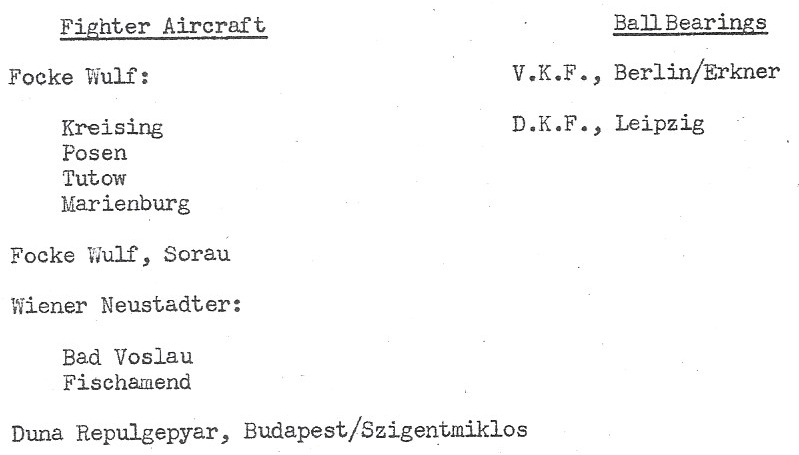

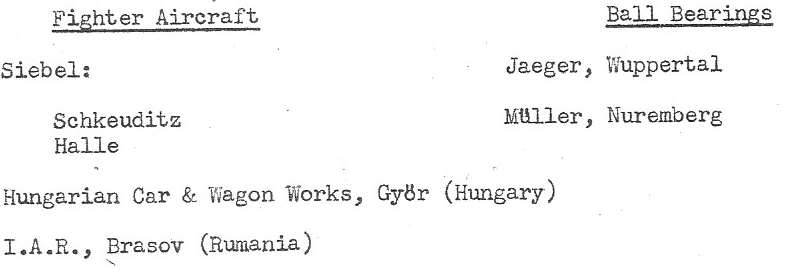

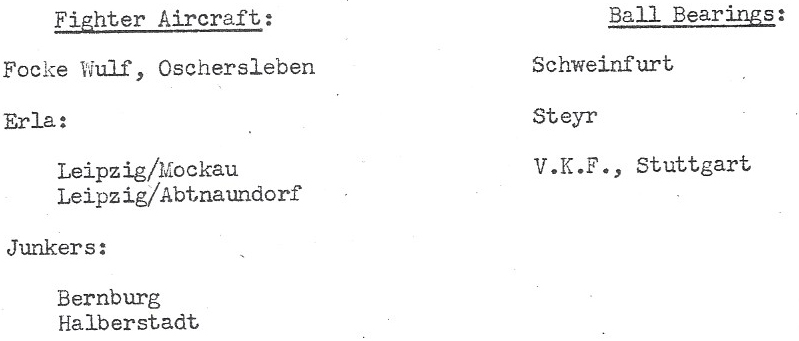

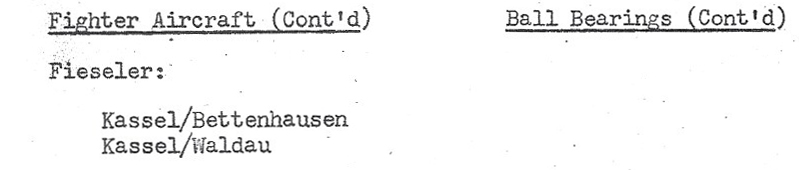

1. Targets which remain in the field of Fighter and Ball Bearing production are of three types:

a. Prime targets, as yet undamaged;

b. Secondary targets, as yet undamaged;

c. Prime targets, partially or wholly out of action.

Group a. above is selected for early attack.

Group b. targets are selected as secondary objectives in the course of missions which have other targets as their primary objective.

Group c. targets will be carefully watched, through photographic and other intelligence, and be promptly reattacked on evidence of effective repair or removal to other sites.

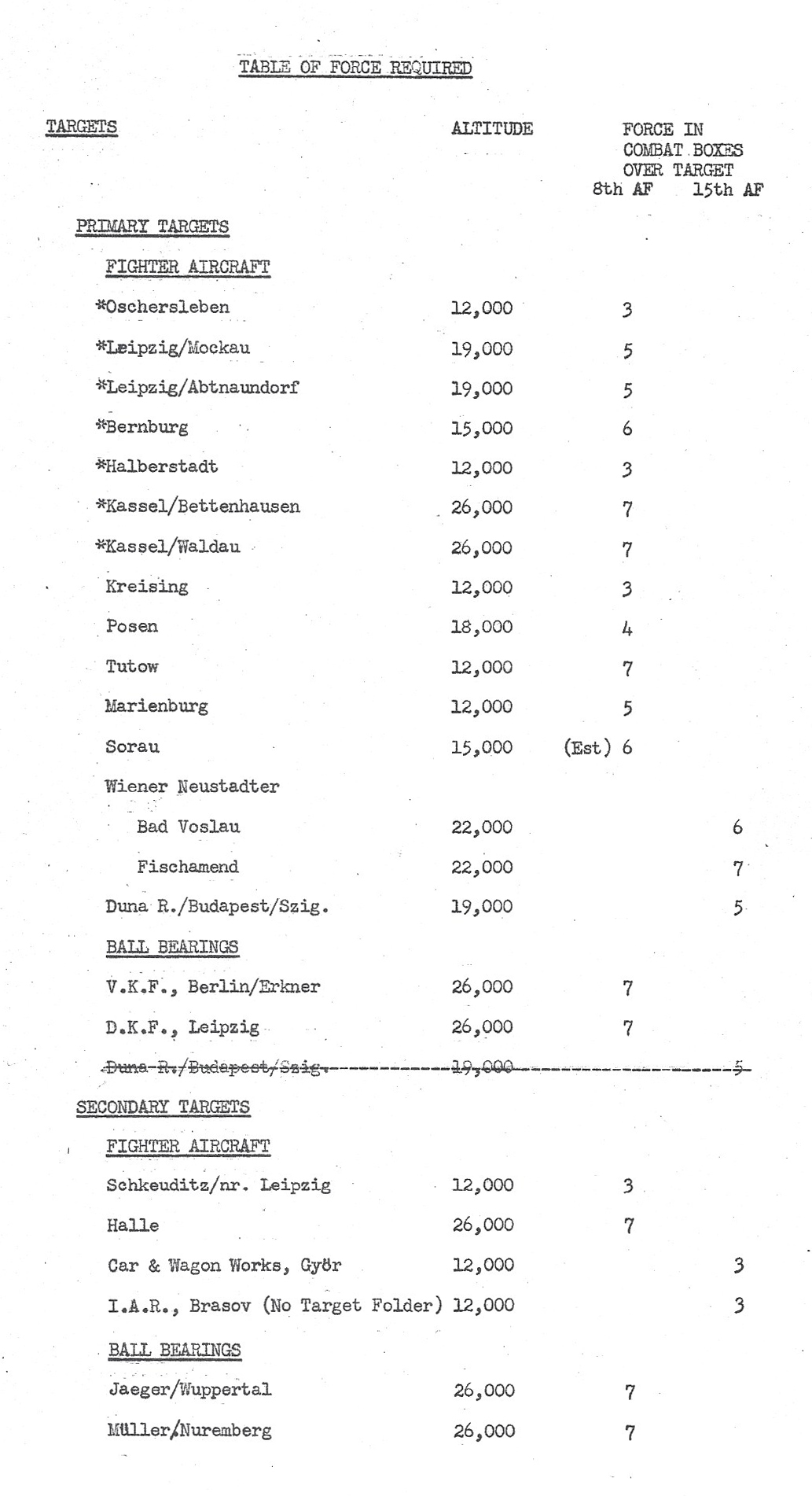

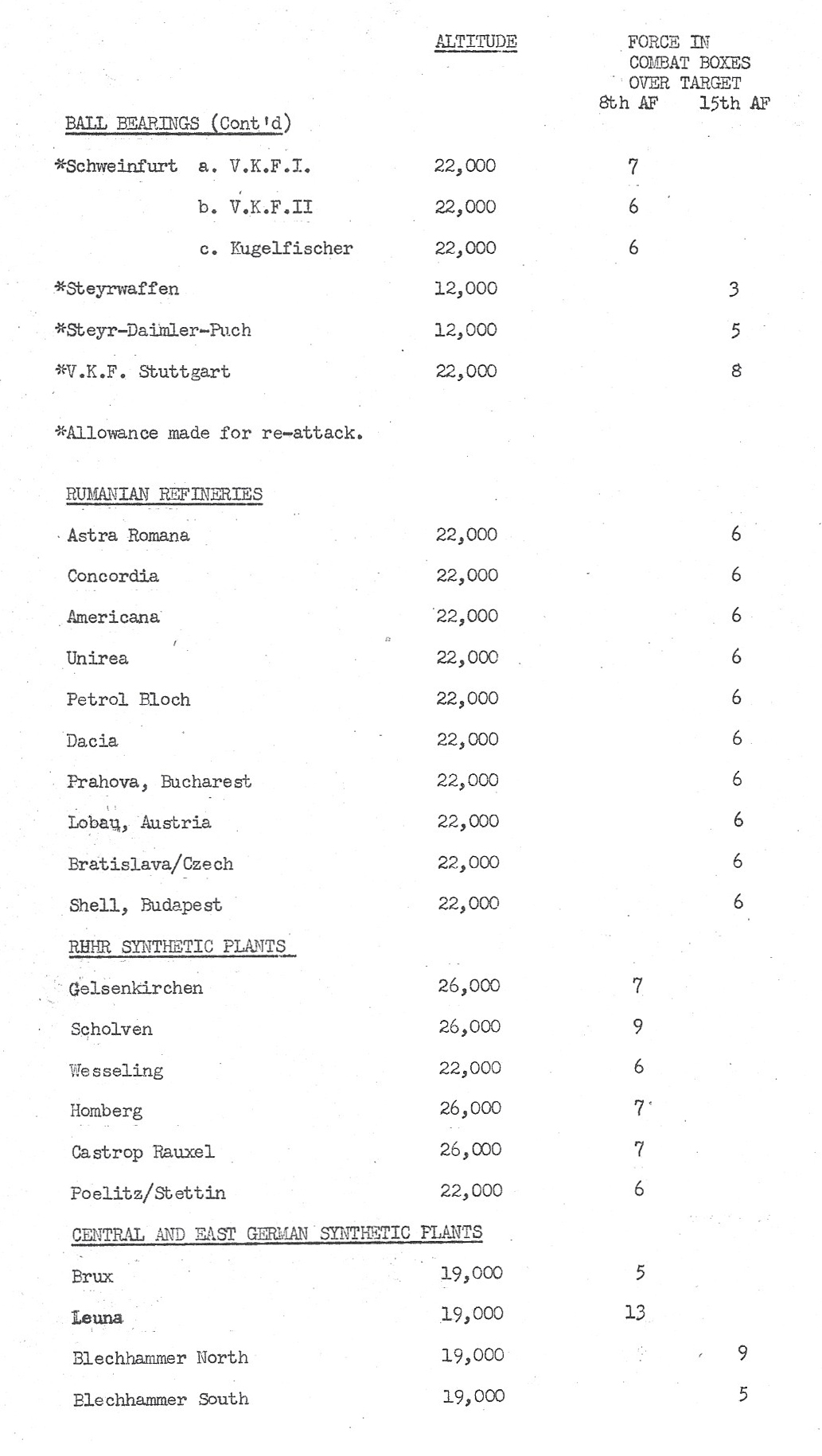

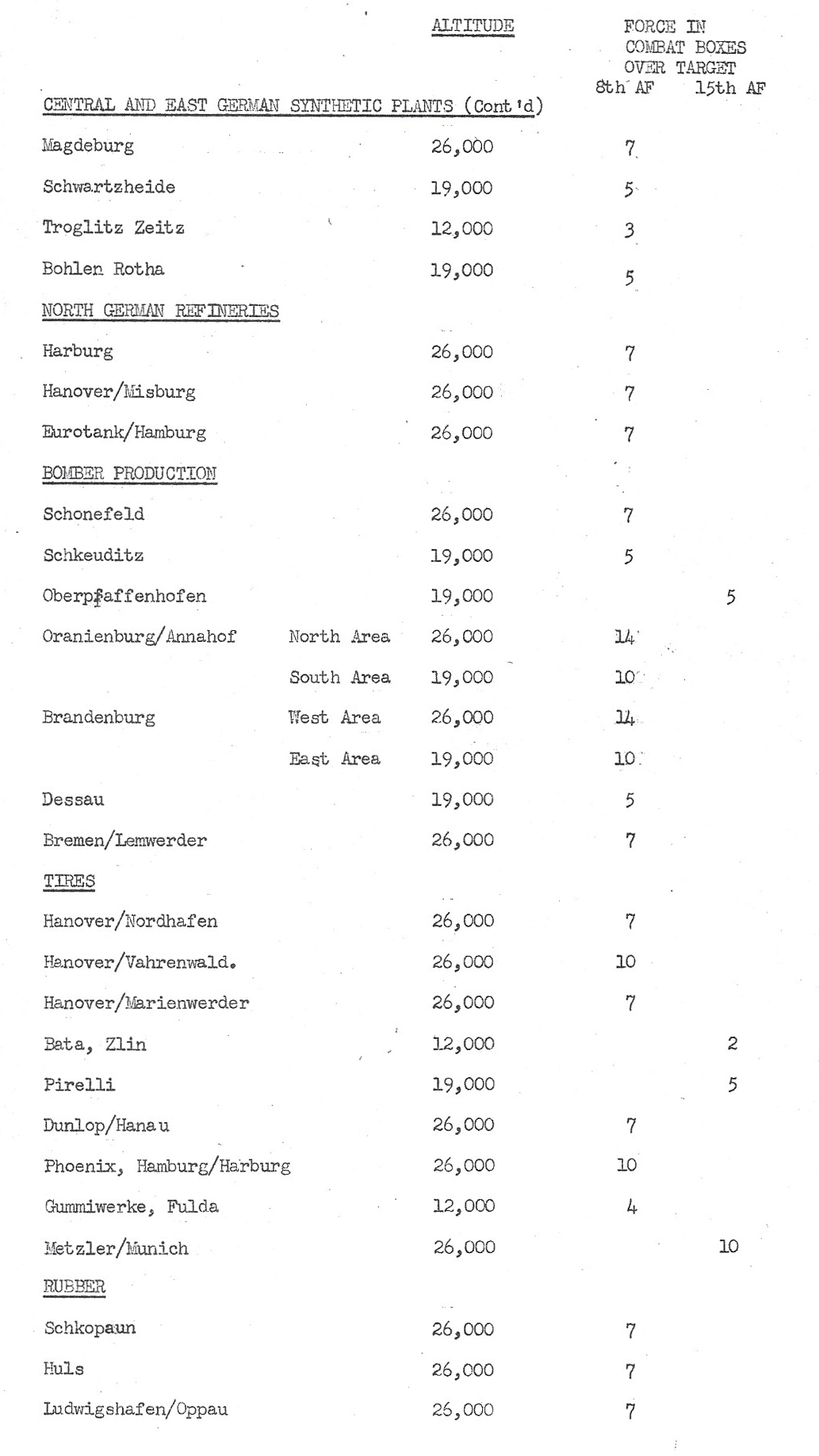

2. The three lists of targets follow:

a. Prime targets, as yet undamaged:

b. Secondary Targets, as yet undamaged:

c. *Prime Targets partially or wholly out of action:

-1-

-1-

*This list will vary with current intelligence.

3. The [successful] execution of this program will have the following effects:

a. It will limit monthly production of Fighters to less than 200 single-engine types, and less than 100 twin-engine types.

b. With that continuing level of production air supremacy is assured: the G.A.F. will be incapable of offering serious opposition to other strategic operations against German targets, or of sustaining large-scale close support operations from D-Day forward.

c. It will limit German ball bearing production to not more than 35 percent of the November 1943 level.

d. With that continuing level of production, a spreading crisis will be imposed on German industry producing aircraft of all types, and on other major forms of finished armaments, as well as upon the G.A.F. and German Army Maintenance Commands.

4. Effort Required:

a. On listed targets:

8th Air Force: 63 Combat Box attacks

15th Air Force: 24 Combat Box attacks [roughly 960 individual aircraft sorties]

b. Reattacks on listed or other targets:

8th Air Force: 55 Combat Box attacks [roughly 1,980 individual aircraft sorties]

15th Air Force: 16 Combat Box attacks [roughly 640 individual aircraft sorties]

Note: For greater detail with respect to the present position of fighter aircraft and ball bearing targets see Appendix F.

-2-

APPENDIX B.

PETROLEUM.

1. Twenty seven major targets in the field of Petroleum production, comprising 14 synthetic plants and 13 refineries, are selected for immediate attack. If surplus effort eventuates, additional targets will be assigned for attack.

2. These targets are listed below by the areas into which they fall:

CENTRAL AND EAST GERMAN SYNTHETIC PLANTS:

Brux

Leuna

Bleckhammer South

Bleckhammer North

Magdeburg

Schwartzheide

Troglitz Zeitz

Bohlen Rotha

RUHR SYNTHETIC PLANTS:

Gelsenkirchen

Scholven

Wesseling

Homberg

Castrop Rauxel

Poelitz/Stettin (Synthetic Plant)

NORTH GERMAN REFINERIES:

Harburg

Hanover/Misburg

Eurotank/Hamburg

RUMANIAN REFINERIES:

Astya Romana, Ploesti

Concordia, Ploesti

Americana, Ploesti

Unirea, Ploesti

Petrol Block, Ploesti

Dacia, Ploesti

Prahova, Bucharest

Lobau, Austria (Refinery)

Bratislava, Czechoslovakia (Refinery)

Shell, Budapest (Refinery)

3. These targets account for more than 80 percent of total synthetic production and 60 percent of usable refinery capacity, suitably located.

4. Successful attack will have the following effect on the German Petroleum position:

a. Current supplies of all petroleum products will be reduced by about 50 percent over the six months beginning with the assault on this system, and the loss will be greater in motor fuel than in lubricants. The result of policy decisions based on the anticipations of these effects will be immediate.

b. A likely form in which the Germans will choose to accept this loss will be the denial to their military forces of about one third of their requirements, and a reduction in essential industrial consumption by about one half.

-1-

c. In order to limit the loss to this extent the Germans will be forced to put into action now-idle refining machinery in Western Europe, where it would be easily accessible to subsequent attack.

d. This reduction of German military and industrial capabilities will have the following effects:

(1) The efficiency and mobility of troops on existing fronts will be impaired; and the ability of the Germans safely to withdraw troops from these fronts to the West will be consequently limited.

(2) This general embarrassment, affecting the capabilities of all ground forces, will be an important factor in the decision of the German High Command to continue resistance after D-Day.

e. This target system offers the maximum opportunity for reducing the defensive capabilities of the German Army by heavy bomber attack outside the immediate tactical area.

5. Effort Required:

Eighth Air Force: 101 Combat Box Attacks.

Fifteenth Air Force: 74 Combat Box Attacks.

Note: For analysis in greater detail see Supplement, Part 10.

-2-

APPENDIX C.

RUBBER AND TIRES

1. Five targets exist in the field of Rubber production; nine major targets exist in the field of Tire production.

2. Rubber production is selected for immediate attack.

3. Tire factories represent an accumulation of Rubber stocks in store and in process of the order of two weeks’ production. Their destruction will hasten the effect on German strength of the attacks on Rubber production, but they are not regarded as a major objective of attack. They are, therefore, selected as secondary objectives, in the course of missions which have other targets as their primary objective.

4. The lists of targets follow:

5. The successful execution of this program will have the following effects:

a. It will limit German Rubber production to about 35,000 tons, or roughly 25 percent of the rate obtaining at 1st March 1944.

b. With that continuing level of production a spreading crisis will be imposed on the German Army which will progressively limit its mobility.

c. The effects of this crisis will be felt from about three months after the beginning of attack, and will reach its climax six to eight months after the attack. The result of policy decisions based on anticipations of these effects will be immediate.

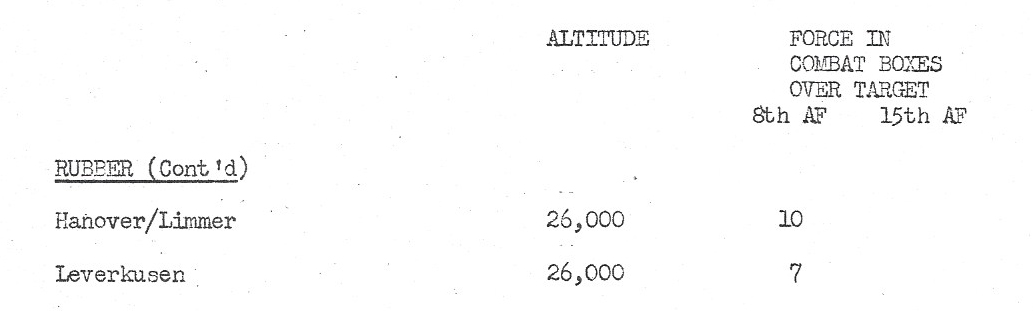

6. Effort Required:

RUBBER

8thForce: 38 Combat Box attacks

15th Air Force: 0 Combat Box attacks

TIRES

8th Air Force: 45 Combat Box attacks

15th Air Force: 17 Combat Box attacks

Note: For a more detailed statement of the position of rubber targets see Appendix F; for analysis in greater detail of the potentialities of the tire system, see Supplement, Part 7.

-1-

APPENDIX D.

1. Seven major bomber assembly plants remain undamaged in Germany. They are the following:

2. These factories and aircraft on the associated airfields, are selected as secondary targets in the course of missions which have other primary objectives.

3. Because of the relatively slow turnover of bombers in first line strength, bomber component factories are not selected for attack, because of the long delay between attack and effects on first line strength.

4. The successful consummation of the attacks will have the following effects:

a. Bomber production will be held to a level of less than 150 per month.

b. At this continuing level of production the German bomber force will be incapable of sustained operations in close support.

c. Sporadic attacks of limited objective will still be within the capabilities of the German bomber force.

5. Effort Required:

8th Air Force: 72 Combat Box attacks

15th Air. Force: 5 Combat Box attacks

Note: For analysis on greater detail see Supplement, Part 9.

-1-

APPENDIX E.

TRANSPORT

1. To effect a 30 percent reduction in German rail traffic over a period of a year, 500 targets must be successfully attacked, of which 250 are major workshops of heavy construction. Since military traffic is not more than one fifth of total German traffic, this series of attacks would have little direct military effect.

2. Consequently, German transport targets have not been selected for systematic attack as primary objectives, prior to the beginning of the direct support period.

3. In order to impose a useful continuing attrition transport centers have been selected as targets of last resort.

4. The present report does not treat the merits of interdiction of transport lines, which constitutes mainly a tactical problem.

NOTE: For analysis in greater detail see Supplement, Part 2.

APPENDIX F.

PRESENT CONDITION OF POINT BLANK SYSTEMS

CONCLUSIONS

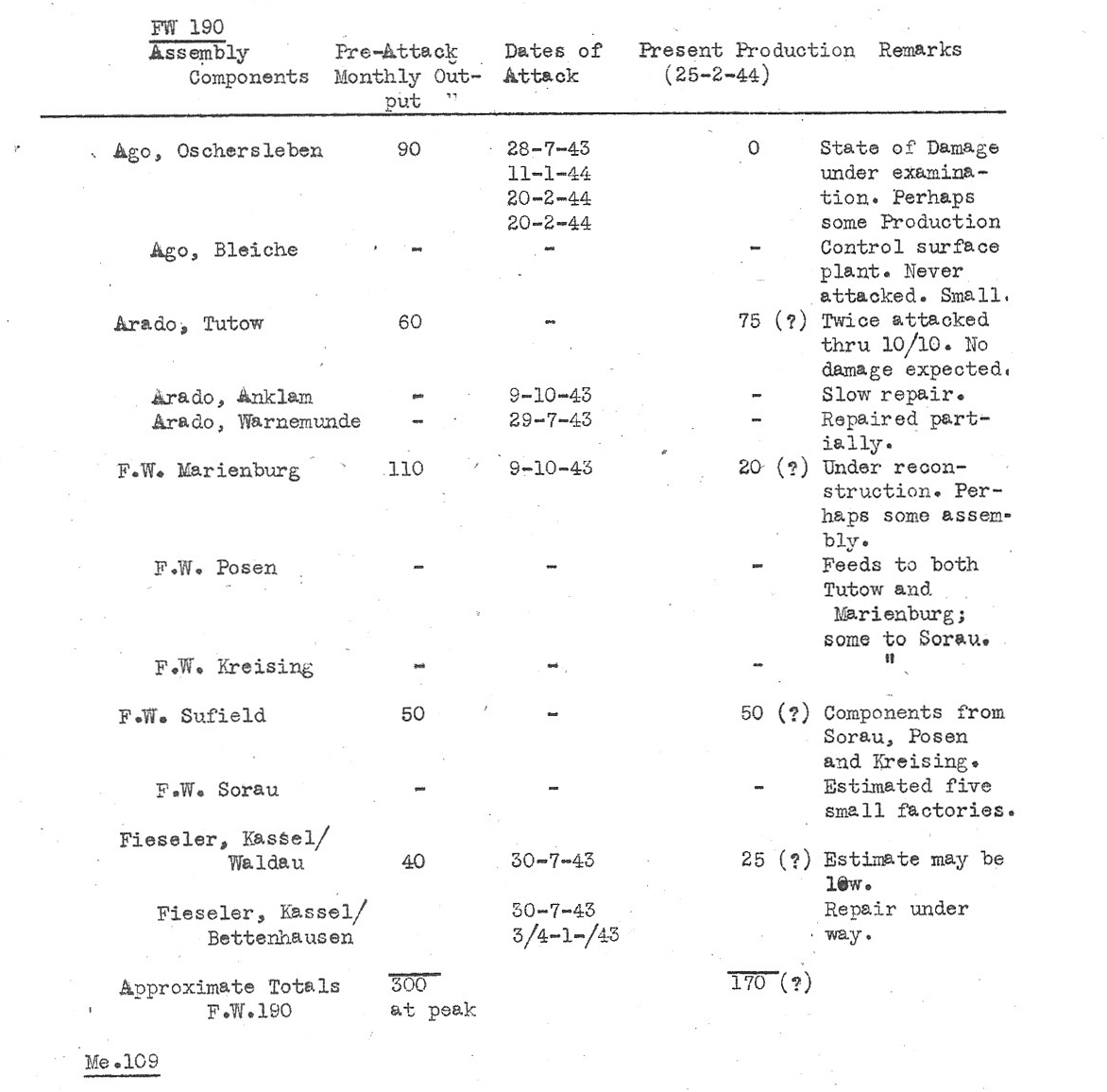

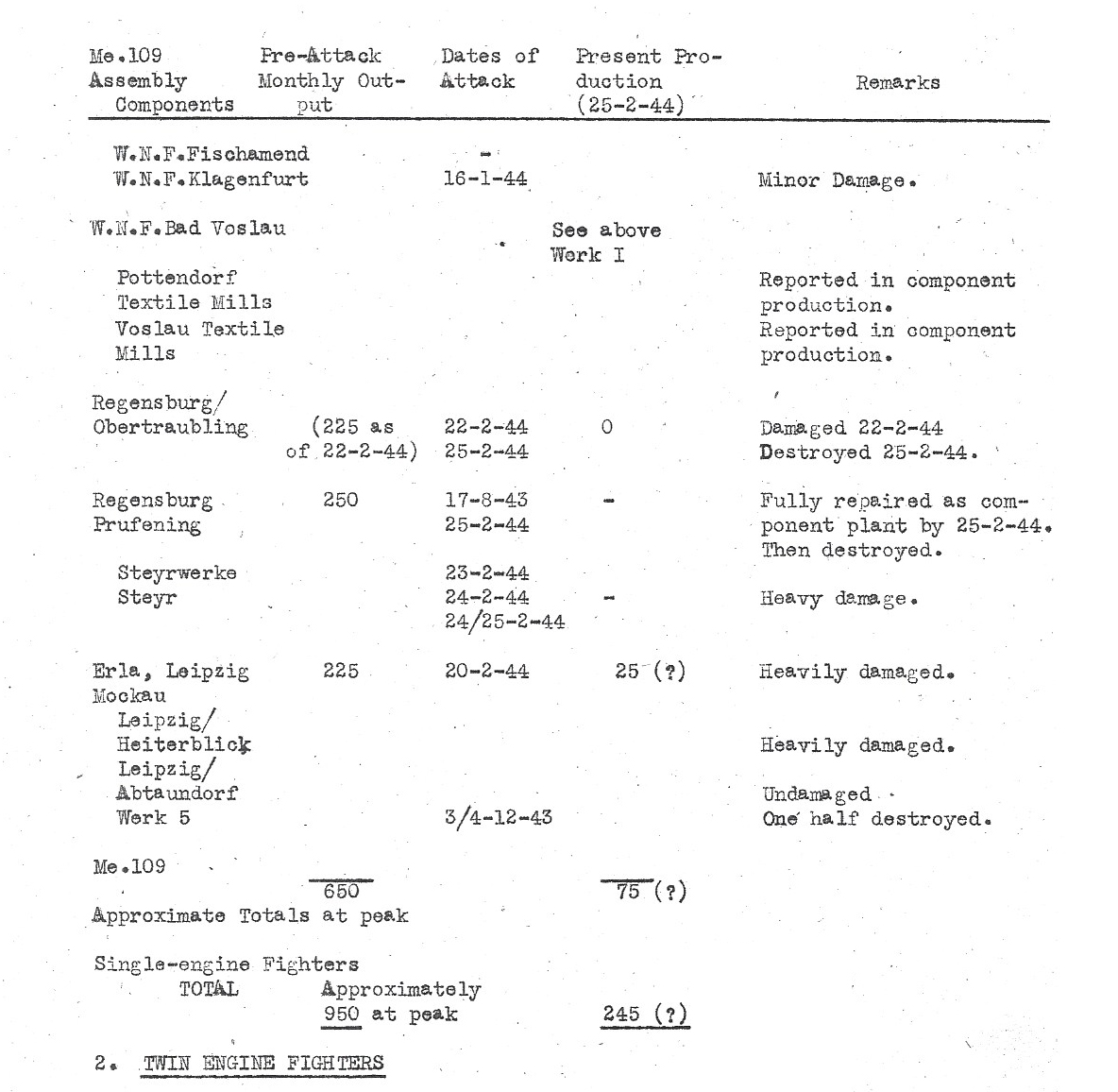

While it is too early to make definitive statements about much of the damage inflicted during the final week of February, it appears that German single-engine fighter production has fallen, by 1 March 1944 to about 250 planes per month, or 25 per cent of pre-raid peaks of production: [twin]-engine fighters to about 50 per month or 22 per cent of pre-raid rates: ball and roller bearing output to 40-50 per cent of November levels; while rubber supplies were still at the same figure.

Attacks have been made on the oil refineries at Ploesti (August 1943) [Operation TIDAL WAVE] and the synthetic oil plant at Gelsenkirchen [bombed on 5 November 1943, though the primary target was the area’s marshaling yards]. Of this date these attacks have probably not weakened the German petroleum position, although the elimination of excess refinery capacity at Ploesti had increased the vulnerability of that complex to subsequent attack.

The tables below summarize present knowledge of the degree of destruction imposed upon fighters, ball bearings and rubber. This information, as noted, is tentative.

1. SINGLE-ENGINE FIGHTERS

-1-

-2-

-3-

-4-

APPENDIX G.

COMPUTATION OF EFFORT

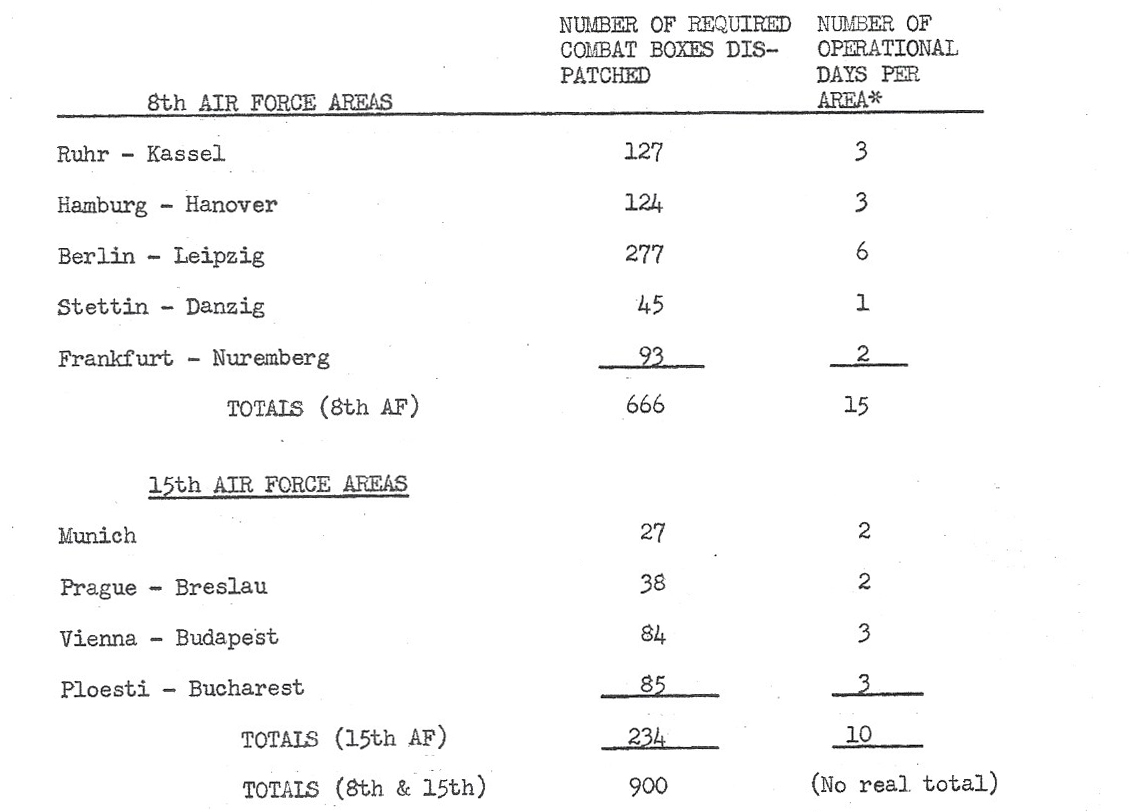

1. As the basis for all calculations finally resulting in the “Table of Force Required” at the end of this Appendix, the experience figures of the Eighth Air Force were used. Since bomb dispersion from various causes is definitely decreasing, this average gives of itself a margin in the calculation; an extra 12-1/2% has been allowed for gross errors. (Also an experience average.) Bomb requirements were interpreted in terms of combat boxes of eighteen (18) planes over the target, thereby allowing for individual aircraft failures to go with their units.

2. The resulting total effort required over the target is 500 combat box attacks in which no allowance has been made for the fact that, on the average, about 44% of the units dispatched do not attack assigned targets. Therefore, the actual effort required must be increased by 400 combat boxes, making a total dispatched effort of 900 combat boxes.

3. Although the figures given in the preceding paragraph give a basis for estimating the capabilities of the two Air Forces involved, they must be interpreted more practically in terms of operational days for different areas as expressed in the following tables:

(All figures include allowance for 44% unit failures to attack assigned targets.)

*Based upon having at least fifty (50) combat boxes available in the 8th Air Force and at least twenty (20) in the 15th Air Force.