Timeline of Strategic Aviation

Second World War

1939-1940

1 March 1939

After four years as CG US GHQAF, MG F. Max Andrews is demoted to COL and made air officer to VIII Corps in San Antonio, TX. Andrews is punished because of a highly-publicized speech he gave to the National Aeronautic Association on 16 January, wherein he labeled the US a “sixth-rate airpower” with less than 400 combat aircraft. The speech was a major embarrassment to Secretary of War Harry H. Woodring (D-KS), who had previously assured the nation about its air strength in the face of European saber-rattling. Andrews is replaced by MG Delos C. Emmons and exiled to the very position that Billy Mitchell was in 1925. The officer Andrews replaces is COL Hugh J. Knerr. Knerr had once been on Andrews's staff but was moved when CSA GEN Malin Craig forced Andrews to purge his staff in February 1938. A final humiliation, Knerr is forced into an early-retirement on trumped-up medical charges. Knerr and Andrews are returned to senior air commands after the outbreak of war.

15 March 1939

Germany annexes the entirety of Czechoslovakia, declaring the newly taken regions to be the Protektorat Böhmen und Mähren (Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia). Having annexed the Sudetenland of Czechoslovakia the previous year, German Führer Adolf Hitler is able to demand Czechoslovakia’s surrender with little resistance because of its now pitiful status. The nation became a fragment of its former size due to the concessions demanded in the Treaty of Munich, resulting in the collapse of its economy and the loss of most of its border fortifications. Overburdened with a refugee crisis of Czechs fleeing regions annexed by Germany and Poland, Czechoslovakia cannot help but fold. Czechoslovakian Prezident Emil D. J. Hácha suffers a heart attack during his meeting with German Führer Adolf Hitler, requiring medical attention to stay conscious long enough to sign his nation's surrender. With Poland refusing to concede to German demands similar to those toward Czechoslovakia, the elimination of Czechoslovakia is a natural prerequisite to an invasion of Poland.

13 April 1939

An exercise held at Fort Benning, GA sees US GHQAF Boeing B-17s and Douglas B-18s bomb a battleship outline 600 ft by 105 ft in size. This demonstration utilizes the new Norden bombsight, with ten out of the twelve bombs dropped directly hitting the target.

A Dutch-Swiss emigree, Carl Norden was originally an engineer with Sperry Gyroscope, whose designed a bombsight whose sighting automatically signaled the Pilot's Directional Indicator (PDI) in 1924. This was upgraded in 1930 with an analog computer design which calculated time-of-drop internally, eliminating the human factor in calculations by having the bombardier merely input variables such as altitude, airspeed, and drift. The success of this new design was immediately evident and Norden was able to set up his own company in 1931. The US Army was also interested. Throughout 19-28 December 1927, the 2BG took part in a highly-publicized exercise to destroy the Pee Dee River Bridge near Albemarle, NC (then marked for an artificial lake), and while the tests brought forth valuable lessons - namely, that 'bombing on the leader' was more effective than bombing in small groups - accuracy was shockingly poor. As such, the Air Corps purchased their first Norden in 1929, with the GHQAF ordering its first production run in 1934. The human factor in keeping the airplane stable is later eliminated with the introduction of all-electric autopilots such as the Sperry A-5 and Honeywell C-1.

Army interest in the sight is bitterly resisted by the Navy, who have legal precedence in Norden procurement. One unintended consequence of this is the damaging of technological relations with Great Britain, who showed great interest in the sight after this day's demonstration is witnessed by a mission led by Sir Henry T. Tizard. Army frustration with this arrangement was such that they turned to Sperry to develop their own computing sight in 1937. This rivalry is finally put to rest 4 August 1943 when the Army standardizes the Norden over the Sperry following the embarrassing revelation that the Navy closed facilities storing surplus Nordens the previous May.

Much of the preference for the Norden over the Sperry is due to the CEO of the Carl L. Norden Co., Ted Barth. While the sight is classified 'top secret' - to the point that photography is prohibited and its operators are required to take loyalty oaths - its existence is nevertheless played up in publicity, famously claiming that the sight is capable of “putting a bomb in a pickle barrel.” The Norden is indeed capable of uncanny accuracy and remains in usage as late as the Vietnam War (1964-1973). However, poor European weather negates the positive results often found in the clear skies of the American West, with an average target error of 1,673 ft complicating the fact that the standard AN-M64 500 lb bomb only leaves, on average, a 20 ft crater.

Norden bombsights are subjected to strict military secrecy, with the sight heads being placed in vaults when not in use. In fact, prospective bombardiers are required to take an oath to its secrecy, being trained to empty their sidearm into the bombsight should they be forced to abandon their aircraft. The oath reads:

Mindful of the secret trust about to be placed in me by my Commander in Chief, the President of the United States, by whose direction I have been chosen for bombardier training, and mindful of the fact that I am to become guardian of one of my country's most priceless military assets, the American bombsight, I do here, in the presence of Almighty God, swear by the Bombardier's Code of Honor to keep inviolate the secrecy of any and all confidential information revealed to me, and further to uphold the honor and integrity of the Army Air Forces, if need be, with my life itself.

14 May 1939

The first flight of the Short Stirling takes place. Inspired by the success of the US Boeing B-17, Great Britain called for its own four-engine bomber in 1936. Short Brothers used their successful Short Sunderland flying boat as a foundation, entering a bid against Supermarine Aviation, who was struggling to stay afloat after the loss of designer Reginald J. Mitchell. Unfortunately, the Stirling is hampered by restrictions from the Air Ministry intended to aid in policing British colonies. These provisions include: capability of catapult-launched takeoff, ability to convert into a 24-person transport, ability to disassemble for rail transport, and a 100 ft wingspan intended to keep the aircraft’s weight down. This last change proved fatal as, while the necessary thickening of the wing makes the bomber surprisingly agile, the resulting low service ceiling makes the aircraft painfully vulnerable to AAA fire. Despite calls from Short to alter the design (the so-called "Super-Stirling"), the introduction of the Avro Lancaster in 1941 negates any further production. By 1943, Stirlings are almost completely relegated to support roles, primarily serving as tugs for glider units. Some 2,371 Short Stirlings are built before being retired in 1946.

No Short Stirlings remain in existence though there is an effort to rebuild one in the UK under the title "The Stirling Project."

| Powerplant: | 4x Bristol Hercules Air-Cooled 14-Cylinder Two-Row |

| 1,929 lb 1,356 hp Supercharged Piston Engines | |

| Armament: | 8x Browning Mk II .303 Caliber MGs |

| Bombload: | 14,000 lbs |

| Cruise Speed: | 200 mph |

| Service Ceiling: | 16,500 ft |

| Range: | 2,330 mi |

15 July 1939

The BLB nasal oxygen mask is standardized for USAAC use on this date. The BLB is the first modern oxygen mask adopted by the US military. Developed by Walter M. Boothby, W. Randolph Lovelace II, and Arthur H. Bulbulian of the Mayo Clinic, the BLB oxygen mask was originally sold earlier that year to airline companies as a means of marketing flights at higher altitudes. While the requirement for oxygen on high-altitude flight was noted from the onset of the Great War, painfully little advance was made until now in the development of an efficient oxygen mask. The BLB mask, with its ridiculous nose piece, uses a continuous flow regulator in conjunction with a high-pressure system. Officially designated the A-7, the BLB is replaced on 1 May 1940 with the A-8, which updates the design to cover the entire mouth. The A-8 and its conjoining system remained in use for much of the Second World War.

Click here to see Northwest Airlines passengers wear the BLB Oxygen Mask.

Also on this date, a special volunteer board, chaired by Mildred Yount (wife of BG Barton K. Yount), selects “The Wild Blue Yonder” from a group of finalists to be the USAAC’s service anthem. Written by CPT Robert M. Crawford, a reservist who tours airshows as “the flying baritone,” the song boldly declares “we’ll live in fame or die in flames, nothing can stop the Army Air Corps!” With a few adjustments, the song remains the service anthem of the current US Air Force.

CPT Robert M. Crawford. A sign of interwar isolationism, US Army officers are discouraged from wearing their uniforms in public.

A pet project of XO USAAC BG Henry H. Arnold, Liberty magazine offered a $1,000 prize (some $19,000 when adjusted for inflation) to the composer whose anthem was selected by the 'senior wives' committee. Crawford's entry was selected over a host of others, including accomplished names like Irving Berlin, and was submitted a mere two days before the deadline. The song is first broadcast on 2 September 1939 at the National Air Races in Cleveland, OH, with Crawford performing the vocals. While written as a march, the gait of the anthem is noticeably lighter than the other services. Likewise, the anthem's bridge section is drastically different in tone from the rest of the song is and is often performed separately. Regularly altered throughout the decades, "Wild Blue Yonder" remains the service anthem of the US's military air arm.

Off we go, into the wild blue yonder, climbing high, into the sun

Here they come, zooming to meet our thunder, at ’em boys, give him the gun

GIVE HIM THE GUN!

Down we dive, spouting out flame from under, off with one hell of a roar

We’ll live in fame or die in flame, hey, nothing can stop the Army Air Corps!

Clear. CLEAR!

Contact. CONTACT!

ZOOM!

Minds of men, fashioned a crate of thunder, sent it high into the blue

Hands of men, blasted the world asunder, how they lived, God only knew

GOD ONLY KNEW!

Souls of men, dreaming of skies to conquer, gave us wings ever to soar

With scouts before and bombers galore, hey, nothing can stop the Army Air Corps!

Here’s a toast, to the host of those who love the vastness of the sky

To a friend we send a message from his brother men who fly

We drink to those who gave their all of old

Then down we roar to score the rainbow’s pot of gold

A toast to the host of men we boast, the Army Air Corps!

Clear. CLEAR!

Contact. CONTACT!

ZOOM!

Off we go, into the wild sky yonder, keep the wings, level and true

If you live, to be a grey haired wonder, keep your nose out of the blue

OUT OF THE BLUE!

Flying men, guarding the nation’s border, we’ll be there, followed by more

In echelon, we carry on, hey, nothing can stop the Army Air Corps!

31 July 1939

Imperial Airway’s Short Empire flying boat Cabot is refueled via a converted Handley Page Harrow tanker as a demonstration over London, UK for its upcoming regular trans-Atlantic service. Mid-air refueling allows the airline to save weight on takeoff by taking on minimal fuel, then topping off said fuel once airborne.

On 24 June 1939, US airline Pan Am inaugurated regular trans-Atlantic service with Boeing 314 Yankee Clipper, the line flying from Baltimore MD to Horta in the Azores, then onto Foyne, Ireland. Pan Am CEO Juan T. Trippe oversaw the meteoric rise of his company via government subsidies to combat incursion of foreign airlines into the western hemisphere. Trippe skillfully expanded this to include a trans-Pacific service (the so-called "China Clipper") and arranged for a trans-Atlantic service by partnering with Britain’s Imperial Airways (soon to be merged with British Airways to form British Overseas Airways Corp. or BOAC).

Lacking aircraft of similar performance, Imperial sought the services of famed test pilot Sir Alan B. Cobham. In 1934 Cobham formed Flight Refueling Ltd., improving upon an in-air refueling technique first developed by Flt Lt Richard L. R. Atcherley. The system worked thusly: the tanker and the receiver aircraft both extended lines, with the tanker line grappling the receiver line upon contact. When this was accomplished, the tanker reeled in the receiver’s line, connected it to the fuel hose, and the hose then reeled into the receiver along the same line. The grappled-line, looped hose system is the first mid-air refueling method to see regular service.

Imperial Airways flies 15 trans-Atlantic crossings using the grappled-line, looped hose system before the outbreak of war brings these flights to a halt.

1 September 1939

Without any formal declaration of war, Germany invades Poland under Operation FALL WEISS (Case White) with five armies divided between Army Groups North (GenObt M. A. F. F. Fedor von Bock) and South (GenObt K. R. Gerd von Rundstedt). Having signed the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact on 23 August 1939, Germany's invasion is joined in the east by the Soviet Union on 17 September, following a declaration that morning from Soviet Minister of Foreign Affairs Vyacheslav M. Molotov that Poland had "ceased to exist." The largest of several nations created in the aftermath of the Great War, Poland was viewed by many in Eastern Europe as an illegitimate nation. The Soviet invasion is composed of seven armies divided between two army groups: Army Group Belarus (Komandarm Mikhail P. Kovalyov) and Army Group Ukraine (Komandarm Semyon K. Timoshenko).

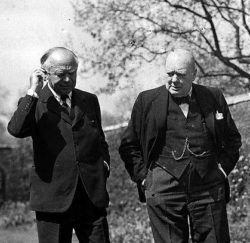

France and Great Britain declare war against Germany on 3 September, honoring the commitments they had made on 31 March. Despite pleas from First Lord of the Admiralty the Rt. Hon. Winston L. Spencer-Churchill (CP) and Secretary of State for War the Rt. Hon. Leslie Hore-Belisha (CP), the British government refuses to declare war against the Soviet Union, arguing that their agreement with Poland was solely in reference to Germany. The European Theater of the Second World War has begun.

Reacting to the German invasion, US Pres. Franklin D. Roosevelt (D-NY) issues a worldwide call “to every Government which may be engaged in hostilities publicly to affirm its determination that its armed forces shall in no event, and under no circumstances, undertake the bombardment from the air of civilian populations or of unfortified cities…” Partially to honor said call and partially to avoid reprisals of greater strength, RAF BC honors this call, constraining its operations solely to maritime strikes, only flying over land to drop propaganda leaflets. Britain’s first act of war sends 18 Handley Page Hampdens and nine Vickers Wellingtons over the English Channel, with a single Bristol Blenheim serving as a spotter, on 3 September. While the Blenheim does spot German vessels, the bomber force never locates them and little more happens this day. It is worth noting, however, that the Blenheim in question, “Q for Queenie” (N6215, 139 Squadron), is the first Allied aircraft of the war to cross the German coast.

I am speaking to you from the Cabinet Room at 10 Downing Street.

This morning the British Ambassador in Berlin [Sir Nevile M. Henderson] handed the German government a final note stating that unless we heard from them by 11 o’clock, that they were prepared at once to withdraw their troops from Poland, a state of war would exist between us.

I have to tell you now that no such undertaking has been received, and that consequently, this country is at war with Germany.

You can imagine what a bitter blow it is to me that all my long struggle to win peace has failed. Yet I cannot believe that there is anything more or anything different that I could have done and that would have been more successful.

Up to the very last it would have been quite possible to have arranged a peaceful and honorable settlement between Germany and Poland, but Hitler [FührerAdolf Hitler] would not have it.

He had evidently made up his mind to attack Poland whatever happened; and although he now says he put forward reasonable proposals which were rejected by the Poles, that is not a true statement.

The proposals were never shown to the Poles nor to us; and though they were announced in the German broadcast on Thursday night, Hitler did not wait to hear comments on them, but ordered his troops to cross the Polish frontier the next morning.

His action shows convincingly that there is no chance of expecting that this man will ever give up his practice of using force to gain his will. He can only be stopped by force, and we and France are today, in fulfillment of our obligations, going to the aid of Poland, who is so bravely resisting this wicked and unprovoked attack upon her people. We have a clear conscience. We have done all that any country could do to establish peace, but the situation in which no word given by Germany’s ruler could be trusted and no people or country could feel itself safe, has become intolerable.

And now that we have resolved to finish it, I know that you will all play your part with calmness and courage.

At such a moment as this the assurances of support which we have received from the Empire are a source of profound encouragement to us.

When I have finished speaking certain detailed announcements will be made on behalf of the Government. Give these your close attention.

The Government have made plans under which it will be possible to carry on the work of the nation in the days of stress and strain that may be ahead. But these plans need your help.

You may be your taking part in the fighting Services or as a volunteer in one of the branches of civil defense. If so you will report for duty in accordance with the instructions you receive.

You may be engaged in work essential to the prosecution of war or the maintenance of the life of the people – in factories, in transport, in public utility concerns, or in the supply of other necessaries of life. If so, it is of vital importance that you should carry on with your jobs.

Now may God bless you all and may He defend the right. For it is evil things that we shall be fighting against – brute force, bad faith, injustice, oppression, and persecution – and against them I am certain that the right will prevail.

4 September 1939

RAF BC launches 15 Bristol Blenheims and 14 Vickers Wellingtons against the battlecruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, the heavy cruiser Admiral Scheer, and the light cruiser Emden near Brunsbüttel, Germany. Avoiding the targeting of civilians and prohibited from using bases in France, Belgium, and the Netherlands, RAF BC focuses its initial strategy on naval targets (provided they are not in port). Having failed to locate any ships the previous day, this day’s strike sees the RAF’s first aerial engagement of the war. The four squadrons are intercepted by Bf-109s of JG77, with Fwl Hans Troitsch making the first aerial victory of the Western bombing campaign: Vickers Wellington "H for Harry" (L4275, 9 Squadron). Other firsts include the RAF’s first loss, a Bristol Blenheim (N6184, 107 Squadron) shot down by AAA fire, and the RAF’s first POW (Flt Sgt George Booth). The strike reveals serious deficiencies within the RAF as bombers are launched haphazardly with inadequate loads and malfunctioning equipment; worse, pitifully few pilots have experience in formation flight. Bombing operations are halted for a period afterwards, resuming on 29 September. This halt does not affect RAF BC's other operations, which primarily entail dropping propaganda leaflets over German cities, with the first flight over Berlin taking place on 1 October.

| Bombers Launched: | 29 |

| Bombers Effective: | 19 |

| Bombers MIA: | 7 |

| Bombers Abort: | 10 |

| Abort Rate: | 34% |

| Loss Rate: | 37% |

| Aircraft Type | Serial No. | Code | Unit |

| Bristol Blenheim Mk. IV | M6184 | unk | 107 Squadron |

| Bristol Blenheim Mk. IV | N6188 | unk | 107 Squadron |

| Bristol Blenheim Mk. IV | N6189 | unk | 107 Squadron |

| Bristol Blenheim Mk. IV | N6240 | unk | 107 Squadron |

| Bristol Blenheim Mk. IV | N6199 | unk | 110 Squadron |

| Vickers Wellington Mk. I | L4275 | H | 9 Squadron |

| Vickers Wellington Mk. I | L4268 | unk | 9 Squadron |

29 September 1939

Motivated in part by the fall of Warsaw, Poland that morning, RAF BC launches 11 Handley Page Hampdens on a patrol over Heligoland Bight. As a result of the long periods wasted in having bomber strikes respond to reconnaissance reports, RAF BC’s strategy launches bombers as reconnaissance-in-force over the English Channel. Half of the force makes a failed attempt to strike a pair of destroyers due to heavy AAA while the other half is never seen again; German radio broadcasts later confirm that interceptors were responsible for the destruction of the second force.

| Bombers Launched: | 11 |

| Bombers Effective: | 6 |

| Bombers MIA: | 5 |

| Bombers Abort: | 5 |

| Abort Rate: | 45% |

| Loss Rate: | 64% |

| Aircraft Type | Serial No. | Code | Unit |

| Handley Page Hampden Mk. I | L4121 | unk | 144 Squadron |

| Handley Page Hampden Mk. I | L4126 | unk | 144 Squadron |

| Handley Page Hampden Mk. I | L4127 | unk | 144 Squadron |

| Handley Page Hampden Mk. I | L4132 | unk | 144 Squadron |

| Handley Page Hampden Mk. I | L4134 | unk | 144 Squadron |

25 October 1939

The first flight of the Handley-Page Halifax takes place. Like the Short Stirling, the Halifax is designed to meet a call from the Air Ministry for a bomber capable of operating throughout the British Empire, but in the more traditional twin-engine format. Competing against the A.V. Roe (Avro) Manchester and Vickers-Armstrong Warwick (a variant of the Vickers Wellington), the Halifax is aided by a later Air Ministry allowance for a four-engine redesign. Teething problems with the new Rolls-Royce Vulture, the engine used in the competing aircraft, suggested quadrupling the older Rolls-Royce Merlin was the safer option (later Halifax variants use the powerful Bristol Hercules radial engine). While the Halifax later becomes an effective bomber, it ultimately falls out of favor with the ascension of Air Mshl Arthur T. Harris to the CINC RAF BC in 1942. The reason is the aircraft's bombbay. Despite the Halifax and Stirling boasting massive bombbays by contemporary standards (13,000 lbs and 14,000 lbs compared to the Boeing B-17’s 6,000 lbs), the design of the two is such that they cannot carry the popular 4,000 lb “blockbuster” bomb. Nevertheless, 6,176 Halifaxes are built, serving RAF Bomber and Coastal Command with distinction, with the last Halifaxes being retired in 1962.

Only two fully-restored Handley Page Halifaxes currently exist, with one example on display at the Yorkshire Air Museum in Elvington, UK and the other on display at the National Air Force Museum of Canada in Trenton, ON.

| Handley Page Halifax Mk. II | |

| Powerplant: | 4x Rolls-Royce Merlin V-1650 Liquid-Cooled 12-Cylinder |

| 1,645 lb 1,315 hp Supercharged Piston Engines | |

| Armament: | 8x Browning Mk II .303 Caliber MGs |

| Bombload: | 13,000 lbs |

| Cruise Speed: | 205 mph |

| Service Ceiling: | 21,000 ft |

| Range: | 1,660 mi |

| Handley Page Halifax Mk. III | |

| Powerplant: | 4x Bristol Hercules Air-Cooled 14-Cylinder Two-Row |

| 1,929 lb 1,356 hp Supercharged Piston Engines | |

| Armament: | 8x Browning Mk II .303 Caliber MGs |

| Bombload: | 13,000 lbs |

| Cruise Speed: | 215 mph |

| Service Ceiling: | 24,000 ft |

| Range: | 1,860 mi |

4 November 1939

Capt Hector Boyes, Royal Navy Attaché to the British Embassy is Olso, Norway, receives a letter from an anonymous German scientist offering technical information. The letter instructs the BBC World Service to open its German language segment with the phrase "Hullo, hier ist London" (Hello, this is London) if the offer is accepted. The instructions are followed and a week later a package arrives with a vacuum tube from an experimental proximity fuse, several rough drawings, and a seven page letter signed, "a German scientist, who is on your side." This report becomes known throughout British intelligence as the Oslo Report.

The report is, in fact, authored by physicist Hans F. Mayer, who is later arrested for criticism of the Nazi government and placed into Dachau concentration camp (surviving thanks to the aid of fellow scientist Johannes Plendl). Mayer's report is so extraordinary that it is at first met with disbelief, the concern being that it may be a plant. The report covers German development of Ju-88 bombers, glide bombs, aerial drones, guided missiles, long and short range radar, blind-bombing systems, acoustic and magnetic torpedoes, and anti-aircraft proximity fuses. Assistant Director of Intelligence (Science) Reginald V. Jones lobbies for the report's authenticity on the basis that Mayer's description of Radio Direction Finding (RDF) equipment closely resembles that under British development. This proves to be a smart move, as the report's details on German radar and blind-bombing capabilities later prove invaluable.

3 December 1939

RAF BC launches 24 Vickers Wellingtons on a reconnaissance-in-force, sinking the minesweeper M1407 and severely damaging the minelayer Brummer. While the attack is not a complete success – the bombs do not detonate, they simply pierce the hull – the mission does see the first successful use of powered gun turrets in combat. LCpl John J. Copley, tail gunner on "Z for Zebra" (N2879, 38 Squadron), manages to shoot down a Bf-110C (ZG26) piloted by future ace Lt Günther Specht (who loses an eye). No bombers are lost on the mission and British and American airmen take strong notice of the turrets' effectiveness, with both countries calling for further development in such systems.

| Bombers Launched: | 24 |

| E/A Destroyed: | 1 |

18 December 1939

Spurred by news that the heavy cruiser Admiral Graf Spree was scuttled near Uruguay that morning, RAF BC launches 24 Vickers Wellingtons on a reconnaissance-in-force near Heligoland Bight. Postwar accounts from both sides recognize this event as the first major air battle of the Second World War.

The flight is a disaster. The route is poorly conceived and formation discipline inadequate; in fact, of the three squadrons involved, the one that holds its formation this day (149 Squadron) escapes with minimal losses. In truth, RAF formation doctrine is unclear and contradictory, stressing the importance of tight formations for mutual protection but advising against any "unwieldy" formation of more than 12 aircraft. Formation training is lacking because the greater concern is AAA-fire, with losses to German interceptors often being dismissed because so many bombers lacked powered turrets. As such, great faith is placed in the Wellington, the only frontline bomber with a powered turret. German interceptors are however by this time familiar with the Wellington's armament, avoiding rear-attacks and now attacking across the beam. Since the bombers lack self-sealing fuel tanks, the Wellingtons prove frightfully flammable and the heavily-armed Bf-110, in particular, proves an effective bomber-destroyer.

This day also sees the first use of German early-warning radar (code-named FREYA), which gives German interceptors an eight minute warning of the British attack. Despite an easily avoidable delay which allows the British to hit their targets prior to interception, the success of FREYA is readily apparent and eleven radar stations are erected in Western Germany by the spring of 1940 (not including those in occupied-France). In the wake of a publicity fallout, CINC RAF BC Air Mshl Edgar R. Ludlow-Hewitt oversees the transition of bomber units to night operations in the following weeks, a policy which RAF doctrine is designed to easily accommodate. By contrast, the Luftwaffe begins to become somewhat complacent with its day-fighter force, progressing little in regard to tactics and equipment until the beginning of the US offensive in 1942.

| Bombers Launched: | 24 |

| Bombers MIA: | 12 |

| Loss Rate: | 50% |

| E/A Destroyed: | 2 |

| Aircraft Type | Serial No. | Code | Unit |

| Vickers Wellington Mk. IA | N2939 | H | 9 Squadron |

| Vickers Wellington Mk. IA | N2872 | unk | 9 Squadron |

| Vickers Wellington Mk. IA | N2940 | unk | 9 Squadron |

| Vickers Wellington Mk. IA | N2941 | unk | 9 Squadron |

| Vickers Wellington Mk. IA | N2983 | unk | 9 Squadron |

| Vickers Wellington Mk. IA | N2888 | A | 37 Squadron |

| Vickers Wellington Mk. IA | N2904 | B | 37 Squadron |

| Vickers Wellington Mk. IA | N2935 | H | 37 Squadron |

| Vickers Wellington Mk. IA | N2936 | J | 37 Squadron |

| Vickers Wellington Mk. IA | N2889 | P | 37 Squadron |

| Vickers Wellington Mk. IA | N2962 | B | 149 Squadron |

| Vickers Wellington Mk. IA | N2961 | P | 149 Squadron |

29 December 1939

The first flight of the Consolidated B-24 takes place. The origins of the B-24 lay in a call for Consolidated Aircraft to produce the Boeing B-17 under license. Under former Army test-pilot Rueben H. Fleet, Consolidated (the merged companies of Gallaudet, Dayton-Wright, and Thomas-Morse) had a reputation for success with large flying boats, making them a natural selection for contracting the B-17. Fleet, however, demurred, instead offering to design their own bomber, using a wing recently developed by David R. Davis. These early aircraft, destined for France and Great Britain under Lend-Lease, are designated LB-30s.

The Davis wing is something of a double-edged sword. The wing features a short-chord and high aspect-ratio, giving the bomber massive amounts of lift at low angles-of-attack. Combining this wing with a low-slung fuselage, the B-24 is capable of carrying a slightly heavier bombload than the B-17 at a much greater distance. Unfortunately, the B-24 suffers from a lower service ceiling and greater fragility, the wings and dual bombbay being prone to structural failure in emergency situations. Likewise, the B-24 is an unforgiving aircraft to control, and it is because of these faults that the US 8AF, in particular, consistently stave off retiring the older B-17.

Later licensing the bomber through Douglas and North American Aviation, it is Consolidated’s partnership with Ford that sees the company implement assembly-line production on an unprecedented scale. The B-24 becomes the most mass-produced multi-engine aircraft in history, with Ford’s Willow Run plant of Ypsilanti, MI, for example, producing at its peak another B-24 every 63 mins. Some 19,256 B-24s are produced prior to retirement at war's end, with the bomber seeing service in every combat theater. B-24s see particular success as a naval patrol aircraft, and in 1944 a specified variant called the PB4Y-2 Privateer enters USN service. While the PB4Y-2 lacks turbochargers, it does include a vertical tail to improve handling, and some 739 PB4Y-2s are produced prior to retirement in 1958.

Despite its widespread use in wartime, surprisingly few Consolidated B-24 Liberators still exist. Perhaps the most complete example – and the only complete example of a D model – is Strawberry Bitch (42-72843, 376BG) currently on display at the National Museum of the US Air Force in Dayton, OH. While this aircraft is overwhelmingly complete, its interior was unfortunately repainted with inaccurate colors in the 1990s. Despite claims that there are three airworthy examples of B-24s, in actuality there is just one: B-24J 44-44052, currently in the colors of Witchcraft (44-44052, 467BG). Like Strawberry Bitch, Witchcraft’s colors are wholly inaccurate, though it is a surprisingly complete example, with functioning radios and ball turret. In regard to surviving PB4Y-2 Privateers, only one example has been restored to wartime condition: BuNo 59819, currently on display at the Pima Air and Space Museum in Tucson, AZ.

| Powerplant: | 4x Pratt & Whitney R-1830 Air-Cooled 14-Cylinder Two-Row |

| 1,250 lb 1,200 hp Turbocharged Piston Engines | |

| Armament: | 12x Browning AN-M2 .50 Caliber MGs |

| Bombload: | 16,000 lbs |

| Cruise Speed: | 200 mph |

| Service Ceiling: | 32,000 ft |

| Range: | 2,300 mi |

10 May 1940

German Army Group A (GenObt K. R. Gerd von Rundstedt), consisting of the Fourth, Twelfth, and Sixteenth Armies, Army Group B (GenObt M A. F. F. Fedor von Bock), consisting of the Sixth and Eighteenth Armies, and Army Group C (GenObt Wilhelm J. F. Ritter von Leeb), consisting of the First and Seventh Armies, implement FALL GEIB (Case Yellow), invading the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, and France. They are joined by the Italian First (Gen Pietro Pintor) and Fourth Armies (Gen Alfredo Guzzoni) following a declaration of war on 10 June.

These invasions are shockingly effective and strong notice is taken of the German’s use of tactical airpower. Therefore, it is ironic that the Germans also launch the first major strategic bombing operation of the war during this period. With the advance stalling at Rotterdam, an opportunity is presented to surrender the city under threat of bombardment on 13 May. Poor communication results in the strike being launched the next day regardless, with 57 out of 100 He-111s dropping their loads before ground flares signal them to abort (the recall order was not heard). The wooden buildings of the city's medieval center are hit with incendiaries and the city burns uncontrollably. Responsibility of whom launched this strike, and its failure to heed recall, remains heavily contested. (884 killed)

With French resistance collapsing despite total commitment of their reserves, the British Expeditionary Force (FM Lord John S. S. P. Vereker) begins evacuations from Dunkirk on 26 May. French PM Paul Reynaud ultimately resigns on 16 June following a breakdown of cabinet support, with his successor, H. Philippe B. O. Pétain, signing an armistice of 21 June. Allied forces are now completely driven from the European continent.

15 May 1940

RAF BC launches this night 24 Armstrong Whitworth Whitleys, 36 Handley Page Hampdens, and 39 Vickers Wellingtons against a series of industrial targets in the German Ruhr valley, with the three largest forces amounting to nine aircraft each. German forces invaded France five days prior, the same day that the Rt. Hon. Winston L. Spencer-Churchill (CP) formally replaced the Rt. Hon. A. Neville Chamberlain (CP) as prime minister, and both political parties were in full agreement that limitations against strategic targets were to be lifted provided they be of a military nature. As such, this is the first strategic air operation against Germany in the Second World War. Taking into account additional minor operations against Belgium, this is also the first RAF BC operation involving more than 100 aircraft.

Accuracy is poor and a single civilian, Franz Romeike, is killed this night when, despite blackout conditions, he carries a light while walking to his outhouse.

| Bombers Launched: | 99 |

| Bombers Effective: | 81 |

| Bombers MIA: | 1 |

| Bombers Abort: | 8 |

| Abort Rate: | 8% |

| Loss Rate: | 1% |

| Aircraft Type | Serial No. | Code | Unit |

| Vickers Wellington Mk. IA | P9229 | S | 115 Squadron |

17 May 1940

RAF BC launches 24 Armstrong Whitworth Whitleys, 52 Vickers Wellingtons, and 54 Handley Page Hampdens against the railyards of Cologne and the oil refineries of Hamburg and Bremen, Germany. This if the first strategic air operation targeting Petroleum/Oil/Lubrication (POL) targets. No RAF BC aircraft are lost this night. (47 killed)

Like much of Europe, Germany is incredibly dependent on foreign oil, and the appointment of PM the Rt. Hon. Winston L. Spencer-Churchill (CP) on 10 May 1940 signified a catastrophic blow in this regard. Churchill immediately halted all peace feelers with Germany, and with the British naval blockade now permanently in place, Germany could no longer depend on maritime oil imports. With the only real European producer of oil outside the Soviet Union being Romania, the natural result is strong support for pro-German factions in the Romanian government (who depose the king this September).

Even with Romania's aid, oil usage in occupied-Europe is so tight that this month sees Generalbevollmächtigten für das Kraftfahrwesen (General Plenipotentiary for Motor Transport) Adolf von Schell seriously suggest a partial demotorization of the German military – even though only 30 of Germany’s 151 divisions in the east are motorized units! With a total fuel rationing program already in place, an inability to secure peace with Britain, and a year's fuel reserves remaining, German Führer Adolf Hitler pushes plans for an invasion of the Soviet Union to begin the following year in the hopes of quickly securing Russia’s oil centers.

British Air Ministry observers noted these developments early-on and long pushed for a sustained bombing campaign against Germany’s precious synthetic oil plants. Using processes developed by Friedrich K. R. Bergius, Franz J. E. Fischer, and Hans Tropsch, these plants produce synthetic oil using coal and are Germany's only real domestic producer of the substance. Despite the soundness of such a campaign, fickle demands from the Air Ministry prevent the RAF from continuing a sustained offensive against German oil refineries. In truth this makes sense, as RAF BC is incapable of the precision necessary to seriously affect German oil production at this point in the war.

21 June 1940

Avro Anson N9945 of the Blind Approach Training and Development Unit (BATDU) locates a narrow 31.5 MC German radio beam transmitting over Great Britain. Following the course of the beam, the crew discovers that a second beam intersects with the first directly over the Rolls-Royce plant in Derby. The so-called “Battle of the Beams” begins.

Interrogation of captured bomber crews throughout the previous months relayed the existence of a pair of navigation systems, KNICKEBEIN and X-Gerät, and wreckage revealed that German Lorenz receivers were far more sensitive than necessary for landing approaches. Convinced that Lorenz had been adapted into a blind-bombing system, Assistant Director of Intelligence (Science) Reginald V. Jones lobbied – with much resistance from the scientific community – for further research into the matter. This night’s events prove that Jones is correct.

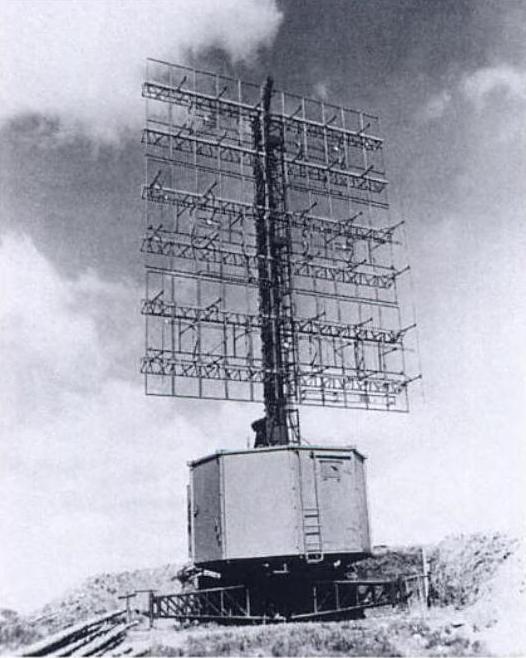

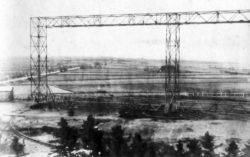

N9945 had, in fact, discovered a pair of KNICKEBEIN (Crooked Leg) beams, now code-named HEADACHE by the RAF. The system worked thusly: a pair of 100 ft antenna arrays, mounted on 315 ft semi-circle tracks, transmit a Lorenz-type signal over England. The bomber follows one of the beams, just as he would in landing, releasing his bombs once the second signal is intercepted, indicating where the beams "crossed." Three large KNICKEBEIN antennas were built throughout 1939 at the extreme edges of Germany - Kleve, Stollberg (Frisia), and Maulburg – and an additional nine, smaller units (102 ft semi-circle) were added throughout occupied France, Norway, and the Netherlands the following year.

Responsibility for jamming KNICKEBEIN is given to Robert Cockburn of the Telecommunications Research Establishment (TRE), with a special radio countermeasures unit (RCM), 80 Wing, being formed under Wg Cdr Edward B. Addison to implement their research. The effort is appropriately code-named ASPIRIN. Hospital diathermy sets are altered to operate on the 30-35 MC range and, following nightly BATDU patrols to locate the KNICKBEIN beams, sets are distributed along their paths, moderately jamming the signal. This is aided by a previously unrelated system where false navigation beacons, called “meacons,” are activated each night in the hopes of negating the possibility of beacons set-up by German agents.

| Station: | Location: | |

| K-1 | Klepp, Norway | |

| K-2 | Stollberg (Frisia), Germany | |

| K-3 | Julianadorp, the Netherlands | |

| K-4 | Kleve, Germany | |

| K-5 | Bergen op Zoom, the Netherlands | |

| K-6 | Mont Violette (Verlincthun), France | |

| K-7 | Greny (modern Petit-Caux), France | |

| K-8 | Mont Pinçon, France | |

| K-9 | Beaumont-Hague (modern La Hauge), France | |

| K-10 | Sortosville-en-Beaumont, France | |

| K-11 | Saint-Fiacre (Plestin-les-Grèves), France | |

| K-12 | Maulburg, Germany | |

| K-13 | Noto, Sicily |

1 July 1940

USAAF Chief of the Armament Laboratory (Materiel) LTC Grandison Gardner and Chief of Research and Development (Engineering) MAJ Franklin O. Carroll file a report entitled “Report on Trip Abroad,” covering powered gun turret development in Italy, France, and Great Britain. Part of a series of early-war observation reports which drastically alter USAAF thinking, the Gardner-Carroll report lauds turret development in the UK, arguing for a similar program covering all four axis points of US bomber aircraft. The reports spurs powered gun turret development in the US, a topic that, until this point, had been low priority.

Unfortunately, development of a forward facing turret receives little attention. Tests at Wright Field using a Curtiss P-36 against a Martin B-10 earlier that year suggested that forward-facing powered turrets were not a necessity. MAJ Richard C. Coupland concluded:

It is theoretically possible to attack a bombardment airplane from any angle . . . [but] the practical difficulties involved and the loss of effectiveness in any zone, except that of circumscribed by a 20° to 30° angle from the line of flight of the objective airplane, place such attacks in the category of a threat rather than an effective method of employing fire power.

13 August 1940

The Luftwaffe launches 74 Do-17s, 140 Ju-87s, and 96 Ju-88s, escorted by the 173 Bf-109s and 120 Bf-110s, against the RAE plant at Farnborough, the Westland plant at Yeovil, the ports of Sheerness and Portland, and the airfields of Andover, Boscombe Down, Eastchurch, Odiham, Warmwell, and Worthy Down, England. This is the first day of ADLERANGRIFF (EAGLE ATTACK), the campaign to achieve air superiority over the RAF prior to seaborne invasion, now scheduled for 15 September. Führer Adolf Hitler called for operations to begin on 1 August (Directive 17) but poor weather limited the Luftwaffe to a stream of minor operations. Poor weather fouls-up German plans this day as well.

Warned of incoming storms, RLM RM Hermann W. Göring personally issues a recall order which, because of a combination of incompetence and incompatible radios, is barely acknowledged. At first, poor RAF tracking of the formations hinders effective interception, but the German attack descends into a debacle when the launch order is finally given that afternoon. While the Luftwaffe is quick to realize that the Bf-110 is incapable of effective bomber escort – to the extent that they require escort themselves – intelligence fails to recognize that many of the airfields targeted are not, in fact, RAF FC stations. The Luftwaffe continues ADLERANGRIFF throughout the rest of August into early-September.

Prior to the war, the German military had little use for a purely strategic bomber, structuring its air force accordingly. As a financially-struggling land power, German strategy was army-centric, conducting quick campaigns with the other branches filling supporting roles. The failure to secure a peace with Great Britain complicated matters as neither the Luftwaffe or Kreigsmarine were up to the task of an island invasion. This is particularly apparent in the relatively short range of Germany’s medium bombers, leaving the Luftwaffe incapable of any serious campaign against Britain’s aircraft industry. The only air superiority they could theoretically achieve was by targeting airfields - hence the focus of the majority of ADLERANGRIFF's bombing operations.

Colloquially known as “potholing,” airfield strikes were infamously ineffective due to ease of runway repair. The Luftwaffe seems to have acknowledged this, as more emphasis is made toward ADLERANGRIFF's fighter component than any attempt to create a coherent bombing strategy. This too was a mistake. Purposely avoiding the targeting of radar installations, Luftwaffe strategists hoped that, by encouraging fighter interception, German fighters could force decisive battle with the RAF. The problem is that the only effective German fighter at this time, the Bf-109, lacks the range to stay over Britain for more than 30 mins (at most). The ultimate result is heavy losses of unescorted medium bombers, the majority of which are shot down after their escorts turn for home. While the Luftwaffe does indeed make some headway throughout ADLERANGRIFF, it does so at a heavy cost, never coming close to the decisive impact originally hoped for.

This night also sees 21 He-111s of KG100, a specialist unit, bomb the Castle Bromwich Aircraft Factory near Birmingham, England. This is the first operational use of the X-Gerät blind-bombing system. (7 killed)

| Bombers Launched: | 310 |

| Fighters Launched: | 293 |

| Bombers MIA: | 32 |

| Fighters MIA: | 15 |

| Loss Rate: | 10% |

| E/A Destroyed: | 13 |

| Aircraft Type | Serial No. | Pilot | Code | Unit |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | P3972 | Flt Lt Thomas F. Dalton-Morgan | unk | 43 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | R4102 | Plt Off C. Anthony Woods-Scawen | unk | 43 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | R4093 | Sgt Peter Hillwood | P | 56 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | N2429 | Fg Off Peter F. M.Davies | T | 56 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | P3479 | Plt Off Charles C. O. Joubert | unk | 56 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | P3587 | Fg Off Richard E. P.Brooker | unk | 56 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | P3387 | Fg Off Richard L. Glyde | unk | 87 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | P3348 | Sgt Philip P. Norris | B | 213 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | P3764 | Sgt Eric W. Seabourne | unk | 238 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | P3177 | Sgt Henry J Marsh | unk | 238 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | P3805 | Sgt Ronald Little | unk | 238 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | P2690 | Plt Off Howard C. Mayers | unk | 601 Squadron |

| Supermarine Spitfire Mk. I | N3091 | Flt Lt Stanislaw Brzezina | unk | 74 Squadron |

18 August 1940

The Luftwaffe launches 94 Do-17s, 111 He-111s, 109 Ju-87s, and 12 Ju-88s, escorted by 407 Bf-109s and 40 Bf-110s, against the airfields of Biggin Hill, Ford, Gosport, Hornchurch, Kenley, North Weld, and Thorney Island, as well as the radar station of Poling, England. The largest confrontation of the Battle of Britain, this day is later immortalized as ‘the Hardest Day.’

Rather than dispersing strikes, CG Luftflotte 2 GenFM Albert Kesselring recommended focusing on a small number of RAF airfields, launching disproportionately large numbers of escort fighters to wither down RAF interceptor numbers, which they believed were already close to exhaustion. More than anything, this was a result of poor intelligence, as while RAF FC is struggling to keep up its number of experienced pilots, aircraft manufacturers are at peak production and large numbers of new pilots are already being assigned to units in the north. Likewise, many of the airfields targeted this day (Ford, Gosport, and Thorney Island) are not FC installations at all - a common mistake made throughout the Battle of Britain.

A rather more horrific mistake occurs when poor timing results in the majority of Ju-87s reaching their targets without escort. Painfully slow, the dive bombers suffer massive losses, resulting in the type being withdrawn from further major operations over Britain. Another disaster occurs when, due to weather delays, a special low-level Do-17 attack on Kenley arrives well-ahead of the other forces. Due to the heavy losses of this strike (four out of nine), low-level operations are also abandoned after this day.

Dissatisfied with the performance of his fighter units, RLM RM Hermann W. Göring makes several significant changes after this day. First, he relieves a series of command officers deemed out-of-touch, hastily promoting accomplished fighter pilots like Werner Mölders (age 27) and Adolf J. F. Galland (age 28) to senior positions. This change results in no significant improvement other than a greater outspokenness from subordinates. One particular exchange between Galland and Göring becomes legendary within the Luftwaffe:

The theme of fighter protection was chewed over again and again. Goering clearly represented the point of view of the bombers and demanded close and rigid protection. The bomber, he said, was more important than record bag figures. I tried to point out that the Me-109 was superior in the attack and not so suitable for purely defensive purposes as the Spitfire, which, although a little slower, was much more maneuverable. He rejected my objection. We received many more harsh words. Finally, as his time ran short, he grew more amiable and asked what were the requirements for our squadrons. Mölders asked for a series of Me-109's with more powerful engines. The request was granted. "And you ?" Goering turned to me. I did not hesitate long. "I should like an outfit of Spitfires for my group." After blurting this out, I had rather a shock, for it was not really meant that way. Of course, fundamentally I preferred our Me-109 to the Spitfire, but I was unbelievably vexed at the lack of understanding and the stubbornness with which the command gave us orders we could not execute – or only incompletely – as a result of many shortcomings for which we were not to blame. Such brazen-faced impudence made even Göring speechless. He stamped off, growling as he went

More important, however, is the transfer of the majority of fighter units to Luftflotte 2, limiting the other air component of Germany's campaign against Britain, Luftflotte 3, to night operations. This move later proves disastrous.

| Bombers Launched: | 326 |

| Fighters Launched: | 447 |

| Bombers MIA: | unk |

| Fighters MIA: | unk |

| Loss Rate: | 9% |

| E/A Destroyed: | 28 |

| Aircraft Type | Serial No. | Pilot | Code | Unit |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | L1921 | Plt Off Neville D. Solomon | unk | 17 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | N2461 | Sqn Ldr Michael N. Crossley | F | 32 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | P3147 | Plt Off John F. Pain | unk | 32 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | R4106 | Sgt Leonard H. B. Pearce | unk | 32 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | V6535 | Plt Off Count R. C. G. H. de Grunne | unk | 32 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | V7363 | Flt Lt Humphrey a'B. Russell | unk | 32 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | P2923 | Fg Off Richard H. A. Lee | R | 85 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | N2340 | Sgt Albert H. Deacon | unk | 111 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | P3943 | Sgt Harry S. Newton | unk | 111 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | R4187 | Flt Lt Stanley D. P. Connors | unk | 111 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | P3940 | Sqn Ldr John A. G. Gordon | unk | 151 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | R4181 | Plt Off John B. Ramsay | unk | 151 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | P3708 | Sgt Alexander G. Girdwood | unk | 257 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | P3059 | Fg Off Kenneth N. T. Lee | D | 501 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | P3208 | Plt Off John W. Bland | T | 501 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | N2617 | Sgt Donald A. S. McKay | unk | 501 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | P2549 | Flt Lt George E. B. Stoney | unk | 501 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | P3815 | Plt Off Franciszek Kozlowski | unk | 501 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | R4219 | Plt Off Robert C. Dafforn | unk | 501 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | L1990 | Sgt Redvers P. Hawkings | unk | 601 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | R4191 | Sgt Leonard N. Guy | unk | 601 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | V7249 | Fg Off John A. Hemingway | unk | 601 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | P2768 | Sgt Peter K. Walley | unk | 615 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | P2966 | Flt Lt L. M. Elmer Gaunce | unk | 615 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | R4221 | Fg Off Petrus H. Hugo | unk | 615 Squadron |

| Supermarine Spitfire Mk. I | R6713 | Fg Off Franciszek Gruszka | unk | 65 Squadron |

| Supermarine Spitfire Mk. I | N3040 | Sqn Ldr R. Robert S. Tuck | unk | 92 Squadron |

| Supermarine Spitfire Mk. I | L1019 | Sgt Basil E. P. Whall | G | 602 Squadron |

25 August 1940

As a response to the mistaken German attack against London (which was off-limits) the previous night, RAF BC launches this night 22 Armstrong Whitworth Whitleys, 21 Vickers Wellingtons, and 46 Handley Page Hampdens against Berlin, Germany. This is the first deliberate RAF strike against the German capital. The operation goes poorly, with cloud cover too thick for the bombers to properly sight their assigned targets (the Klingenberg and Siemens power plants). As a result, the only bombs which fall within city limits destroy a garden house in the Pankow area of Berlin. Worse, due to the city being at the extreme edge of the Hampden's range, all of this night's losses are Hampdens suffering fuel exhaustion.

Regardless of these failures, the raid dramatically shakes confidence in the local government. Mere days earlier RLM RM Hermann W. Göring waved questions about a possible British retaliation by telling people not to take shelter at the sound of an air raid siren, but at the sound of AAA batteries opening fire. While Berlin's AAA defenses were indeed considerable, the inexperience of the gun crews result in their failure to down a single British aircraft. Still, the fallout of this crisis-of-confidence does not go so far as to break public will, the equally inexperienced bomber crews failing to impress with their poor accuracy - when news reports note that the majority of British bombs hit government-owned farmland to south, jokes arose that the British were "trying to starve us out."

| Bombers Launched: | 89 |

| Bombers Effective: | 13 |

| Bombers MIA: | 5 |

| Bombers Abort: | 76 |

| Abort Rate: | 85% |

| Loss Rate: | 7% |

| Aircraft Type | Serial No. | Code | Unit |

| Handley Page Hampden Mk. I | P4416 | L | 49 Squadron |

| Handley Page Hampden Mk. I | P2124 | R | 50 Squadron |

| Handley Page Hampden Mk. I | P2070 | X | 50 Squadron |

| Handley Page Hampden Mk. I | P1354 | Y | 83 Squadron |

| Handley Page Hampden Mk. I | P4380 | Z | 83 Squadron |

7 September 1940

As per Operation Loge (named for the Norse god of fire), the Luftwaffe launches some 328 bombers, escorted by 617 fighters, against London, England. This is the beginning of the German campaign against British urban targets, otherwise known as ‘the Blitz.’

In reaction to RAF BC strikes which began on 25 August against Berlin and other major cities, German Führer Adolf Hitler officially lifted the ban against bombing London on 30 August. This change in policy was previously championed by CG Luftflotte 2 GenFM Albert Kesselring, who felt that such a campaign might force the RAF into large-scale combat. Lacking the range to bomb targets throughout the entirety of England, Kesselring felt that the airfield bombing campaign was ineffectual. This was in stark contrast to CG Luftflotte 3 GenFM Hugo Sperrle, who advocated continuing the airfield campaign, convinced that German victory claims were a poor indicator of the RAF’s current strength.

Publicly embarrassed by the recent bombings and the Luftwaffe’s seeming inability to prevent them, RLM RM Hermann W. Göring endorsed Kesselring’s proposal. In truth, this was an act of some desperation, as the failure to achieve air superiority throughout August saw Hitler postpone the invasion date to 21 September – if Britain was to be invaded at all, the landings had to be made before October. Hitler announced the beginning of the urban campaign on 4 September at the opening of the annual Winterhilfswerk program at the Berlin Sportpalast.

Click here to read a transcription of Hitler’s speech at the Berlin Sportpalast.

The opening of the Blitz comes as a surprise to RAF controllers and the interceptions are somewhat delayed. This is particularly apparent in the units of 12 Group under AVM Trafford Leigh-Mallory. Up until this point, the bulk of the fighting was done by AVM Keith R. Park’s 11 Group, who covered the whole of southeast England. Park and Leigh-Mallory hotly disagreed as to interception methods, with Park advocating immediate interceptions while Leigh-Mallory advocated attacking in large groups even if it meant catching the Germans after they had dropped their loads. This day sees the first use of Leigh-Mallory’s “Big Wing” theory. Due to the inevitable delays caused by the forming of units after take-off, few aircraft of 12 Group see combat this day.

| Bombers Launched: | ≈328 |

| Fighters Launched: | ≈617 |

| Bombers MIA: | 14 |

| Fighters MIA: | 23 |

| Loss Rate: | 4% |

| E/A Destroyed: | 23 |

| Aircraft Type | Serial No. | Pilot | Code | Unit |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | V6641 | Sqn Ldr Caesar B. Hull | unk | 43 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | V7257 | Flt Lt Richard C. Reynell | unk | 43 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | V7309 | Sgt Alan L. M. Deller | unk | 43 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | P3234 | Flt Lt Reginald E. Lovett | unk | 73 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | P3025 | Sgt Thomas Y. Wallace | unk | 111 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | P2962 | Plt Off John Benzie | unk | 242 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | N2440 | Sgt John M. B. Beard | unk | 249 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | P3594 | Plt Off Pat H. V. Wells | unk | 249 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | R4114 | Plt Off Robert D. S. Fleming | unk | 249 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | R4230 | Sgt Frederick W. Killingback | unk | 249 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | P3049 | Flt Lt Hugh R. A. Beresford | unk | 257 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | V7254 | Fg Off Lancelot R. G. Mitchell | unk | 257 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | P3890 | PPor Jan K. M. Daszewski | unk | 303 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | R4173 | Por Marian Pisarek | unk | 303 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | V7437 | Nadrotmistr Josef Koukal | unk | 310 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | L1615 | Fg Off Kennth V. Wendel | unk | 504 Squadron |

| Supermarine Spitfire Mk. I | P9340 | Sgt John McAdam | unk | 41 Squadron |

| Supermarine Spitfire Mk. I | R6901 | Plt Off Walenty Krepski | unk | 54 Squadron |

| Supermarine Spitfire Mk. I | P9466 | Sqn Ldr Joseph S. O'Brien | unk | 234 Squadron |

| Supermarine Spitfire Mk. I | X4009 | Flt Lt Patrick C. Hughes | unk | 234 Squadron |

| Supermarine Spitfire Mk. I | N3198 | Fg Off William H. Coverley | unk | 602 Squadron |

| Supermarine Spitfire Mk. I | X4256 | Plt Off Henry W. Moody | unk | 602 Squadron |

| Supermarine Spitfire Mk. I | P9467 | Sgt Alfred R. Sarre | unk | 603 Squadron |

15 September 1940

The Luftwaffe launches 87 Do-17s and 52 He-111s, escorted by some 416 Bf-109s and 40 Bf-110s, against London, England. The events of this day are later commemorated via national holiday in Canada and Great Britain. With ground controllers fully prepared and lacking any diversionary strikes, this day sees 12 Group's "Big Wing" see action for the first time. While its success is far overstated in victory claims (to the point of ridiculousness) the sight of massed formations of British fighters nevertheless deals a heavy blow, causing a crisis-of-confidence in German high command with the realization that their previous counter-air campaign had, in fact, failed.

Frustrated with the Luftwaffe’s lack of progress and the RAF's continuing bombardment of invasion barges, German Führer Adolf Hitler calls off Operation SEELŐWE (SEA LION) – the invasion of Great Britain – on 17 September, indefinitely postponing it. Due to protests by RLM CS GenObt Hans Jeschonnek (RLM RM Hermann W. Göring is in France), Hitler concedes to allowing the Luftwaffe to continue its urban campaign. It is hoped that the surrender of the Soviet Union (whose invasion is currently being planned) might eventually force Britain to accept Germany's peace terms.

| Bombers Launched: | 139 |

| Fighters Launched: | ≤456 |

| Bombers MIA: | 27 |

| Fighters MIA: | 21 |

| Loss Rate: | 6% |

| E/A Destroyed: | 28 |

| Aircraft Type | Serial No. | Pilot | Code | Unit |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | P3080 | Fg Off Arthur D. Nesbitt | C | 1 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | P3876 | Fg Off Ross Smither | unk | 1 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | P3865 | Plt Off Roy A. Marchand | unk | 73 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | P3113 | Sgt Reginald T. Llewellyn | F | 213 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | N2537 | Plt Off Georges L. J. Doutrepont | unk | 229 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | V6616 | Plt Off Robert R. Smith | unk | 229 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | P2836 | Sgt Leslie Pidd | unk | 238 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | P2884 | Flt Lt George Ff. Powell-Shedden | unk | 242 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | P2954 | Kpt Tadeusz P. Chlopik | E | 302 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | P3577 | MłChor Michal Brzezowski | E | 303 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | P3939 | MłChor Tadeusz Andruszków | M | 303 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | R4085 | Major Alexander Hess | unk | 310 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | R4087 | Nadrotmistr Josef Hubacek | unk | 310 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | P2725 | Sgt Ray T. Holmes | unk | 501 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | P2760 | Plt Off Albert Hove d'Ertsenrijck | unk | 501 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | N2481 | Plt Off John V. Gurteen | unk | 504 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | N2705 | Fg Off Michael Jebb | unk | 504 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | L2012 | Plt Off T. P. Michael Cooper-Slipper | unk | 605 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | L2122 | Plt Off Robert E. Jones | unk | 605 Squadron |

| Hawker Hurricane Mk. I | V6688 | Plt Off Patrick J. T. Stephenson | unk | 607 Squadron |

| Supermarine Spitfire Mk. I | P9431 | Sgt Henry A. C. Roden | unk | 19 Squadron |

| Supermarine Spitfire Mk. I | X4070 | Sgt John A. Potter | unk | 19 Squadron |

| Supermarine Spitfire Mk. I | P9324 | Plt Off Gerald A. Langley | unk | 41 Squadron |

| Supermarine Spitfire Mk. I | unk | Plt Off Robert H. Holland | unk | 92 Squadron |

| Supermarine Spitfire Mk. I | X4182 | Plt Off Ronald MacKay | unk | 234 Squadron |

| Supermarine Spitfire Mk. I | R7019 | Sqn Ldr George L. Denholm | unk | 603 Squadron |

| Supermarine Spitfire Mk. I | X4324 | Fg Off Arthur P. Pease | unk | 603 Squadron |

| Supermarine Spitfire Mk. I | R6690 | Plt Off Geoffrey N. Gaunt | A | 609 Squadron |

9 October 1940

Two He-111s of III/KG26 bomb the Crown Tube Works of Birmingham, England this night. This is the first operational use of the Y-Gerät (Y-Apparatus) blind bombing system.

While simple in concept, Y-Gerät is operationally the most complex of the three German blind-bombing systems. One of two beam "apparatuses" developed under WOUTAN (after the Norse god Odin for his single eye), Y-Gerät operates on only one beam. The bomber follows a 45 MC beam toward the target, relaying via radar transponder a signal back to the transmitter station. When the bomber is over the target, the transmitter station gives the signal to release. Since progress is monitored from the ground, Y-Gerät is limited to a single aircraft per station. Despite this handicap, III/KG26 continues trial strikes using Y-Gerät, training as a pathfinder force throughout the winter of 1940/1941.

25 October 1940

Air Chf Mshl Sir Charles F. A. Portal formally replaces Air Chf Mshl Sir Cyril L. N. Newall as CAS, with Air Mshl Sir Richard E. C. Peirse taking over as CINC RAF BC. In a disgusting display of political intrigue, the removal of Newall is the first of a series of sackings in RAF leadership. A month later, CINC RAF FC Air Mshl Sir Hugh C. T. Dowding is replaced by former DCAS Air Mshl W. Sholto Douglas, and on 27 December, CO 11 Group AVM Keith R. Park is replaced by former CO 12 Group AVM Trafford Leigh-Mallory.

These changes bear consideration. While Newall and Dowding were already due for retirement - both are nearly a decade older than their contemporaries - their sackings come on the heels of the RAF's greatest success. In truth, two cabals were at play. By no means a personable man, Dowding already had a poor relationship with MRAF Lord Hugh M. Trenchard that dated back to the Great War, and Trenchard, elderly but ever-present, consistently pushed for his removal (the success of FC in comparison to BC's poor performance did not help). Worse, Dowding sided with Park in the controversial "Big Wing" argument, coming to a head at an Air Ministry meeting on 17 October. Dowding and Park were subjected to a kangaroo-court presided over by Douglas, with Leigh-Mallory going so far as to bring celebrity ace Wg Cdr Douglas R. S. Bader as a character witness. Newall was supposedly ill at the time but it should be noted that he distanced himself from the issue while Douglas firmly sided with Leigh-Mallory.

Newall was under a great deal of stress and memos by Douglas helped spread rumors that Newall was too frail to continue. In reality, much of this stress was the result of Newall running afoul of Minister of Aircraft Production Lord W. Max Aitken. Already one of the richest men in the UK, Aitken was one of PM the Rt. Hon. Winston L. Spencer-Churchill's closest confidants and was generally held responsible for the increase in aircraft production throughout 1940. The degree to which Aitken was responsible for this is debatable, but his bombastic personality and political power made him a formidable enemy. Aitken's poor relationship with Newall reached a boiling point when Aitken came upon a series of memos critical of RAF command by Wg Cdr Edgar J. McCloughry (angry at being passed over for promotion) and brought them to the PM's attention.

Newall and Dowding's enemies found common cause with the release of the Salmond Report on 18 September. The Luftwaffe night-bombing campaign caught the RAF surprisingly unprepared and MRAF Sir John M. Salmond was ordered to investigate possible solutions. Meeting on 25 September, political leaders were outraged by Dowding's curt dismissal of the report's recommendations (many of which were, in fact, ridiculous). As such, Newall's relief is treated as a necessary step in the violent rush to reorganize RAF command, with Dowding being first and foremost on the list of those needing replacement. Political infighting had already labelled Newall as feeble and ineffectual and Dowding as close-minded, the RAF's lackluster response to the night raids throughout late-1940 being the final straw.

14 November 1940

As per Operation Mondscheinsonate (Moonlight Sonata), Luftflotte 3 launches 509 Do-17s, He-111s, and Ju-88s this night against Coventry, England while another 43 bombers fly diversions. The Coventry force is led by thirteen He-111s of KG100 using the X-Gerät blind-bombing system, dropping flares and incendiaries to provide aiming points for the following bombers. This is the first use of “Pathfinder” bombing tactics.

While the existence of X-Gerät (X-Apparatus) had long been known, understanding it well enough to counter proved difficult. Radio decryptions revealed that KG100 was the only unit equipped to use X-Gerät, and beam monitoring units discovered KNICKEBEIN-like beams on the 65-75 MC wavelength. This was enough information to at least set up a crude jamming system called BROMIDE. On 5 November, He-111 "6N-BH" (6811, KG100) crashed on the beach near Bridport after mistakenly following a ‘meacon’ at Templecombe. Examination of this aircraft’s equipment revealed that BROMIDE’s modulation, 1,500 cycles, was 500 cycles too low, and as such, was easily filtered by bomber crews. Unfortunately, interservice rivalry over the salvaging of said wreckage slowed recovery of the bomber's equipment to the extent that this deficiency is not known until after the raid on Coventry.

Unlike KNICKEBEIN, which used a pair of Lorenz-type beams, X-Gerät uses six. The elder beam system developed under WOUTAN, X-Gerät aims three beams at the target (two fine outer beams and a coarse primary beam), providing an ever-narrowing path for the bomber to follow. The other three serve as crossbeams, each indicating distance: 30 mi, 12 mi, and 3 mi. Upon crossing the second crossbeam, a dual timer is started, the second timer being activated after crossing the third crossbeam. When the timer hands coincide, the bombs are dropped.

The bombing of Coventry is the single most destructive Luftwaffe air operation against Great Britain. BROMIDE is ultimately updated to account for its misalignment and a new countermeasure, STARFISH, is also implemented on 2 December wherein decoy fires are lit to obfuscate German pathfinder operations. RAF FC’s lack of an efficient night fighter force is highly criticized following similar subsequent attacks, with CINC RAF FC Air Mshl Sir Hugh C. T. Dowding receiving much of the blame. (568 killed)

| Bombers Launched: | 552 |

| Bombers Effective: | 449 |

| Bombers MIA: | 1 |

| Bombers Abort: | 103 |

| Abort Rate: | 19% |

| Loss Rate: | ≥1% |

| Station: | Code: | Location: |

| X-1 | DONAU | Julianadorp, the Netherlands |

| X-2 | RHEIN | Cap Gris-Nez, France |

| X-3 | ODER | Cap Gris-Nez, France |

| X-4 | ELBE | Cap Gris-Nez, France |

| X-5 | WESER | Cap de la Hague, France |

| X-6 | SPREE | Cap de la Hague, France |

| X-7 | ISAR | Morlaix, France |

| X-8 | unk | La Feuillée, France |

19 November 1940

Luftflotte 2 and 3 launches 439 Do-17s, He-111s, and Ju-88s against Birmingham, England this night, with another 30 bombers conducting diversionary strikes against London. The operation is led by pathfinders of KG100 using X-Gerät. One of the bombers, Ju-88A “B3-YL” (2189, KG54), is shot down by Bristol Beaufighter “H for Harry” (R2098, 604 Squadron), crewed by Flt Lt John Cunningham and Sgt John R. Phillipson. Cunningham and Phillipson are the first airmen to down an enemy aircraft using airborne interception radar (AI). (450 killed)

While it would take time to train radar operators and develop more efficient radars than the crude Mk. IV used this night, AI ultimately becomes the final solution to night bomber interception. Still, CINC RAF FC Air Mshl Sir Hugh C. T. Dowding's dismissal of the Salmond report and its insistence on visual tactics, such as having day-fighters carry wing-mounted spotlights and follow ground-based searchlights, had not gone over well, his superiors demanding a response other than simply waiting for AI to enter service. As such, Dowding is dismissed on 24 November.

| Bombers Launched: | 469 |

| Bombers Effective: | 384 |

| Bombers MIA: | 5 |

| Bombers Abort: | 85 |

| Abort Rate: | 18% |

| Loss Rate: | 1% |

16 December 1940

As per Operation ABIGAIL-RACHEL, RAF BC launches this night 9 Bristol Blenheims, 35 Armstrong Whitworth Whitleys, 61 Vickers Wellingtons, and 29 Handley Page Hampdens against Mannheim, Germany. Launched in retaliation for the bloody Coventry raid a month prior, this operation mimics German tactics by having eight Wellingtons act as pathfinders while the strike force carries a mixed load of incendiaries and traditional explosives. Accuracy is poor this night due to the inaccuracy of the pathfinders. This is the first "area-bombing" operation of RAF BC. (34 killed)

| Bombers Launched: | 134 |

| Bombers Effective: | 82 |

| Bombers MIA: | 3 |

| Bombers Abort: | 52 |

| Abort Rate: | 61% |

| Loss Rate: | 2% |

| Aircraft Type | Serial No. | Code | Unit |

| Bristol Blenheim Mk. IV | T2039 | unk | 101 Squadron |

| Handley Page Hampden Mk. I | X3063 | unk | 49 Squadron |

| Handley Page Hampden Mk. I | X3128 | unk | 61 Squadron |